Collision with terrain

Wilderness Seaplanes Ltd.

Grumman G-21A, C-GDDJ

Bella Bella (Campbell Island) Airport (CBBC), British Columbia, 0.5 NM SE

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

At 1428 Pacific Standard Time on 18 December 2023, the Wilderness Seaplanes Ltd. Grumman G-21A Goose aircraft (registration C-GDDJ, serial number 1184) departed Bella Bella (Campbell Island) Airport (CBBC), British Columbia, on a visual flight rules flight to Port Hardy Airport (CYZT), British Columbia, with 1 pilot and 4 passengers on board. Shortly after takeoff, the aircraft experienced a dual engine failure and was unable to maintain altitude. The pilot transmitted a Mayday call on the radio before the aircraft collided with terrain a short distance from the departure runway. The pilot and passengers were able to egress the aircraft and make their way to a nearby road, from which they were transported to hospital by motor vehicle. All occupants received minor injuries. The aircraft was substantially damaged.

1.0 Factual information

1.1 History of the flight

On 18 December 2023, the Wilderness Seaplanes Ltd. (Wilderness Seaplanes) Grumman G-21A Goose (Goose) aircraft was conducting a visual flight rules flight from Bella Bella (Campbell Island) Airport (CBBC),All locations mentioned in this report are in the province of British Columbia, unless otherwise noted. to Port Hardy Airport (CYZT), with 1 pilot and 4 passengers on board. This flight was the 3rd flight of the day for the aircraft and pilot. The 1st flight transported 5 passengers from CYZT to a fish farm at Kid Bay (52°47'57" N, 128°23'44" W). The 2nd flight was planned from Kid Bay to CYZT with 4 passengers on board. During that flight, weather conditions en route resulted in a diversion to CBBC where the aircraft was fuelled from a 40-gallon fuel drum before departing for CYZT.

During the water taxi into Kid Bay following the aircraft’s 1st flight, the landing gear was cycled as part of the docking procedure. When the landing gear was selected up, it did not retract electrically and had to be retracted manually using the hand crank. Following this gear cycle, and before departing Kid Bay, the malfunction of the primary landing gear retraction system was not recorded in the aircraft journey log and was not reported to dispatch or maintenance personnel for evaluation and rectification.

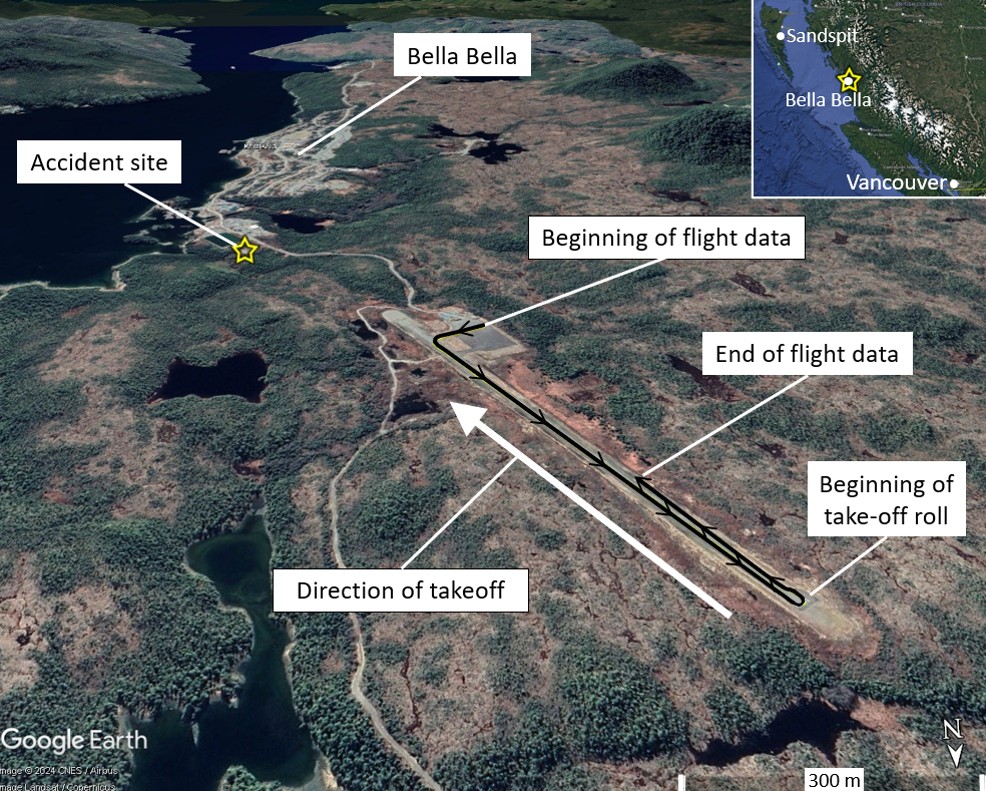

At 1428,All times are Pacific Standard Time (Coordinated Universal Time minus 8 hours). the aircraft departed Runway 13 at CBBC. Shortly after takeoff, while climbing through approximately 150 feet above ground level (AGL), the left engine surged and lost power. Seconds later, the right engine also lost power. The pilot transmitted a Mayday call on the aerodrome traffic frequency (ATF) and attempted to retract the landing gear, but there was insufficient time to do so using the manual system. The pilot performed a forced landing, and the aircraft came to rest in a forested area approximately 600 m from the departure threshold of the runway, and 130 m left of the extended centreline (Figure 1).

The aircraft was substantially damaged. The aircraft emergency locator transmitter (ELT) did not activate. There was no post-impact fire. The pilot and passengers received minor injuries. All occupants were able to egress the aircraft and walk to a nearby road where local residents transported them to hospital. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) attended the scene.

1.2 Injuries to persons

The pilot and 4 passengers were on board. Table 1 outlines the degree of injuries received.

Degree of injury | Crew | Passengers | Persons not on board the aircraft | Total by injury |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Fatal | 0 | 0 | – | 0 |

Serious | 0 | 0 | – | 0 |

Minor | 1 | 4 | – | 5 |

Total injured | 1 | 4 | – | 5 |

The pilot’s injuries were partially the result of the occupiable space within the cockpit being compromised, as the impact with terrain forced the cockpit floor upwards and rearwards. Passenger injuries were consistent with flailing or contact with the aircraft structure.

1.3 Damage to aircraft

The aircraft was substantially damaged as a result of the impact forces.

1.4 Other damage

Several trees were damaged when they were struck by the aircraft.

1.5 Personnel information

Pilot licence | Airline transport pilot licence - aeroplane |

|---|---|

Medical expiry date | 01 June 2024 |

Total flying hours | 9297 |

Flight hours on type | 1719 |

Flight hours in the 24 hours before the occurrence | 4.7 |

Flight hours in the 7 days before the occurrence | 8.4 |

Flight hours in the 30 days before the occurrence | 23.1 |

Flight hours in the 90 days before the occurrence | 90.1 |

Flight hours on type in the 90 days before the occurrence | 71.9 |

Hours on duty before the occurrence | 5.5 |

Hours off duty before the work period | 16.5 |

The pilot held the appropriate licence and ratings for the flight in accordance with existing regulations. He held an airline transport pilot licence – aeroplane for single- and multi-engine landplanes and seaplanes. He held a Group 1 instrument rating, and his Category 1 medical certificate was valid. His most recent pilot proficiency check on the occurrence aircraft type was on 08 December 2023.

At the time of the occurrence, the pilot had been working for Wilderness Seaplanes for approximately 6 years and held the position of chief pilot. He had accumulated approximately 3000 hours of flight time on float-equipped aircraft during that time and had become a Transport Canada (TC) approved check pilot (ACP) on the occurrence aircraft type approximately 3 weeks before the occurrence.

1.6 Aircraft information

Manufacturer | Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corp.* |

|---|---|

Type, model, and registration | G-21A, C-GDDJ |

Year of manufacture | 1942 |

Serial number | 1184 |

Certificate of airworthiness issue date | 12 September 2006 |

Total airframe time | 26 603.3 hours |

Engine type (number of engines) | Pratt & Whitney R-985 Wasp Junior (2) |

Propeller type (number of propellers) | Hartzell HC-B3R30-2E (2) |

Maximum allowable take-off weight | 9200 lb (4173.1 kg) |

Recommended fuel types | 80/87, 100LL |

Fuel type used | 100LL |

* The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is currently the custodian of the aircraft type certificate for this aircraft type.

1.6.1 General

The Goose is an all-metal, twin-engine, high-wing, amphibious aircraft powered by 2 Pratt & Whitney R-985 Wasp Junior radial engines. A total of 345 Goose aircraft, including all military variants, were manufactured.Geoff Goodall’s Aviation History Site, Grumman G-21/JRF/OA-9 Goose (10 February 2020), p. 1, at https://www.goodall.com.au/grumman-amphibians/grummangoose.pdf (last accessed on 06 November 2025). At the time of the investigation, 4 of these aircraft were registered in Canada.Transport Canada, Canadian Civil Aircraft Register, at https://wwwapps.tc.gc.ca/Saf-Sec-Sur/2/CCARCS-RIACC/RchSimpRes.aspx?cn=%7c%7c&mn=G21A%7c&sn=%7c%7c&on=%7c%7c&m=%7c%7c&rfr=RchSimp.aspx (last accessed on 06 November 2025). The occurrence aircraft (Figure 2) was manufactured in the United States in 1942 and was flown by the U.S. Navy until 1955.Geoff Goodall’s Aviation History Site, Grumman G-21/JRF/OA-9 Goose (10 February 2020), p. 34, at https://www.goodall.com.au/grumman-amphibians/grummangoose.pdf (last accessed on 06 November 2025). It subsequently flew under U.S. civil registration until the aircraft was imported to Canada in 1998.Transport Canada, Canadian Civil Aircraft Register, at https://wwwapps.tc.gc.ca/Saf-Sec-Sur/2/CCARCS-RIACC/ADet.aspx?id=16138&rfr=RchSimp.aspx (last accessed 06 November 2025).

The aircraft’s weight and centre of gravity at the time of departure were within the prescribed limits.

1.6.2 Maintenance

The most recent aircraft maintenance—the replacement of the dual tachometer indicator due to an unserviceable right tachometer—was performed approximately 3.3 hours before the accident.

At the time of the occurrence, the aircraft was being operated with an inoperative electrical landing gear retraction system. An alternate system was available to retract the aircraft landing gear; however, this backup system retracted the landing gear at a slower rate and required manual operation by the pilot. According to the Goose flight manual, a complete landing gear cycle using the hand crank takes approximately 39 turns of the handle.Pacific Coastal Airlines, Grumman G-21A “Goose” Flight Manual, Revision #2 (05 November 2008), section 2.6.2: Landing Gear, p. 2.9.

The investigation examined maintenance records for the occurrence aircraft dating back to the beginning of 2021 and found 1 instance where the landing gear selector handle was documented as stiff, and 1 instance where the landing gear up microswitch was found slightly out of adjustment. In both cases, the defect was documented, and maintenance was performed to return the aircraft to service.

1.6.3 Recording aircraft defects

Wilderness Seaplanes’ Company Operations Manual requires that pilots record defects in the aircraft journey log at the earliest opportunity after discovery and advise both dispatch and maintenance so that maintenance personnel can determine if a defect may be deferred, or if it must be rectified before flight.Wilderness Seaplanes Ltd., Company Operations Manual, Amendment #6 (06 June 2021), section 3.10.4: Aircraft Defects, p. 3-22.

The Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs) require the pilot-in-command of an aircraft to record “[p]articulars of any defect in any part of the aircraft or its equipment that becomes apparent during flight operations”Transport Canada, SOR/96–433, Canadian Aviation Regulations, Subpart 605, schedule I, item 9. in the aircraft journey log.

The occurrence pilot did not record the electrical landing gear retraction system defect in the aircraft journey log, and he did not report it to company dispatch or maintenance. No determination of its effect on aircraft airworthiness was made before the occurrence flight. There was also no entry or report made for a stiff landing gear handle, or for difficulty engaging the landing gear handle.

There were no other known defects outstanding at the time of the occurrence.

1.7 Meteorological information

CBBC is the nearest source of meteorological observation reportsCBBC is equipped with an automated weather observation system that collects and disseminates meteorological data. and is located 0.5 nautical miles northwest of the occurrence location. The occurrence took place at approximately 1430, and the most recent automatic aerodrome routine meteorological report (METAR AUTO) was issued approximately 30 minutes before the occurrence.

The reported weather at 1400 was as follows:

- Winds from 130° true at 6 knots

- Visibility of 9 statute miles

- Light rain

- Overcast ceiling at 2800 feet AGL

- Temperature 6 °C and dew point 6 °C

- Altimeter setting 29.52 inches of mercury (inHg)

Before the occurrence flight, en route weather conditions led the pilot to divert to CBBC. However, weather conditions were not considered to be a factor during the occurrence flight.

1.8 Aids to navigation

Not applicable.

1.9 Communications

Not applicable.

1.10 Airport information

CBBC is located approximately 1.25 nautical miles north-northwest of Bella Bella and is operated by the Heiltsuk Economic Development Corp. The airport is uncontrolled, with a single, paved runway running from northwest to southeast (Runway 13/31). The runway is asphalt, 3702 feet long, and 75 feet wide, with a 1.03% negative gradient for Runway 13.NAV Canada, Canada Flight Supplement (CFS), Effective 30 November 2023 to 25 January 2024, Aerodrome/Facility Directory Canada, Bella Bella (Campbell Island) BC, section RWY DATA.

1.11 Flight recorders

The aircraft was not equipped with a flight data recorder (FDR) or a cockpit voice recorder (CVR), nor was either required by regulation.

The aircraft was equipped with a Garmin aera 760 global positioning system (GPS), a Garmin GPSMAP 276Cx GPS, and 2 Garmin GI 275 GPS units. A Spidertracks Spider X was also installed by the operator to provide real-time flight tracking of the aircraft via satellite. The Spider X collects position reports at regular intervals and then transmits them to Iridium satellites every 1 to 2 minutes. The information is then relayed to the operator.

While some of these devices are capable of recording flight data, they are not FDRs purposefully built to aid aircraft accident investigations. A partial record of the occurrence flight, 3 minutes and 10 seconds in duration, was compiled using data recovered from the Spider X, and 1 Garmin GI 275 GPS unit. This provided the investigation with details of the taxi and part of the take-off run for the occurrence flight. No information beyond the beginning of the take-off run was available, and the other GPS devices did not contain any recoverable data related to the occurrence flight.

1.11.1 TSB Recommendation A18-01

Following an accident with no survivors and no witnesses, an investigation may never be able to determine the exact causes and contributing factors unless the aircraft is equipped with an on-board recording device. The benefits of recorded flight data in aircraft accident investigations are well known and documented.

FDRs and CVRs can provide large amounts of flight data that assist investigators to determine the causes of an accident.

On 26 April 2018, the TSB issued Recommendation A18-01 calling on TC to require the mandatory installation of lightweight flight data recording systems, commonly known as lightweight data recorders (LDR) by commercial operators and private operators not currently required to carry these systems. This recommendation superseded Recommendation A13-01. The TSB urged TC to build upon the work done on Recommendation A13-01 to expedite the implementation of safety actions in response to Recommendation A18-01 which reads as follows:

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada recommends that the Department of Transport require the mandatory installation of lightweight flight recording systems by commercial operators and private operators not currently required to carry these systems.

TSB Recommendation A18-01TSB Recommendation A18-01: Mandatory installation of lightweight flight recording systems (issued 26 April 2018), at https://www.tsb.gc.ca/eng/recommandations-recommendations/aviation/2018/rec-a1801.html (last accessed on 06 November 2025).

In its December 2024 response to Recommendation A18-01, TC indicated that it is reassessing the approach and scope of LDR requirements as a result of industry consultations and feedback.

TC stated that since its previous response in December 2023, it continued working to complete additional analytical steps necessary to “determine the most appropriate course of action concerning a mandate to install LDRs and, if so, which aircraft types should be included.”Ibid.

In the TSB assessment of TC’s response, the Board expressed concern that TC may no longer be committed to LDR-mandating regulations as stated in its September 2021 update.

Further concern was expressed that TC had decided to remove the LDR regulatory file from its April 2024 – April 2026 Forward Regulatory Plan, suggesting that no regulatory action is planned before April 2026. There is no indication if or when the LDR regulatory file may be included in a future Forward Regulatory Plan.

Therefore, in March 2025, the Board indicated that it considered TC’s response to Recommendation A18-01 to be Unsatisfactory.Ibid.

1.12 Wreckage and impact information

The aircraft wreckage was located in a heavily forested area, approximately 600 m from the departure end of the runway used for takeoff. The aircraft came to rest on uneven terrain, in a nose-down attitude, rolled to the left (Figure 3).

The leading edge of each wing showed signs of impacting trees, and the outer portion of each wing was separated from the aircraft. The right engine nacelle and nose of the aircraft exhibited significant deformation. The right horizontal stabilizer was broken downward at a 90° angle. Both propellers appeared undamaged, indicating no propeller rotation at the time of the collision. The propellers were found unfeathered with the cockpit controls in the full fine position.

The occupiable space within the cockpit was partially compromised, with terrain intruding into the footwell area of the cockpit. The occupiable space within the passenger cabin was uncompromised.

The aircraft landing gear was found partially extended post-impact.

1.13 Medical and pathological information

There was no indication that the pilot’s performance was negatively affected by medical or physiological factors, including fatigue.

1.14 Fire

There was no indication of fire either before or after the occurrence.

1.15 Survival aspects

The occupiable space within the aircraft consisted of a cockpit and cabin area, separated by a bulkhead. The aircraft cockpit contained a single row of 2 seats, and the aircraft cabin was configured with 4 rows of 2 seats.

The pilot and passengers were able to egress the aircraft unassisted via the left rear cabin door. After egress, aircraft occupants followed a game trail that led to a road. Once on the road, they were found and taken to the nearest hospital by motorists.

1.15.1 Safety belts

The 2 cockpit seats were equipped with safety belts consisting of a lap strap and shoulder harness; the passenger seats in the aircraft cabin were equipped with lap straps only. All passengers were wearing their lap straps; the pilot was wearing his lap strap and shoulder harness.

The use of a safety belt that includes a shoulder harness can prevent fatal and serious injuriesNational Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), Safety Report, NTSB/SR-85/01, General Aviation Crashworthiness Project: Phase Two – Impact Severity and Potential Injury Prevention in General Aviation Accidents (15 March 1985), p. 1. as well as markedly reduce head injuries.Ibid., p. 11.

1.15.1.1 TSB Recommendation A13-03

The TSB has previously recommended (TSB recommendations A94-08 and A92-01) that small commercial aircraft be fitted with seatbelts and shoulder harnesses in all seating positions. Following these recommendations, changes to the regulations were made to require shoulder harnesses in all commercial cockpits and on all seats in aircraft manufactured after 1986 with 9 or fewer passengers.Transport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs), section 605.24: Shoulder Harness Requirements. This regulatory change did not address the vast majority of the commercial seaplane fleet, which was manufactured before 1986.

In 2013, the TSB published a reportTSB Aviation Investigation Report A12O0071. that examined an accident involving a De Havilland DHC-2 Mk. 1 Beaver that struck water in a partially inverted attitude following a go-around from an aborted water landing. In that occurrence, 1 aircraft occupant was able to exit the aircraft and was subsequently rescued. The pilot, and 1 passenger were not able to exit and drowned.

The TSB considered that, given the additional hazards associated with accidents on water, such as not being able to exit the aircraft due to incapacitation, shoulder harnesses for all seaplane passengers would reduce the risk of incapacitating injury, thereby improving the likelihood of exiting the aircraft.

As a result of this occurrence, the Board recommended that

the Department of Transport require that all seaplanes in commercial service certificated for 9 or fewer passengers be fitted with seatbelts that include shoulder harnesses on all passenger seats.

TSB Recommendation A13-03TSB Recommendation A13-03: Passenger shoulder harnesses (issued 23 October 2013), at https://www.tsb.gc.ca/eng/recommandations-recommendations/aviation/2013/rec-a1303.html (last accessed on 07 November 2025).

TC indicated in its September 2020 response to the recommendation that it did not agree with the recommendation, stating that better occupant restraint “would not produce a significant reduction in fatalities and would not offset the cost of modifying multiple models of seaplanes to install shoulder harnesses. TC does not plan to take further action in response to this recommendation.”Ibid.

The TSB’s reassessment of TC's response in March 2021 stated that the risk presented by inadequate occupant restraint is well known, is reflected in current airworthiness standards, was found to have caused or contributed to fatal injuries in previous TSB investigations, and was detailed in safety studies completed by both the TSB and the FAA. Since the TSB’s Recommendation A13-03 was issued, there have been multiple occurrences in Canada where injuries or fatalities were attributed to shoulder harnesses being unavailable to passengers in commercially operated seaplanes certificated for 9 or fewer passengers.TSB air transportation safety investigation reports A24C0057, A22P0057, and A13P0116. Therefore, it was not clear why TC indicated that, because the relative influence of this hazard cannot be quantified precisely, action will not be taken to address the safety deficiency. Therefore, the Board considered the response to Recommendation A13-03 to be Unsatisfactory.TSB Recommendation A13-03: Passenger shoulder harnesses (issued 23 October 2013), Latest response and assessment accessible, at https://www.tsb.gc.ca/eng/recommandations-recommendations/aviation/2013/rec-a1303.html (last accessed on 07 November 2025).

This TSB recommendation is currently Dormant.Ibid.

1.15.2 Emergency locator transmitter

The aircraft’s ELT did not activate. The ELT was removed from the aircraft and sent to the TSB Engineering Laboratory in Ottawa, Ontario, for analysis, where it was found to be functional and within the regulation specifications. Data on the acceleration forces experienced during the collision with terrain, which may have been insufficient to activate the ELT, were unavailable. It is unknown why the ELT did not activate.

1.16 Tests and research

1.16.1 Fuel sample analysis

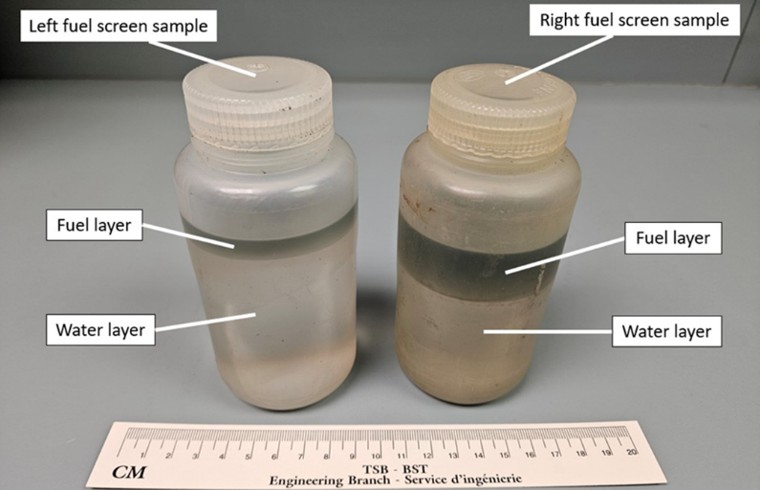

The investigation examined fuel samples from the occurrence aircraft. Two samples were taken from each of the 2 aircraft wing fuel sumps (one upon arrival at the occurrence site and the other, subsequently), and 2 were taken from the engine fuel screens (Figure 4). An additional 2 samples were extracted directly from the engine carburetors after they were received at the TSB facility in Richmond, British Columbia. In some of the samples, the fuel had separated from the water. In those cases, both layers of the fuel samples were analyzed. All of the samples were sent to a third-party laboratory for analysis.

Each fuel sample exhibited the presence of water and failed all 3 parametersThe ASTM D4176 visual test includes a clear and bright, free water, and particulate examination. of the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM) D4176 visual test. Aircraft engines may continue to run with up to a maximum of 30 parts per million (ppm) of non-dissolved water, provided it is uniformly dispersed within the fuel.Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Advisory Circular (AC) 20-125: Water in Aviation Fuels (10 December 1985), section 4.b.(4), p. 2. at https://www.faa.gov/documentLibrary/media/Advisory_Circular/AC20-125.pdf (last accessed on 07 November 2025). With the exception of the fuel layer collected from the left wing fuel sump during the 2nd sample collection, all samples had more than 30 ppm of water content, with the majority of samples in excess of 25 000 ppm25 000 ppm is the maximum value the test method employed is capable of measuring. (Table 4). The highest concentrations of water were measured in wing fuel sump locations, or in the lower settled layer of fuel samples.

Sample location | Water content (ppm) | Water content (mass %*) |

|---|---|---|

Left wing fuel sump (1st sample) | >25 000 | 93.78 |

Left wing fuel sump (2nd sample) fuel layer | 26 | <0.01 |

Left wing fuel sump (2nd sample) water layer | >25 000 | 86.11 |

Right wing fuel sump (1st sample) | >25 000 | 99.99 |

Right wing fuel sump (2nd sample) | 1393 | 0.14 |

Left carburetor fuel layer | 15 584 | 1.56 |

Left carburetor water layer | >25 000 | 97.63 |

Right carburetor | >25 000 | 83.80 |

Left engine screen fuel layer | 557 | 0.06 |

Left engine screen water layer | >25 000 | 99.80 |

Right engine screen fuel layer | 92 | <0.01 |

Right engine screen water layer | >25 000 | 84.44 |

* Mass % is an expression of the percentage of the sample that was determined to be water. A sample with a water content (mass %) of 60.0 would be 60% water and 40% fuel. The mass % value reported is the result of a measurement but is considered an estimate because it can be beyond the maximum value dictated by the scope of the test method (25 000 ppm).

1.16.2 TSB laboratory reports

The TSB completed the following laboratory reports in support of this investigation:

- LP008/2024 – NVM [non-volatile memory] Data Recovery – GPS, Flight Tracker, and EFIS [electronic flight instrument system]

- LP064/2024 - Fuel Analysis

- LP078/2024 - ELT Analysis

1.17 Organizational and management information

Wilderness Seaplanes, operating as a separate entity from Pacific Coastal Airlines Limited since May 2016,Before May 2016, the air-taxi operation that would become Wilderness Seaplanes Ltd. was a division of Pacific Coastal Airlines Limited. The 2 affiliate companies maintain common ownership. is based at CYZT and holds an air operator certificate under CARs Subpart 703 (Air Taxi Operations). At the time of the occurrence, it operated both amphibious and float-equipped aircraft in its fleet (3 Grumman G-21A Goose, 2 De Havilland DHC-2 Mk. 1 [Beaver], and 1 Cessna A185 F).

Waglisla Fuel Services Inc., which supplied the occurrence aircraft with fuel before the occurrence flight, is owned by Pacific Coastal Airlines Limited. However, Wilderness Seaplanes managed and staffed the fuel supplier at the time of the occurrence and provided the procedures and training by which aircraft fuelling was to be performed.

1.17.1 Fuelling equipment

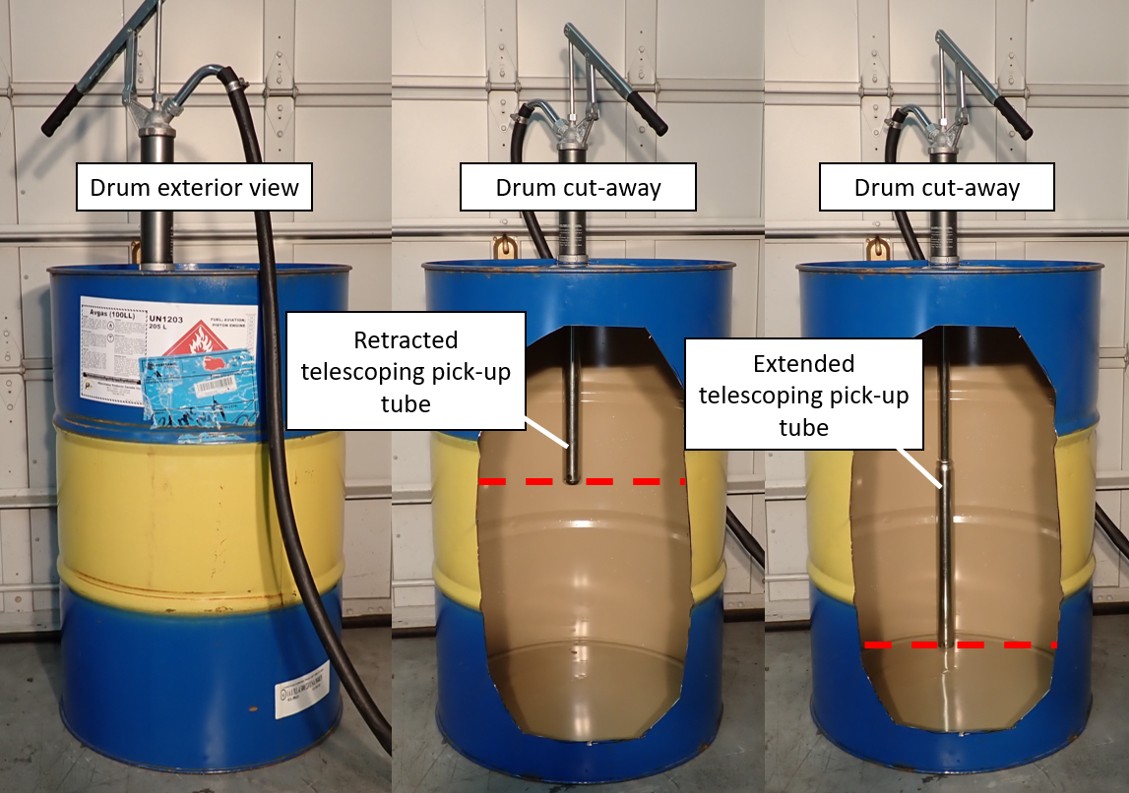

The investigation examined the equipment used to fuel the occurrence aircraft. The need for this equipment was identified by the operator approximately 3 months before the occurrence, when fuel drums were initially ordered. It included a single-stage hand pump with a telescoping pick-up tube, a ¾ inch diameter rubber hose, and a fuel nozzle. The rubber hose was attached to the hand pump and fuel nozzle with hose clamps. A wire was supplied to bond the aircraft to the fuel drum, but no means was provided to ground the fuel drum.

With respect to drum fuelling, the Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM) states that fuel should be filtered “using a proper filter and [emphasis added] water separator.”Transport Canada, TP 14371E, Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM), AIR — Airmanship, (05 October 2023), section 1.3.2: Aviation Fuel Handling, p. 385, at https://tc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/aim-2023-2_access_e.pdf (last accessed on 07 November 2025). The equipment provided by the operator did not include a particle filter or a water separator.

The hand pump provided for drum fuelling leaked fuel from its top while in use, and the pump was not a model that was suitable for use with fuel, including 100LL Avgas with which the occurrence aircraft was fuelled. After the hand pump was used for the 1st time,The hand pump was first used approximately 7 weeks before the occurrence. When the hand pump was used to fuel another aircraft and the occurrence aircraft on the day of the occurrence flight, it was the 2nd and last time the pump was used. the operator decided to replace it with an electric pump because the hand pump leaked and transferred fuel at a slow rate. It was planned to introduce the electric pump to service by the end of December 2023. On the day of the occurrence, the replacement pump was not yet available, and the hand pump was still in service.

The threaded outlet on the hand pump, to which the hose was attached with a hose clamp, used ¾-inch NHR thread, commonly used for garden hose applications.The American Society of Mechanical Engineers, ASME B1.20.7-1991: Hose Coupling Screw Threads (Inch) (16 April 1992), p. 1. Fuel particle filters, water separators, and the rotary hand pumps commonly used for drum fuelling are equipped with 1-inch National Pipe Taper (NPT) thread.Ibid., p. 4 NHR thread and NPT thread are not compatible connectionsNorth Shore Crafts, What Type Of Thread is Used In Garden Hoses: A Comprehensive Guide (09 October 2024), at https://northshorecrafts.com/what-type-of-thread-is-garden-hose/?srsltid=AfmBOoq5Wq2Ma2LUHpbRIk_0RvyLtuHfjwxfAxVmpbpfobsPkM8OKzgR (last accessed on 07 November 2025). and the hand pump would have required an adapter to incorporate the filters recommended in the TC AIM.Transport Canada, TP 14371E, Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM), AIR — Airmanship, (05 October 2023), section 1.3.2: Aviation Fuel Handling, p. 385, at https://tc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/aim-2023-2_access_e.pdf (last accessed on 07 November 2025).

Wilderness Seaplanes did not supply water detection pasteWater detection paste is a substance that changes colour upon contact with water. It is commonly used to aid in the detection of water within fuel supplies. for drum fuelling operations because the operator understood the purpose of water detection paste to be to determine the level of water in the bottom of a large, permanent tank installation rather than to determine the presence of water within a sample taken from a fuel drum.

1.17.2 Fuel source

The fuel type used by the occurrence aircraft, 100LL Avgas, is normally available at CBBC from a fuel truck. Approximately 2 months before the occurrence, this fuel truck was removed from service and sent for repair due to mechanical issues. Fuel drums were brought to the airport as an interim means of providing 100LL Avgas.

On the subject of storing fuel drums, TC states that “All fuel drums should be stored on their side, with vents and bungs at the 3 o’clock and 9 o’clock positions”Transport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 5, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 07 November 2025). (Figure 5). The fuel drum used to fuel the occurrence aircraft was stored by the operator in an upright orientation.

It was reported that Wilderness Seaplanes’ intention was to discard any fuel that remained in a drum after it had been unsealed and used for aircraft fuelling. This policy was not found documented in company procedures or written communications to pilots.

Approximately 7 weeks before the occurrence, the drum from which the occurrence aircraft was fuelled had been unsealed and opened in anticipation of being used to fuel another Wilderness Seaplanes aircraft. No fuel was taken from the drum on that occasion, and once it was determined the drum was not required, the bung of the drum was reinserted. The plastic seal that covers the bung, once removed, cannot be reinstalled. The drum was not marked or labelled as having been opened and was returned to storage rather than isolated or quarantined as an unsealed drum. When the drum was opened by the occurrence pilot on the day of the occurrence, the threaded bung was found to be only finger tight.

1.17.3 Aircraft fuelling

The investigation examined the drum fuelling procedures used on the day of the occurrence. Two aircraft were fuelled from the occurrence fuel drum, the 1st being a Beaver, also owned by Wilderness Seaplanes.

A pallet with 4 fuel drums, including the occurrence drum, was brought from the drum storage area to the aircraft using a forklift operated by a Wilderness Seaplanes fuel agent. Before fuelling, communication occurred between this fuel agent and the pilot of the Beaver. Following this communication, the fuel agent did not take part in fuelling the 2 aircraft from the occurrence drum. It is unknown exactly what was communicated; however, the fuel agent had previous experience using the hand pump and may have attempted to explain how to extend its pick-up tube.

Wilderness Seaplanes’ standard operating procedures (SOPs) state that:

[f]or safety reasons, fuelling the Goose is a 2 person job. Pilots are expected to fuel their aircraft. Fuel agent will stand by to pass the fuel hose up and to receive it when fuelling is completed.Wilderness Seaplanes Ltd., Standard Operating Procedures: Grumman G21A Goose – Land and Water Operations, Amendment #3 (December 2023), section 2.7: Fueling, p. 2-11.

On the day of the occurrence, fuelling was completed by the pilot of the occurrence aircraft, assisted by the pilot of the Beaver.

Before the hand pump was installed into the fuel drum, its telescoping pick-up tube was not extended to its full length (Figure 6). As a result, when a sample of fuel was pumped from the drum into a glass jar, the fuel that was examined was drawn from the mid-height of the drum, rather than the lowest point. The fuel sample that was examined passed the visual clear and bright test but was not representative of the fuel in the lower portion of the drum. After sampling, the Beaver was fuelled.

After fuelling of the Beaver was completed, the occurrence pilot fuelled the occurrence aircraft while the Beaver pilot operated the hand pump. Because the telescoping pick-up tube of the hand pump had not been fully extended, the flow of fuel stopped once it was drawn down to the approximate halfway point of the drum. The Beaver pilot then uninstalled the hand pump and extended the telescoping pick-up tube before reinstalling the pump and resuming fuelling. The remaining contents of the drum accessible by the fully extended telescoping pick-up tube was pumped into the occurrence aircraft. A fuel sample from the lower portion of the drum was not taken or examined.

With respect to examining the fuel in an aircraft during a pre-flight check, the TC AIM states the following:

[d]uring the pre-flight check, a reasonable quantity of fuel should be drawn from the lowest point in the fuel system into a clear glass jar. A “clear and bright” visual test should be made to establish that the fuel is completely free of visible solid contamination and water[...]Transport Canada, TP 14371E, Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM), AIR — Airmanship, (05 October 2023), section 1.3.2: Aviation Fuel Handling, p. 385, at https://tc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/aim-2023-2_access_e.pdf (last accessed on 07 November 2025).

After the occurrence aircraft was fuelled, a sample was not taken from the aircraft wing fuel sumps, or any other part of the aircraft, during the aircraft’s pre-flight inspection.

1.17.4 Company procedures

The Wilderness Seaplanes Company Operations Manual contains guidance on when aircraft pre-flight inspections must occur, but it does not detail these inspections or discuss draining or sampling of aircraft fuel systems. Wilderness Seaplanes had 2 company documents that contained guidance on fuel sampling for the occurrence aircraft type: the Grumman G-21A “Goose” Flight ManualPacific Coastal Airlines, Grumman G-21A “Goose” Flight Manual, Revision #2 (05 November 2008), Appendix II: Daily Inspection Checklist. and the Goose SOPs.Wilderness Seaplanes Ltd., Standard Operating Procedures: Grumman G21A Goose – Land and Water Operations, Amendment #3 (December 2023), section 2.1: Daily Inspection Checklist, Cockpit, p. 2-4.

The flight manual contains a daily inspection checklist. This checklist itemizes draining the wing fuel sumps using a fuel strainer cup as part of the daily inspection.Pacific Coastal Airlines, Grumman G-21A “Goose” Flight Manual, Revision #2 (05 November 2008), Appendix II: Daily Inspection Checklist. The flight manual does not indicate if the daily inspection is to be performed before each flight, or at the beginning of the aircraft’s operational day; however, the investigation determined that Wilderness Seaplanes’ expectation was that pilots would drain aircraft wing fuel sumps only before an aircraft’s 1st flight of the day and, although required by the flight manual, there was no expectation that fuel samples be collected or examined during this procedure.

The operator’s SOPs for the Goose contain a different daily inspection checklist that is more detailed than the one found in the flight manual. With respect to sampling fuel from the aircraft as part of a daily inspection, this checklist requires that each of the aircraft’s 2 wing fuel sumps be drained for 5 seconds. This checklist further states that the fuel sample can be captured for inspection, but it does not mandate this collection or describe how it should be done,Wilderness Seaplanes Ltd., Standard Operating Procedures: Grumman G21A Goose – Land and Water Operations, Amendment #3 (December 2023), section 2.1 Daily Inspection Checklist, Cockpit, p. 2-4. unlike the checklist in the flight manual, which specifies that a fuel strainer cup must be used.Pacific Coastal Airlines, Grumman G-21A “Goose” Flight Manual, Revision #2 (05 November 2008), Appendix II: Daily Inspection Checklist. The company pilots regularly drained wing fuel sumps onto the ground before the 1st flight of the day, with no fuel sample collected.

Collecting a fuel sample from the wing fuel sumps of the Goose requires that a valve be operated in the cockpit while the sample is collected from outside the aircraft, ahead of where the main landing gear retracts. One sample is to be collected from each side of the aircraft exterior. It is reportedly possible for 1 person to perform the sampling without assistance by manipulating the valve in the cockpit with 1 hand, and reaching to each wing fuel sump outlet through the cockpit side windows with the other hand. This method of collecting samples, without the assistance of a 2nd person, is difficult and presents ergonomic challenges.

The investigation examined 1 instance of the wing fuel sumps of the occurrence aircraft being drained before a flight in a video recorded in 2021. In that instance, it was observed that the left wing fuel sump was drained for approximately 2 seconds, and the right wing fuel sump was drained for approximately 3 seconds. The samples were not collected or examined by the pilot operating the aircraft.S. Doucette, Grumman G-21 Goose at Sechelt airport [video] (08 May 2021), 3:38 to 4:14, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b72qNDtFbbA&t=210s (last accessed on 12 November 2025).

Foregoing the collection and examination of fuel samples as part of pre-flight inspections, after fuelling, and as part of the aircraft daily inspection had become normalized at Wilderness Seaplanes. A container that could be used to collect fuel samples from the aircraft wing fuel sumps was supplied by the operator with the drum fuelling equipment, but it was not normally supplied by the operator to pilots, or carried on board the aircraft.

The operator’s Company Operations Manual, flight manual, and SOPs contained no information with respect to fuelling aircraft from fuel drums. There were also no written communications such as memos, emails, or safety bulletins regarding drum fuelling.

1.17.5 Pilot training

TC’s Study and Reference Guide for written examinations for the Commercial Pilot Licence – Aeroplane, defines the knowledge requirements to hold a Canadian commercial pilot licence. This document lists fuel handling and aircraft fuelling as required knowledge but does not list any knowledge specific to drum fuelling.Transport Canada, Study and Reference Guide for written examinations for the Commercial Pilot Licence – Aeroplane, Sixth Edition (November 2009), Pre-flight and Fuel Requirements, p. 8, at https://tc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/migrated/tp_12881e.pdf (last accessed on 12 November 2025). TC’s Flight Test Guide – Commercial Pilot Licence – Aeroplane does not list aircraft fuelling, or drum fuelling, as a flight test item.Transport Canada, TP 13462E, Flight Test Guide – Commercial Pilot Licence – Aeroplane, Sixth Edition (January 2021), at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/flight-test-guide-commercial-pilot-licence-aeroplane-tp-13462e#ex2d (last accessed on 12 November 2025). TC’s Instructor Guide – Seaplane Rating does include information on fuelling from barrels, but it notes the exercise is not required.Transport Canada, TP 12668E, Instructor Guide – Seaplane Rating (May 1996), Part 6: Advanced Exercises, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/instructor-guide-seaplane-rating-tp-12668/part-6-advanced-exercises#fuelling (last accessed on 12 November 2025).

Wilderness Seaplanes requires a commercial pilot licence with a multi-engine and seaplane rating to operate the occurrence aircraft type. TC’s requirements to obtain these qualifications do not include mandatory training on fuelling aircraft from drums.

The investigation determined that no training was provided by Wilderness Seaplanes to company pilots about fuelling aircraft from fuel drums.

1.18 Additional information

1.18.1 Practices recommended by regulators when fuelling aircraft from drums

The investigation examined the recommended best practices for drum fuelling of aircraft published by TC, the FAA, the U.S. Department of the Interior Office of Aviation Services, and the Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority. The following sections present a composite of the practices recommended by these 4 agencies.

1.18.1.1 Drum storage

Fuel drums should be stored on their sides;Transport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 5, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 14 November 2025).,Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority, “Drum refuelling” [video] (09 December 2012), 0:54 to 0:57, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4dujKldZX8 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). off the ground on wooden rails,Ibid., 1:00 to 1:02. pallets, or dunnage;U.S. Department of the Interior, “DOI Operational Procedures Memorandum (OPM) – 20: Drum Fuel Management” (effective 01 January 2023), section 4B.3), p. 1. and with vents and bungs at the 3 and 9 o'clock positions.Transport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 5, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 14 November 2025).,Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority, “Drum refuelling” [video] (09 December 2012), 1:05 to 1:08, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4dujKldZX8 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). Vents, bungs, or openings should be below the fluid level within the drum.Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Advisory Circular (AC) 20-125: Water in Aviation Fuels (10 December 1985), section 7.a.(5)(i), pp. 5 and 6. Drums should be chocked, blocked, or braced to prevent rolling.Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority, “Drum refuelling” [video] (09 December 2012), 1:03 to 1:04, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4dujKldZX8 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). Whenever possible, drums should be stored in sheltered, secondary containmentU.S. Department of the Interior, “DOI Operational Procedures Memorandum (OPM) – 20: Drum Fuel Management” (effective 01 January 2023), section 4B.1), p. 1. and protected from the sun and weather.Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Advisory Circular (AC) 20-125: Water in Aviation Fuels (10 December 1985), section 7.a.(5)(i), p. 5. Drums containing different fuel types should be stored in separate areas, at least 50 feet apart.U.S. Department of the Interior: Office of Aviation Services, Aviation Fuel Management Handbook (September 2024), chapter 6: Drum/Barrel Fuel, section 6.2: Storage, 4th bullet point, p. 36, at https://www.doi.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2024-09/doi-aviation-fuel-management-handbook-sept-2024.pdf (last accessed on 14 November 2025).,U.S. Department of the Interior, “DOI Operational Procedures Memorandum (OPM) – 20: Drum Fuel Management” (effective 01 January 2023), section 4B.4), p. 1.

1.18.1.2 Drum inspection

Before fuelling, the fuel drum should be examined. The drum label should be checked to ensure the drum contains the correct type and grade of fuel.Transport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 1, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 14 November 2025).,Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority, “Drum refuelling” [video] (09 December 2012), 0:22 to 0:25, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4dujKldZX8 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). The drum fill date should be verified to ensure the fuel is not too old to be safely used.Transport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 2, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 14 November 2025).,Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority, “Drum refuelling” [video] (09 December 2012), 3:00 to 3:04, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4dujKldZX8 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). Recommendations on maximum fuel age range from 12Ibid., 0:35 to 0:37. to 24Transport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 2, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). months and may vary with fuel type.U.S. Department of the Interior, “DOI Operational Procedures Memorandum (OPM) – 20: Drum Fuel Management” (effective 01 January 2023), section 4B.7), p. 2. It should be verified that the bung seal is intact to ensure fuel has not been tampered with.Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority, “Drum refuelling” [video] (09 December 2012), 3:04 to 3:10, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4dujKldZX8 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). The drum should be checked for writing or markings; an X is often used to indicate that a drum contains contamination.Transport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 3, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). A drum may be marked with a date, aircraft registration, and the approximate amount of fuel used, if it was partially used.Ibid. In this case, how long the drum has been in an unsealed condition should be taken into consideration. The drum should be inspected for external damage. External damage to the drum may cause the epoxy paint that lines the drum to peel away from the internal surface and contaminate the fuel.Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority, “Drum refuelling” [video] (09 December 2012), 2:43 to 3:00, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4dujKldZX8 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). The interior of the drum can be examined visually through the bung hole, ideally with an explosion-proof flashlight.U.S. Department of the Interior, Office of Aviation Services, Aviation Fuel Management Handbook (September 2024), chapter 6: Drum/Barrel Fuel, section 6.3: Dispensing, 3rd bullet point, p. 37, at https://www.doi.gov/sites/default/files/documents/2024-09/doi-aviation-fuel-management-handbook-sept-2024.pdf (last accessed on 14 November 2025).

1.18.1.3 Analysis of drum fuel sample

A sample can be collected from the lowest accessible fuel in the drum by pumping the first strokes into a container, which will ensure any contamination downstream of the pump filters will be flushed out.Transport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 13, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). A sample may also be collected with a length of tube inserted to the lowest point in the drum by plugging the top end of the tube with a thumb, then releasing the thumb seal to discharge the sample into a container.Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority, “Drum refuelling” [video] (09 December 2012), 3:13 to 3:19, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4dujKldZX8 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). Swirling the fuel sample can make any sediment contained within more visible.Ibid., 3:29 to 3:32. In addition to visually inspecting the sample, it should always be tested using water detection paste.Ibid., 3:32 to 3:37.,Transport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 11, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). The paste should be applied to a clean dry dowel or screwdriver, and swirled throughout the fuel sample.Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority, “Drum refuelling” [video] (09 December 2012), 3:37 to 3:40, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4dujKldZX8 (last accessed on 14 November 2025).

1.18.1.4 Electrical bonding and grounding

Bonding connects metal materials to create a complete electrical circuit so that none of the individual parts have electricity building up in them. The bonded circuit then needs to be connected to the ground to safely allow the electricity to drain to the earth.Ibid., 4:05 to 4:08. Bonding and grounding the aircraft and fuelling equipment is required to prevent a spark from igniting fuel vapour while drum fuelling.Transport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 9, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 14 November 2025).,Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority, “Drum refuelling” [video] (09 December 2012), 3:55 to 4:03, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4dujKldZX8 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). Grounding requires that the fuel drum be bonded to a ground post.Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (10 July 2023), Chapter 7: Refueling Procedures, p. 7-29, at https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/aviation/phak (last accessed on 14 November 2025). The condition of bonding and grounding cables should be checked before use.Transport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 9, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). When grounding and bonding, the following order should be observed: drum to ground (ground post), drum to pump, pump to aircraft, and nozzle to aircraft, all before the aircraft fuel cap is opened. When finished fuelling, reverse the order.Ibid.,Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority, “Drum refuelling” [video] (09 December 2012), 4:05 to 4:08, 4:25 to 4:32, and 4:50 to 5:00, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4dujKldZX8 (last accessed on 14 November 2025).,Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (10 July 2023), Chapter 7: Refueling Procedures, p. 7-29, at https://www.faa.gov/regulations_policies/handbooks_manuals/aviation/phak (last accessed on 14 November 2025).

1.18.1.5 Dispensing

The pick-up tube must not reach the lowest point in the drum so that the lowest portion of fuel, likeliest to be contaminated, is not pumped into the aircraft.Transport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 6b, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). The fuel filters used for drum fuelling should be replaced, at a minimum, annually.U.S. Department of the Interior, “DOI Operational Procedures Memorandum (OPM) – 20: Drum Fuel Management” (effective 01 January 2023), section 4C.7), p. 2. Filters should also be changed if a reduction in flow rate is observed.Ibid., section 4C.8). Fuel should pass through both a fuel particle filter and a water separator,Transport Canada, TP 14371E, Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM), AIR – Airmanship (05 October 2023), section 1.3.2: Aviation Fuel Handling, p. 385 at https://tc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/aim-2023-2_access_e.pdf (last accessed on 14 November 2025). or a particle filter and an expanding go-no-go filterTransport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 12, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). before being dispensed into the aircraft. The particle filter used should be a 5-micron filter, suitable for use with fuel.Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Advisory Circular (AC) 20-125: Water in Aviation Fuels (10 December 1985), section 7.a.(5)(iii), p. 6. Drum fuelling must take place a safe distance from buildings, other aircraft, and people not involved in fuelling operations.Australian Government Civil Aviation Safety Authority, “Drum refuelling” [video] (09 December 2012), 1:14 to 1:43, at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q4dujKldZX8 (last accessed on 14 November 2025).

1.18.1.6 Analysis of aircraft fuel sample

After fuelling, the aircraft pre-flight inspection must include draining, collecting, and examining fuel samples from the low points of the aircraft fuel system.Transport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 15, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 14 November 2025).,Transport Canada, TP 14371E, Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM), AIR – Airmanship (05 October 2023), section 1.3.2: Aviation Fuel Handling, p. 385, at https://tc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/aim-2023-2_access_e.pdf (last accessed on 14 November 2025). Each sample should be 10 ounces (approximately 300 ml) or more, and should be examined using a transparent container.Ibid.,Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Advisory Circular (AC) 20-125: Water in Aviation Fuels (10 December 1985), section 5.b., p. 2. Samples should be collected before moving or disturbing the aircraft.Transport Canada, TP 2228E-13, Take Five…for safety: Fuel Drum Etiquette, (April 2003), item 15, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/aviation/publications/take-fivefor-safety-tp-2228/fuel-drum-etiquette-tp-2228e-13 (last accessed on 14 November 2025). Pilots must be familiar with the specific requirements of sampling fuel from their aircraft. To obtain a representative fuel sample, it may be necessary to drain reservoirs, gascolators, or filters in addition to fuel sumps.Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Advisory Circular (AC) 20-125: Water in Aviation Fuels (10 December 1985), paragraph 6.d.(1), p. 4. Effective sampling may require the operation of fuel pumps or cross-feed valves, and tail-wheel aircraft may require raising the tail to a level flight attitude to ensure water flows to a gascolator or fuel strainer.Ibid., paragraph 7.c.: Aircraft Fuel Tanks. pp. 6 and 7.

1.18.1.7 Drum fuelling

Even when every precaution is followed, the regulators make it clear that, due to the associated risks, drum fuelling should not occur if other options are available. TC states: “[t]he use of temporary fuelling facilities such as drums or cans is discouraged.”Transport Canada, TP 14371E, Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM), AIR – Airmanship (05 October 2023), section 1.3.2: Aviation Fuel Handling, p. 385, at https://tc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/2023-10/aim-2023-2_access_e.pdf (last accessed on 17 November 2025). Also, the FAA states: “[r]efueling from drum storage [emphasis in original] or cans should be considered as an unsatisfactory operation and one to be avoided whenever possible.”Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), Advisory Circular (AC) 20-125: Water in Aviation Fuels (10 December 1985), section 7.a.(5), p. 5.

1.18.2 TSB air transportation safety issue investigation report on air-taxi operations in Canada

In 2019, the TSB published Air Transportation Safety Issue Investigation (SII) Report A15H0001.TSB Air Transportation Safety Issue Investigation Report A15H0001: Raising the bar on safety: Reducing the risks associated with air-taxi operations in Canada. The objective of this SII was to improve safety by reducing the risks in air-taxi operations across Canada. The air-taxi sector continues to experience more accidents and more fatalities than any other in the commercial aviation industry.

Phase 1 of the SII included an examination of 167 TSB investigation reports involving both fixed-wing and rotary-wing aircraft. This examination found that most fatalities involved flights that ended in either controlled flight into terrain or a loss of control. An analysis of accident data found that contributing factors fell into 2 broad areas:

- acceptance of unsafe practices; and

- inadequate management of operational hazards.

In Phase 2 of the SII, investigators conducted interviews with industry stakeholders to better understand the pressures faced by the industry, as well as the issues encountered in daily activities. The information gathered was organized into 19 safety themes that, after further analysis using additional data, yielded various conclusions. Of the 19 themes, the following 3 and their respective conclusions are relevant to this investigation:

- Acceptance of unsafe practices, which can lead to an increased risk of an accident if they are not recognized and mitigated or if they are accepted over time as the “normal” way to conduct business.

- Training of pilots and other flight operations personnel, which is essential for them to develop the skills and knowledge they need to effectively manage the diverse risks associated with air-taxi operations.

- Pilot decision making/crew resource management, which are critical competencies that help flight crews manage the risks associated with aircraft operations.

2.0 Analysis

The analysis of this occurrence will focus on the circumstances and conditions that contributed to the dual engine failure and the resulting accident. These circumstances and conditions include fuel drum storage, the equipment provided for fuelling, the pilot training provided by Wilderness Seaplanes Ltd. (Wilderness Seaplanes), company procedures, and aircraft pre-flight inspections. The risks associated with the latent aircraft mechanical defect, safety belts installed in the aircraft, and not carrying data recorders will also be discussed.

2.1 Fuel drum storage

The fuel drum used to fuel the occurrence aircraft was stored outdoors in an upright orientation. Guidance from Transport Canada (TC) states that fuel drums should be stored on their sides, with vents and bungs oriented to minimize the ingress of water. This defence against water ingress was not implemented because the operator was unaware of TC’s guidance with respect to fuel drum storage. As a result, water entered the drum by the openings on its top, contaminating the fuel inside.

The drum was also stored unmarked after having been unsealed and was reintroduced to the supply of unopened fuel drums rather than being isolated or quarantined as an unsealed drum. TC guidance states that unsealed drums should be marked with an X. Because the pilot and fuel agent who originally handled the opened drum had not been trained to mark or isolate an unsealed drum, and because the operator had no written procedures to describe these practices, these defences were not used.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

The operator did not store fuel drums in a way that minimized the possibility of fuel contamination because the operator was not aware of TC’s fuel drum storage guidelines. As a result, the occurrence fuel drum was stored upright, and water likely entered via the vent or bung and contaminated the fuel.

2.2 Fuelling equipment

The drum fuelling equipment provided by Wilderness Seaplanes did not include several commonly used defences intended to prevent the introduction of contamination to an aircraft fuel system.

Although guidance in the Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM) recommends using a water separator and a particle filter when drum fuelling, these were not available when the occurrence aircraft was fuelled. The operator did not believe this equipment was a necessary precaution as it was anticipated that fuelling would only be carried out from new and unopened factory-sealed fuel drums. In the event an opened drum was not completely consumed during fuelling, the operator planned that any remaining fuel in the drum would not be used. This was believed to be a sufficient defence against introducing contaminated fuel from a drum into an aircraft.

A go-no-go filter, which expands upon contact with water and thereby prevents the flow of fuel within the delivery system, was believed to present a risk of getting an aircraft stuck at the airport if the activated water filter rendered the hand pump unusable. This concern contributed to the decision to exclude water filtration from the drum fuelling system.

The fuel pump provided for drum fuelling was not suitable for use with gasoline or 100LL Avgas. The pump was originally purchased by the operator to transfer waste fuel between drums, rather than to fuel aircraft. The fact that the pump was not suitable for gasoline or 100LL Avgas was not identified by the operator.

Because the threading on the fuel pump outlet was NHR thread, rather than the National Pipe Taper (NPT) thread standard used by drum fuelling equipment, filters could not be added to the pump without the use of an adapter. The need for an adapter presented an obstacle to the use of any filters the operator may have had in inventory if the appropriate adapters were not also on hand.

When the need for a pump for fuelling aircraft from drums was identified by the operator, the occurrence pump was chosen because it was already in the operator’s possession, and it was thought that it could be suitably adapted for aircraft fuelling by adding a hose and nozzle held in place by hose clamps. When the pump was first used, it was discovered that it leaked fuel from its top and pumped at a slow rate. After the pump’s 1st use, a decision was made to replace it with an electric model; however, the new pump had not been introduced at the time of the occurrence, and the old pump had not been removed from service.

Water detection paste, which changes colour when exposed to water, is also recommended by TC when drum fuelling. This defence was not employed because the operator believed the risk of water contamination in the new, sealed drums that were to be used was negligible. The operator also understood the purpose of water detection paste to be to determine the level of water in the bottom of a large, permanent tank installation rather than to determine the presence of water within a sample taken from a fuel drum.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

The operator did not consider the hazards related to fuelling from previously opened or contaminated fuel drums. As a result, physical defences commonly used to detect contamination, such as filters or water detection paste, were not implemented.

2.3 Company procedures

Wilderness Seaplanes did not have written procedures, policies, or instructions for drum fuelling of aircraft. This was in part because the operator had planned to change the pump used for drum fuelling from a hand pump to an electric pump. Rather than provide a policy that would have to be amended to account for a change in equipment, the operator elected to delay the implementation of a written policy until after the electric pump had been introduced.

The operator anticipated the probability of drum fuelling an aircraft before the implementation of a written procedure to be unlikely. This was because company aircraft did not normally refuel at CBBC, and the fuel drums located there were considered an unlikely contingency. The operator anticipated the risk presented by not having written procedures to be negligible because of the perception that procedures would be in place before drum fuelling was likely to occur. However, without concomitant direction to not fuel from drums until the written procedures were in place, a risk associated with drum fuelling remained.

The operator believed that drum fuelling of aircraft, if required, was a straightforward task that would be familiar to most of its pilots. However, no steps were taken to verify pilot understanding or experience. As a result, the operator held an inaccurate assessment of pilot knowledge, skill, and risk with respect to the task. This contributed to the operator underestimating the risk of introducing drum fuelling to its operation, thereby reducing the perceived need for written procedures.

Communication about the new drum fuelling practices at CBBC was informal in nature, with no official notifications issued to the pilot group or aircraft fuel agents. Without written procedures for performing a task, company personnel may infer that they are expected to figure it out on their own. The absence of both training and written policy is likely to be interpreted as indications that a task is simple and without risk.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

Because drum fuelling operations were new and in the process of changing, the operator delayed the communication of specific procedures describing how to safely perform the task.

2.4 Pilot training

While it may seem like a relatively straightforward task, safely fuelling aircraft from drums requires the use of specialized equipment and involves precautions beyond those required for fuelling operations from permanent tank installations or from fuel trucks. Training on the use of this equipment, and the relevant procedures, is not part of the required curriculum for any pilot licence or rating in Canada. TC guidance states that drum fuelling is discouraged, and guidance from the U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) states that it should be avoided whenever possible, indicating a greater risk than for regular fuelling operations.

It is therefore important that operators who choose to include drum fuelling in their operations provide the requisite training to pilots, along with any staff member who is expected to perform the task of drum fuelling.

The pilots who fuelled the occurrence aircraft had not received training on drum fuelling from Wilderness Seaplanes because the operator believed that pilots would have prior experience with drum fuelling and that the process would be simple enough to perform without training. This belief was the result of the operator not being aware of the complexity of drum fuelling and of each pilot’s prior experience with the task. Because no training was provided, defences against introducing contamination to the aircraft fuel system were omitted or were not successfully employed by the personnel who performed the task.

Findings as to causes and contributing factors

Training was not provided on the equipment or procedures for drum fuelling by the operator because it was perceived to be a simple task, and it was believed that company pilots would have prior experience with drum fuelling.

Because there were no physical defences, no specific procedures, and no training, water contamination was introduced into the fuel system when the aircraft was fuelled.

2.5 Aircraft pre-flight inspection

After fuelling the occurrence aircraft but before the occurrence flight, the pre-flight aircraft inspection did not include collecting or inspecting fuel from the aircraft fuel system. The TC AIM states that a reasonable quantity of fuel should be drawn from the lowest point in an aircraft’s fuel system and collected in a clear container for a visual inspection as part of a pre-flight check. This practice provides a defence against fuel contamination from a variety of sources, including contamination introduced during aircraft fuelling.

Draining or sampling the aircraft fuel sumps was only required by the operator’s standard operating procedures (SOPs) before the aircraft’s 1st flight of the day. Because the occurrence flight was not the aircraft’s 1st flight of the day, the fuel sumps were not drained or sampled before the occurrence flight.

It had become normalized for Wilderness Seaplanes personnel to not collect and examine a fuel sample when the wing fuel sumps of the Grumman G-21A Goose were drained. This normalization occurred because of operator expectations, ergonomic challenges associated with collecting a fuel sample without assistance from a 2nd person, and the absence of a suitable container to collect samples available on board the aircraft.

Because collecting and examining fuel samples was typically omitted when fuel sumps were drained, sample collection and examination was not considered when the aircraft was fuelled from a drum. Furthermore, the risks inherent to drum fuelling were not fully understood by the operator. As a result, the contaminated fuel introduced into the aircraft fuel system was not detected before the occurrence flight.

Findings as to causes and contributing factors

Company guidance required fuel to be sampled only as part of the daily inspection, and the practice of omitting fuel sampling had become normalized. As a result, the contamination that was introduced into the fuel system was not detected before departure.

As a result of fuel contamination, the left and right engines lost power shortly after departure. The pilot performed a forced landing in a wooded area, which resulted in substantial damage to the aircraft and minor injuries to the 5 occupants.

2.6 Aircraft mechanical state

At the time of the occurrence, the aircraft was being operated with an inoperative electrical landing gear retraction system, and the landing gear could only be retracted using the alternate, manual system. The landing gear selector, which operated the electrical landing gear retraction system, had previously been recorded as being stiff. This may have made it difficult to differentiate if the landing gear selector was unserviceable or just stiff. As a result, this defect was not documented in the aircraft journey log or reported to company dispatch or maintenance.

When both engines failed during the occurrence, the aircraft landing gear was not fully retracted. This condition increased the total drag of the aircraft, thereby reducing glide performance. An attempt was made to retract the landing gear using the manual system, which increased the pilot’s workload during the emergency. The attempt to retract the landing gear was unsuccessful in the time available.

Finding as to risk

If pilots knowingly operate aircraft with an outstanding mechanical issue, there is a risk that it will compound the severity or increase the complexity of any subsequent abnormal or emergency situation.

2.7 Safety belts

Some injuries sustained by passengers during the occurrence may have been mitigated by the use of shoulder harnesses had they been available as part of the safety belt system for seats in the aircraft cabin. The aircraft, as manufactured, did not include shoulder harnesses as part of the safety belts for passenger seats because this was not a requirement at the time the aircraft was manufactured. TC requirements for the occurrence aircraft only mandated that the pilot seat and any seat beside the pilot seat be equipped with a shoulder harness. Because the aircraft was not designed with passenger shoulder harnesses, and TC did not require them, none were installed.

The TSB made a recommendation in 2013 calling for light seaplanes, such as the occurrence aircraft, to be fitted with safety belts that included shoulder harnesses on all passenger seats. The recommendation was specifically targeted to address the possible effect of injury-related incapacitation when an underwater egress is required; however, the risk of injury for passengers flying in light aircraft without shoulder harnesses, regardless of landing surface, remains elevated.

Finding as to risk

If light aircraft are not equipped with safety belts that include shoulder harnesses on all passenger seats, there is an increased risk of passenger injury as a result of flailing and/or contact with the aircraft structure.

2.8 Lightweight data recorders

The occurrence aircraft did not have a lightweight data recorder (LDR), nor was it required to by regulation. The TSB laboratory analyzed aircraft performance from the time that avionics were powered until the end of the available data during the aircraft’s take-off roll. Because the aircraft was not equipped with a LDR, the investigation had no data for the majority of the flight and was unable to analyze aircraft performance at the time of the occurrence.

The TSB made a recommendation in 2018 calling for the installation of LDRs by commercial operators and private operators not currently required to carry these systems. This recommendation superseded a recommendation from 2013 and was issued to address the absence of flight data that often precludes investigators from fully identifying and understanding an accident’s sequence of events, underlying causes, and contributing factors.

Finding as to risk

If commercial and private aircraft are not equipped with an LDR, crucial flight data may not be available to investigators after an accident, increasing the risk of not being able to determine the underlying causes and advance transportation safety.

3.0 Findings

3.1 Findings as to causes and contributing factors

These are the factors that were found to have caused or contributed to the occurrence.

- The operator did not store fuel drums in a way that minimized the possibility of fuel contamination because the operator was not aware of Transport Canada’s fuel drum storage guidelines. As a result, the occurrence fuel drum was stored upright, and water likely entered via the vent or bung and contaminated the fuel.

- The operator did not consider the hazards related to fuelling from previously opened or contaminated fuel drums. As a result, physical defences commonly used to detect contamination, such as filters or water detection paste, were not implemented.

- Because drum fuelling operations were new and in the process of changing, the operator delayed the communication of specific procedures describing how to safely perform the task.

- Training was not provided on the equipment or procedures for drum fuelling by the operator because it was perceived to be a simple task, and it was believed that company pilots would have prior experience with drum fuelling.

- Because there were no physical defences, no specific procedures, and no training, water contamination was introduced into the fuel system when the aircraft was fuelled.

- Company guidance required fuel to be sampled only as part of the daily inspection, and the practice of omitting fuel sampling had become normalized. As a result, the contamination that was introduced into the fuel system was not detected before departure.

- As a result of fuel contamination, the left and right engines lost power shortly after departure. The pilot performed a forced landing in a wooded area, which resulted in substantial damage to the aircraft and minor injuries to the 5 occupants.

3.2 Findings as to risk

These are the factors in the occurrence that were found to pose a risk to the transportation system. These factors may or may not have been causal or contributing to the occurrence but could pose a risk in the future.

- If pilots knowingly operate aircraft with an outstanding mechanical issue, there is a risk that it will compound the severity or increase the complexity of any subsequent abnormal or emergency situation.

- If light aircraft are not equipped with safety belts that include shoulder harnesses on all passenger seats, there is an increased risk of passenger injury as a result of flailing and/or contact with the aircraft structure.

- If commercial and private aircraft are not equipped with a lightweight data recorder, crucial flight data may not be available to investigators after an accident, increasing the risk of not being able to determine the underlying causes and advance transportation safety.

4.0 Safety action

4.1 Safety action taken

4.1.1 Wilderness Seaplanes Ltd.

As a result of the accident, Wilderness Seaplanes Ltd. took the following actions:

- All aircraft fuelling from fuel drums was suspended via an email distributed to pilots and company dispatch on 22 December 2023.

- Each Grumman G-21A Goose aircraft was equipped with a clear container suitable for collecting and examining fuel samples from the aircraft wing fuel sumps. The container was fitted with an extended handle to address the ergonomic difficulty of reaching the aircraft wing fuel sumps from the cockpit without the assistance of a 2nd person.