Loss of control and collision with terrain

Privately registered

Mooney M20J, C-FLJL

Sundridge/South River Airpark, Ontario

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

History of the flight

On 16 September 2021, at approximately 1353,Footnote 1 the privately registered Mooney M20J aircraft (registration C-FLJL, serial number 24-1375) departed from Runway 15 at Toronto/Buttonville Municipal Airport (CYKZ), Ontario, for a visual flight rules (VFR) flight to Sundridge/South River Airpark (CPE6), Ontario, with 1 pilot and 1 passenger on board. The purpose of the flight was for both occupants to meet with members of The Ninety-Nines, Inc.Footnote 2 at CPE6, for the East Canada Section’s 2021 Gold Cup Air Rally.

After takeoff, the aircraft climbed to cruise altitude and established a north-northeast track toward CPE6. At approximately 1447, the aircraft flew over the aerodrome, and then turned to join the left downwind leg for the approach to Runway 30. Before the aircraft turned on final approach, it was travelling at an altitude of approximately 1900 feet above sea level (ASL) (450 feet above ground level [AGL]) and a ground speed of 70 knots. The aircraft then turned onto final approach for Runway 30.

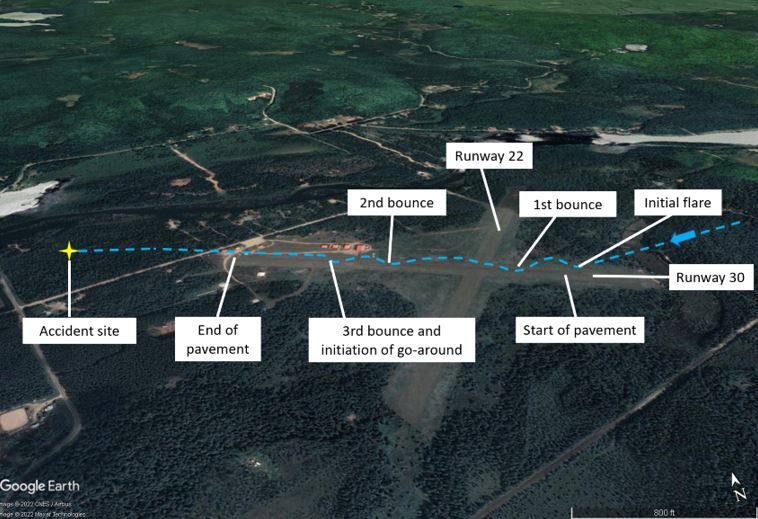

Observers who had aviation experience reported that during the latter stages of the final approach, the aircraft’s nose-down pitch attitude increased, and its airspeed and rate of descent were faster than a normal approach for a Mooney M20J aircraft. During the initial flare, the aircraft ballooned into the air and then bounced 3 times on the runway surface (Figure 1).

During the 2nd bounce, the aircraft landed on its nose wheel and wheelbarrowed momentarily before becoming airborne. During the 3rd bounce, it was reported that the aircraft bounced approximately 15 feet into the air and appeared to have lost a significant amount of airspeed and momentum. At this point, approximately 700 feet of the runway remained.

The pilot initiated a go-around after the 3rd bounce and retracted the landing gear. As the aircraft slowly climbed and cleared some smaller trees located approximately 250 feet from the departure end of the runway, it was reported to be moving slowly and not accelerating. The aircraft then disappeared from view and, shortly afterwards, crashed into a wooded area located approximately 1300 feet from the end of Runway 30.

At approximately 1451, eyewitnesses contacted emergency services, including the Joint Rescue Coordination Centre (JRCC), in Trenton, Ontario, to report the accident along with the approximate location. The aircraft’s 406 MHz emergency locator transmitter activated, and the signal was received by the JRCC. At 1455, the JRCC tasked a Royal Canadian Air Force CH-146 Griffon helicopter, which was already airborne and flying toward the region of Trois-Rivières, Quebec, with the search and rescue mission. The Griffon was diverted toward CPE6 and stopped for fuel en route. A Royal Canadian Air Force CC-130H Hercules based in Trenton, Ontario, was also tasked by the JRCC and departed at 1556. In addition, local first responders were dispatched and began conducting a ground search.

The CC-130H Hercules arrived overhead of the occurrence scene at 1630, followed by the Griffon helicopter at 1635 and the aircraft was located at approximately 1637. Both occupants were found wearing their safety belts with shoulder harnesses. The passenger was fatally injured. The pilot received critical injuries and was transported to hospital by air ambulance, but died before arrival at the hospital.

Accident site and aircraft wreckage

The on-site examination of the accident site determined that the right wing initially impacted a large tree and a large portion of the wing separated from the aircraft. The damage to the right wing leading edge indicated a slightly nose-up attitude with the wings nearly level. The aircraft subsequently rolled to the right and struck other trees before impacting the ground in an almost completely inverted position. There was no post-impact fire.

The aircraft systems were examined to the degree possible, and no indication of a malfunction was found. Damage to the propeller was consistent with power being produced at the time of impact, although the amount of power could not be determined. The throttle, mixture, and propeller controls were found in the full forward position. The magneto key was found in the LEFT position; however, the key sustained significant damage and was bent toward the LEFT position.Footnote 3

The landing gear was found in the up and locked position. The position of the stabilizer trim jack screw actuator indicated that the aircraft was trimmed in a take-off configuration. The flap actuator position indicated a full retraction of the flaps. It could not be determined whether the flaps had been selected down for the landing, or when, if at all, they had been selected back to the up position.

The fuel selector was found selected to the RIGHT tank. Both fuel tanks were compromised and the actual amount of fuel on board could not be measured. However, the investigation calculated that there were approximately 36 gallons of fuel on board at the time of the occurrence.

The aircraft’s engine was significantly damaged by the impact. It was disassembled and examined at the TSB's regional facility in Richmond Hill, Ontario. There were no signs of catastrophic engine failure. All of the internal components were complete and intact and showed no signs of abnormal wear.

No deficiencies were found with the mechanical fuel pump. The auxiliary electric pump was tested and determined to be functional; however, it could not be determined if it was selected to the ON or OFF position at the time of the occurrence.

During the examination of the engine, it was noticed that several of the ignition harness leads were worn and in very poor condition. There was damage to the outer insulation, woven copper shielding, and inner insulating layer. However, the centre conductors, which carry electrical power to the spark plugs, were undamaged. Electrical arcing was observed between the inner conductor and shielding at 3 locations during a post-occurrence high tension test. It was not possible to confirm if this arcing predated the accident given that the damage to the inner conductor appeared to be recent, likely the result of the accident sequence.

Engine cylinder head temperatures and exhaust gas temperatures for the occurrence flight were recovered from an on-board engine data monitoring unit, which had been set to record data once every 118 seconds. The temperature readings were consistent with normal engine operation at the time of the occurrence.

Data from the on-board GPS (global positioning system) were downloaded and analyzed. The data ended when the aircraft flew over CPE6; consequently, there were no GPS data for the rest of the occurrence flight, including the 3 bounces, the go-around, and the impact with terrain. Radar data from NAV CANADA were also analyzed. This data ended when the aircraft was on the base leg, before turning for the final approach. The aircraft instruments were also examined; however, no useful information pertaining to the occurrence was found.

Aerodrome information

CPE6 is located approximately 32 nautical miles south of North Bay Airport (CYYB), Ontario, and has an elevation of 1190 feet ASL. The aerodrome traffic frequency is a UNICOM (universal communications) on 122.8 MHz. The aerodrome has 2 runways. Runway 12/30 is an asphalt runway that is 2648 feet long and 40 feet wide with an additional 400 feet of grass before the beginning of asphalt on Runway 30. Runway 04/22 is a grass runway that is 3200 feet long and 150 feet wide. The terrain on the approach to Runway 30 slopes downward, and 1 nautical mile from the runway, the elevation is approximately 260 feet higher than the runway.

Weather information

The weather was suitable for the VFR flight. The hourly aerodrome routine meteorological report issued at 1500 for CYYB, the closest airport to the accident site, reported the winds from 190° true (T) at 8 knots, variable from 180°T to 270°T. Visibility was 30 statute miles. There were few clouds at 3500 feet AGL, with a temperature of 21 °C and a dew point of 10 °C. The altimeter setting was 30.21 inches of mercury.

The wind at CPE6 was reported as light and variable from the southwest.

Pilot information

The occurrence pilot held the appropriate licence for the flight in accordance with existing regulations. She had a private pilot licence — aeroplane, and her medical certificate was valid. She had accumulated approximately 3211 total flying hours and approximately 646 of those hours were on the occurrence aircraft. The pilot had also flown into CPE6 at least once previously.

The passenger, seated in the right-hand front seat, also held a private pilot licence — aeroplane.

Aircraft information

The Mooney M20J aircraft is a 4-seat, low-wing aircraft equipped with a fuel-injected Lycoming IO-360-A3B6D engine, a McCauley 2-blade constant-speed propeller, and electrically actuated retractable landing gear. The aircraft has dual flight controls and can be flown from either the left or the right seat.

The aircraft had accumulated approximately 3124 hours of total air time before the occurrence and had been owned by the occurrence pilot since November 2013. The last annual inspection was completed in June 2021.Footnote 4

According to the Pilot’s Operating Handbook and FAA Approved Airplane Flight Manual: Mooney M20J, the stall speed of the aircraft at its maximum certificated gross weight is 61 knots indicated airspeed (KIAS) with the landing gear and flaps up (flaps at 0°) and 54 KIAS with the landing gear and flaps fully down (flaps at 33°).Footnote 5

The manual also contains a section on normal procedures that includes the following procedure titled “Go Around (Balked Landing):”

- Power - FULL THROTTLE AND 2700 RPM.

- AIRSPEED - 65 KIAS.

- Flaps - AFTER CLIMB ESTABLISHED RETRACT TO 0 DEGREES WHILE ACCELERATING TO 73 KIAS.

- Gear - RETRACT AFTER CLIMB IS ESTABLISHED.

- Cowl flaps - FULL OPEN.Footnote 6

Weight and balance

The maximum certificated gross weight for the aircraft is 2740 pounds (1243 kg).Footnote 7 The investigation did not locate any documentation indicating a weight and balance calculation for the occurrence flight; however, weight and balance calculations completed by the TSB after the occurrence indicate that the aircraft’s weight was approximately 24 pounds under the maximum certificated gross weight at the time of takeoff from CYKZ and within the centre-of-gravity limitations at the time of the occurrence.

Aircraft maintenance and inspection requirements

Small privately operated Canadian aircraft must be inspected at intervals not exceeding 12 months. The inspection must be performed and recorded using a checklist that includes all items in Appendix B of the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs) Standard 625, and the applicable items in Appendix C. Appendix B, Part I, Scheduled Inspections for Small Aircraft other than Balloons, describes the mandatory inspection items for various parts of the aircraft. The following inspection items are included under the Engine and Nacelle Group:

(h) Lines, hoses and clamps – inspect for leaks, improper condition and looseness;

[…]

(k) All systems – inspect for improper installation, poor general condition, defects and insecure attachment […].Footnote 8

Under General Procedures, CARs Standard 625 Appendix B also states the following:

(4) The method of inspection for each item on the maintenance schedule shall be in accordance with the manufacturer’s recommendations or standard industry practice.

[…]

(5) The depth of inspection of each item on the schedule shall be determined by the person performing the inspection, and shall be consistent with the general condition and operating role of the aircraft.Footnote 9

An inspection of the ignition system is not explicitly described within the regulatory guidance on basic annual inspections for small aircraft, and there are no requirements to follow the manufacturer’s recommendations, except for the method of inspection. However, the Mooney M20J Service and Maintenance Manual recommends that ignition harnesses be checked “for condition, secure anchorage, loose terminals, and burned or chaffed insulation”Footnote 10 during annual inspections.

Unstable approaches, rejected landings, and go-around procedures

During the latter stages of the approach, when the aircraft’s nose-down pitch attitude reportedly increased, the aircraft’s rate of descent and airspeed likely increased as well, and the approach likely became unstable. However, the recorded data available to the investigation were insufficient to accurately determine the aircraft’s speed and rate of descent during the occurrence sequence. During the flare, the aircraft ballooned and bounced 3 times before a go-around was initiated.

Although the occurrence aircraft was observed slowly climbing over the smaller trees at the end of the runway before disappearing from view, the investigation was unable to determine whether the airspeed decreased below a safe flying speed, resulting in an aerodynamic stall, or whether the aircraft impacted the trees during the climbout, resulting in a loss of control and impact with the ground.

Often, landing accidents in general aviation are the result of a loss of control, usually in flight, but also on the ground following touchdown. As explained in Transport Canada’s Aviation Safety Letter, many landing accidents are a result of unstable approaches, or pilots not executing a timely go-around.Footnote 11

In March 2019, Transport Canada amended the Flight Test Guide - Private Pilot Licence - Aeroplane (TP 13723)Footnote 12 to include a stabilized approach for all approaches to a landing.

In the guide, a generic description of the stabilized approach criteria (VFR) is as follows:

On the correct final approach flight path:

- Briefings and checklists complete;

- Aircraft must be in the proper landing configuration appropriate for wind and runway conditions;

- Appropriate power settings applied;

- Maximum sink rate of 1,000 feet per minute;

- Speed within +10/-5 knots of the reference speed;

- Only small heading and pitch changes required;

- Stable by 200 feet AGL.

Note: If stability is not established by 200 feet AGL, an overshoot will be executed.Footnote 13

During a landing, if a pilot feels that the aircraft is descending faster than it should, a natural reaction may be to increase the pitch attitude and angle of attack too rapidly. This tendency not only stops the aircraft’s descent, but actually causes it to start climbing. Climbing during the initial round out is known as ballooning and increases the risk of entering an aerodynamic stall. If ballooning is excessive, the engine power should be applied for a go-around. Trying to salvage the landing increases the risk of the aircraft contacting the runway in an undesired attitude and causing it to bounce back into the air.

In addition, as stated in From the Ground Up, “[a] go-around can become a very risky flight procedure if the pilot does not decide soon enough that a go-around is the best choice and delays making a decision until the situation has become critical.”Footnote 14

During a go-around, as explained in the Airplane Flying Handbook, the management of the flaps is important because “a sudden and complete retraction of the flaps could cause a loss of lift resulting in the airplane settling into the ground.”Footnote 15

TSB laboratory reports

The TSB completed the following laboratory reports in support of this investigation:

- LP134/2021 – NVM Recovery

- LP140/2021 – Instrument Analysis

- LP141/2021 – Annunciator Lamps Analysis

- LP013/2022 – Ignition Harness Examination

Safety messages

Unstable approaches can lead to landing accidents. Pilots are reminded to conduct a go-around as soon as they recognize that an approach has become unstable.

The regulatory requirements for annual inspections of small private aircraft do not specify the depth of inspection that may be required for each item or for specific aircraft types. Aircraft owners and aircraft maintenance engineers should consult the manufacturer’s recommendations and consider the general condition and operating role of the aircraft when determining the depth of inspection required during the annual inspection.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s investigation into this occurrence. The Board authorized the release of this report on . It was officially released on .