Collision with terrain

Robinson Helicopter Company R66 (helicopter), C-GAUA

Timmins (Victor M. Power) Airport, Ontario, 18 nm WNW

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

History of the flight

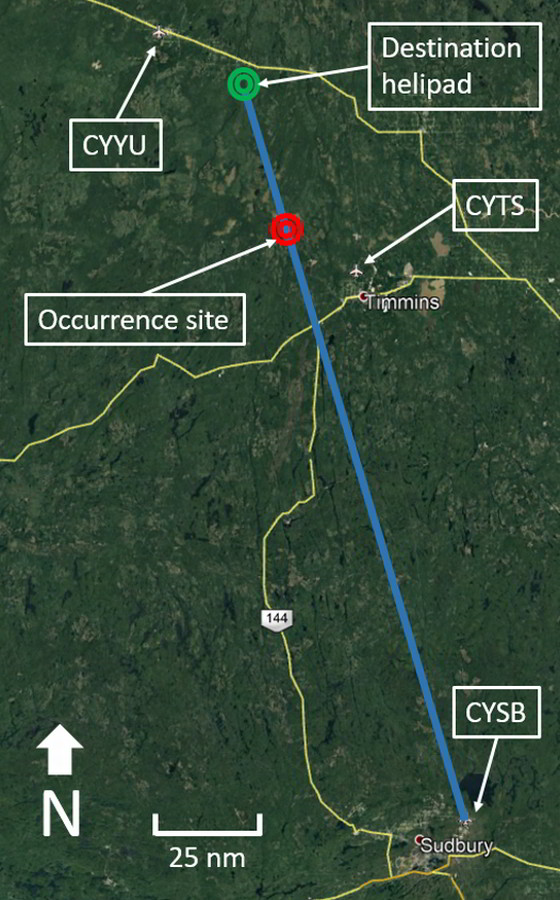

On 04 March 2019, the privately registered Robinson Helicopter Company R66 helicopter (registration C-GAUA, serial number 0142) departed Sudbury Airport (CYSB), Ontario, at 1842Footnote 1 on a visual flight rules (VFR) flight to a private helipad near Fauquier-Strickland, Ontario, with the pilot and 1 passenger on board. The helicopter collided with terrain at 2006, 36 nautical miles (nm) south-southeast of its destination (Figure 1).

On the day of the occurrence, the pilot had flown approximately 8 hours (air time) before the collision with terrain. The occurrence flight was the 4th flight of the day. The previous 3 flights were as follows:

- The 1st flight departed John C Tune Airport (KJWN), in Nashville, Tennessee, United States, at 0924, and landed at Springfield-Beckley Municipal Airport (KSGH), Ohio, United States, at 1156. The helicopter was then powered down for 40 minutes before the next departure.

- The 2nd flight departed KSGH at 1243 and landed at London Airport (CYXU), Ontario at 1448. The helicopter was then powered down for 1 hour and 14 minutes before the next departure.

- The 3rd flight departed CYXU at 1611 and landed at CYSB at 1821. The helicopter was then powered down for only 15 minutes before departing on the occurrence flight, at 1842.

Because evening civil twilight had ended at 1844, most of the occurrence flight was conducted under night VFR.

Although the aircraft was equipped with a transponder, it was not recorded on radar after leaving the Sudbury area.

Search efforts

On the morning of 06 March 2019, the police were notified of the overdue aircraft. A large-scale aerial search was initiated by the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre Trenton. Ground search efforts were organized by family and friends of the missing pilot and passenger.

In the afternoon of 11 March 2019, the wreckage was spotted from the air, approximately 18 nm west-northwest of Timmins (Victor M. Power) Airport (CYTS), Ontario, in a previously logged area of forest with deep snow coverage. Both occupants had been fatally injured. The helicopter was destroyed. There was no post-impact fire, and the emergency locator transmitter (ELT) did not activate.

Weather information

The investigation was unable to determine if or when the pilot reviewed weather information before the flight.

Graphical area forecast (GFA)Footnote 2 charts for the time period in which the occurrence flight took place forecasted broken ceilings at 4000 feet above sea level and localizedFootnote 3 reduced visibilities as low as 1½ statute miles (sm) in the destination area, which was approximately 20 nm east-southeast of Kapuskasing Airport (CYYU), Ontario.

The aerodrome forecasts (TAFs)Footnote 4 from CYYU and CYTS for the time of the occurrence flight were nearly identical, indicating light winds from the southwest, visibilities greater than 6 sm, and broken cloud at 4000 to 5000 feet above ground level (AGL). Between 1200 and 0300, a temporary condition (TEMPO)Footnote 5 of 5 sm visibility due to light snow showers with broken ceilings at 2000 feet AGL was forecast.

The weather radar from the weather radar site at Smooth Rock Falls, Ontario (located 30 nm east-southeast of CYYU), did not depict any significant snowfall for the duration of the occurrence flight.

An aviation routine weather report (METAR)Footnote 6 issued for CYTS at 2000 (6 minutes before the occurrence) reported visibility of 15 sm, with light snow showers and overcast cloud at 4000 feet AGL. The temperature was −16 °C. Previous METAR observations from CYTS indicated the presence of light snow showers beginning at 1453 on the day of the occurrence, with visibility as low as 1 sm (reported at 1746), nearly 1 hour before the occurrence flight departed from CYSB. A METAR observation for CYYU, located 53 nm north-northwest of the occurrence site, reported visibility as 2 sm, with light snow and overcast ceiling at 2000 feet AGL at the time of the occurrence, and had been reporting light snow as early as 1835.

Pilot information

The pilot held a Canadian private pilot licence – helicopter, a night rating, and a valid Category 1 medical certificate; he did not hold an instrument rating. The pilot had accumulated approximately 925 hours total flight time in helicopters, of which approximately 585 hours were flown in the occurrence helicopter. According to his personal log, in the 365 days before the date of the accident, the pilot had flown 157.5 hours, with 4.3 of those hours being flown at night. In that same time period, he had not conducted any night takeoffs, but had conducted 5 night landings, all of which took place more than 6 months before the occurrence flight.

To fly with passengers at night, a pilot is required to have completed 5 night takeoffs and 5 night landings in the previous 6 months.Footnote 7 The pilot had not conducted any night takeoffs or night landings in the 6 months before the occurrence flight and therefore did not meet the currency requirements to fly at night with a passenger on board.

Aircraft information

The Robinson Helicopter Company R66 is a 5-seat helicopter with a maximum gross weight of 1225 kg (2700 pounds). The pilot purchased the occurrence helicopter in January 2016. It was equipped with basic flight instruments—including an attitude indicator with inclinometer, heading indicator, altimeter, airspeed indicator, and turn coordinator—as well as engine instrumentation and an annunciator panel above the instrument cluster that displayed warning lights for various abnormal conditions. The helicopter was not certified to fly under instrument flight rules (IFR) and was not equipped with an autopilot. A portable GPS (global positioning system) device was mounted beside the instrument cluster and found at the accident site.

There were no pre-impact mechanical failures or system malfunctions identified that would have contributed to this accident.

The investigation determined that the engine was developing power and the rotor RPM was in the normal operating range at the time of the collision with terrain.

Accident site and aircraft wreckage information

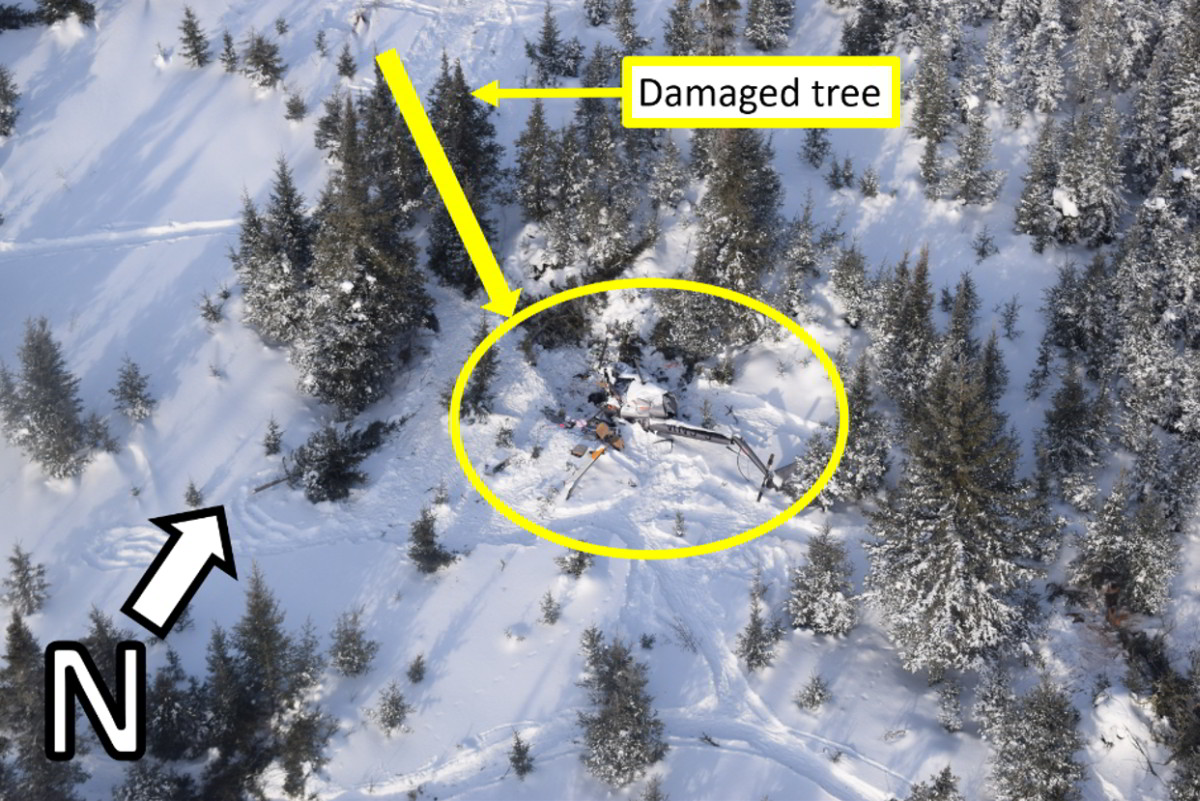

The collision with terrain occurred in an area that had been previously logged. The area had some sporadic regrowth, and the trees in the immediate vicinity of the accident site were approximately 6 m (20 feet) tall. The accident site was covered in at least 1.5 m (5 feet) of snow; a significant amount of snow had fallen during the week between the accident and the discovery of the wreckage.

There was tree damage at the top of a coniferous tree located approximately 10 m (33 feet) west-northwest of the impact site (Figure 2). The tree damage and the damage to the helicopter indicated that the aircraft was in a steep nose-down, left-bank attitude when it struck the ground, on an approximate heading of 120° magnetic.

The helicopter then pitched over and came to rest on its back. The tail boom had snapped at approximately the midpoint, and there was minor damage to the tail rotor. The main rotor blades were mostly buried in the snow, but showed significant damage when uncovered. All portions of the main rotor blades were still attached to the mast, which was partially separated from the helicopter. The gearbox and the engine (Rolls Royce RR-300) had broken free of their mounts. There was a strong odour of jet fuel at the site.

The flight instruments were examined to determine their readings at the time of impact; however, the only useful information obtained was from the airspeed indicator, which showed a reading of 107 knots at impact.

The occupants were ejected from the helicopter during the impact. There is no evidence that either occupant had been wearing a seatbelt at the time of the occurrence; however, given the damage to the helicopter, the accident was not survivable.

Emergency locator transmitter

During the impact sequence, the plastic mounting bracket for the 406 MHz ELT broke; however, the antenna and the remote switch wiring were still intact. The ELT was found in the OFF position; therefore, it did not activate during the crash or transmit a signal to the search-and-rescue satellite system. The pilot had removed the ELT in January 2019 for recertification and had picked it up from the avionics shop after the recertification was complete. The investigation could not determine who had re-installed the ELT. Because of the orientation of the ELT mounting bracket, the position of the switch cannot be seen once the ELT is installed in the helicopter.

Flight plan or flight itinerary

The Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs) state that the pilot of a VFR flight must file either a flight plan or flight itinerary for any flight that is conducted more than 25 nm from the departure airport.Footnote 8

A flight plan must include specific information about the aircraft and the flight, including the estimated time of departure, estimated time of arrival, and route of flight.Footnote 9 The flight plan must be filed with an air traffic control unit, a flight service station, or a community aerodrome radio stationFootnote 10 and will be opened automatically at the estimated time of departure. If the flight plan is not closed by the pilot, an air traffic control unit, a flight service station, or a community aerodrome radio station within 1 hour of the estimated time of arrival, a search for the missing aircraft will be initiated.Footnote 11

A flight itinerary contains the same information as a flight plan and must be left with the same agencies as with a flight plan, or with a responsible person chosen by the pilot.Footnote 12 The responsible person has to receive and acknowledge receipt of the itinerary, and is responsible for informing the proper authorities if the aircraft is overdue.

The pilot did not file a flight plan or flight itinerary for the occurrence flight. As a result, the occurrence helicopter was not reported overdue until the morning of 06 March 2019, over 36 hours after the occurrence.

Night visual flight rules

The occurrence flight took place at night over remote areas with almost no ambient or cultural sources of light from the ground. Illumination from the moon was negligibleFootnote 13 and the nearest major light source was the city of Timmins, which is 18 nm east-southeast of the accident site.

The Robinson R66 Pilot's Operating Handbook states the following regarding night VFR and what happens when outside visual reference is lost:

[the pilot] loses […] his ability to control the attitude of the helicopter. As helicopters are not inherently stable and have very high roll rates, the aircraft will quickly go out of control, resulting in a high velocity crash which is usually fatal.

Be sure you NEVER fly at night unless you have clear weather with unlimited or very high ceilings and plenty of celestial or ground lights for reference.Footnote 14

The principle behind VFR flight is that the pilot uses visual cues outside the aircraft (e.g., the horizon or ground references) to determine the attitude of the aircraft (position of the aircraft along the 3 principal axes of an aircraft—pitch, roll, and yaw—relative to the earth's horizon). Therefore, some basic requirements must be met when conducting VFR flight, whether it is during the day or at night.

Night flying over featureless terrain, such as bodies of water or remote wooded terrain, is particularly difficult. These conditions are commonly described in the aviation community as a black hole, which refers to not having visual reference to the ground due to the absence of lighting. Under these conditions, it can be difficult or impossible for a pilot to discern a horizon visually, potentially leading to spatial disorientation and loss of control.

According to CARs sections 602.114 and 602.115, an aircraft on a VFR flight must be “operated with visual reference to the surface,”Footnote 15,Footnote 16 regardless of whether it is operated in controlled or uncontrolled airspace. The CARs define surface as “any ground or water, including the frozen surface thereof.”Footnote 17 However, the CARs do not define “visual reference to the surface,” which has been widely interpreted by the industry to mean visual meteorological conditions.

Therefore, a flight conducted over an area away from cultural lighting and where there is inadequate ambient illumination to clearly discern a horizon would not likely meet the requirements for operation under VFR (i.e., to continue flight solely by reference to the surface). Instead, such flights would require pilots to rely on their flight instruments to ensure safe operation of the aircraft.

A TSB investigation reportFootnote 18 on a helicopter that crashed while departing under VFR at night from a remote airport with limited lighting raised the issue of a lack of clarity in the definition of what flight “with visual reference to the surface” means in practice. The Board recommended that

the Department of Transport amend the regulations to clearly define the visual references (including lighting considerations and/or alternate means) required to reduce the risks associated with night visual flight rules flight.

TSB Recommendation A16-08

At March 2019, Transport Canada (TC) had taken actions to address the safety deficiency identified in this recommendation, regarding a clear definition of the visual references required to reduce the risks associated with night VFR flight. More specifically, it carried out a pilot project to evaluate and develop appropriate conditions for the use of Night Vision Imaging Systems for night VFR operations, and drafted a proposed Special Authorization (SA) and associated Advisory Circular (AC), which expand on current definitions and introduce new definitions regarding VFR.

TC has also indicated that regulatory development is currently underway. According to its March 2019 response, TC anticipates that the proposed amendments to the CARs will be released for public consultation in 2019.

The Board is encouraged by TC's efforts to address Recommendation A16-08. The SA and AC enhance current definitions and introduce new definitions regarding VFR. However, as the regulatory development is currently underway, no details of the proposed amendments are yet available. Until the regulations are finalized, the Board is unable to determine to what extent these actions will address the safety deficiency identified in Recommendation A16-08.

Therefore, TC's response to Recommendation A16-08 remains as Satisfactory Intent.

Safety messages

Maintaining adequate visual reference to the ground is crucial to the safety of flight under night VFR. During flight over remote areas with little ambient or cultural ground-based lighting, the conditions whereby visual reference to the ground can be maintained will vary depending on the illumination provided by the moon, cloud cover, and light sources within the aircraft itself. Continued flight in the absence of the required visual references would require the flight to be conducted under IFR. When flying VFR at night, pilots can unexpectedly lose visual reference to the ground even in good weather.

Night currency regulations help ensure the safety of pilots and passengers onboard aircraft operating at night, and it is important for pilots to maintain their regulatory currency.

When planning any VFR flight, pilots should conduct a thorough review of the expected weather and its effects on their ability to maintain visual reference to the ground, taking into account their own level of ability.

Filing a flight plan or a flight itinerary with the appropriate agency or a responsible person increases the likelihood that an overdue aircraft will be reported in a timely manner, and may increase the chance of survival in the event of an accident.

In the event of an accident, an armed and functioning ELT is a key factor in alerting search and rescue services.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board of Canada's investigation into this occurrence. The Board authorized the release of this report on . It was officially released on .