Crew fall overboard from rescue boat

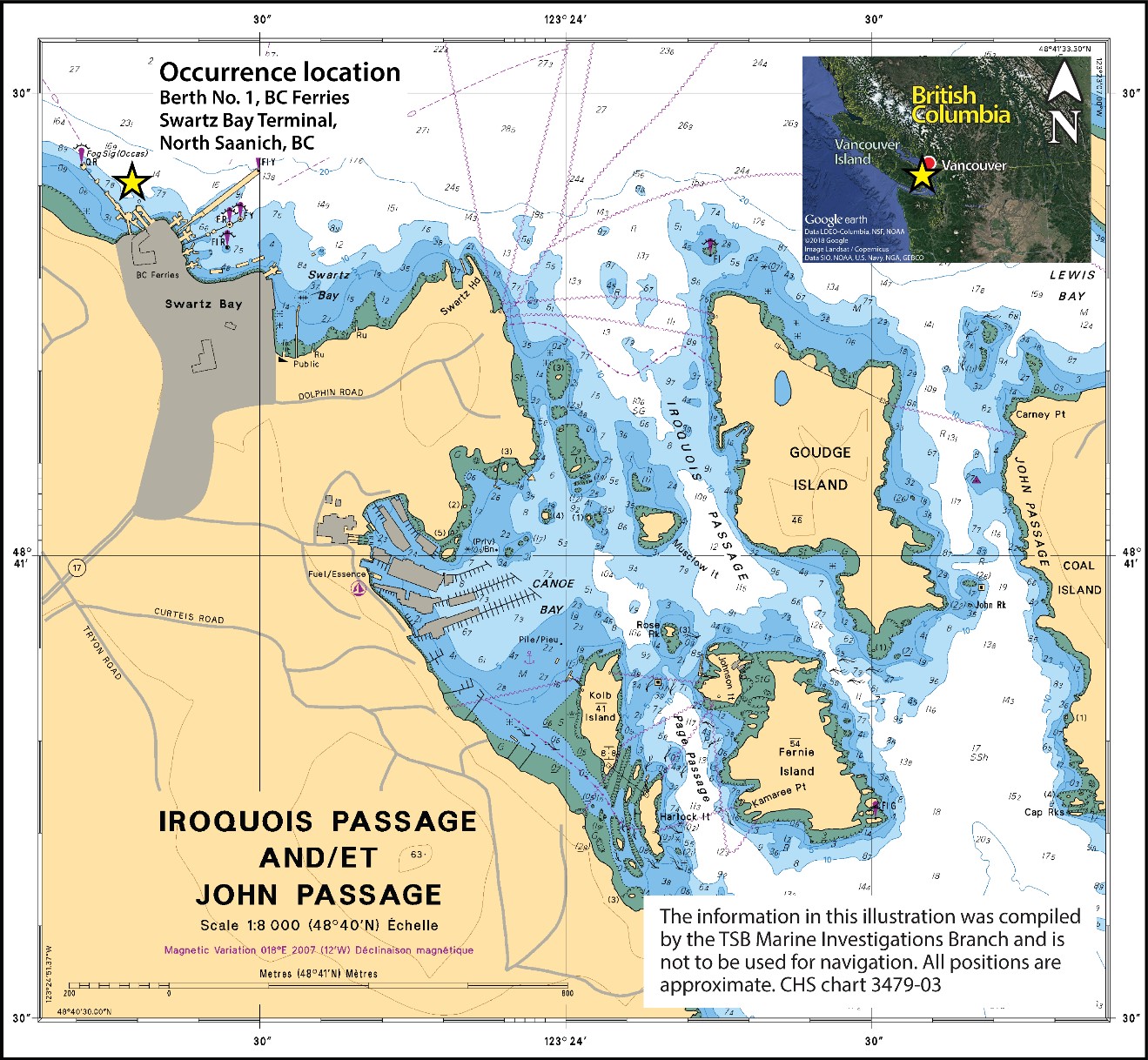

Roll-on/roll-off passenger ferry Spirit of Vancouver Island

Swartz Bay, North Saanich, British Columbia

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

On 31 August 2018, 2 crew members from the roll-on/roll-off passenger ferry Spirit of Vancouver Island fell from the vessel’s No. 1 rescue boat into the water below while participating in emergency drills at Swartz Bay Ferry Terminal in North Saanich, British Columbia. Vessel crew retrieved the 2 crew members from the water, and local emergency health services brought them to the hospital. One crew member was treated for minor injuries, the other was uninjured, and both were released later that day. The rescue boat sustained minor damage to its bottom hull.

1.0 Factual information

1.1 Particulars of the vessel

| Name of vessel | Spirit of Vancouver Island |

|---|---|

| Official number / IMO number | 816503 / 9030682 |

| Port of registry | Victoria, BC |

| Flag | Canada |

| Type | Roll-on/roll-off passenger ferry |

| Gross tonnage | 21 958 |

| Length, registered | 159.30 m |

| Built | 1993 |

| Builder | Integrated Ferry Constructors Ltd, Victoria, BC |

| Propulsion | Four 4-stroke medium speed engines, driving 2 controllable-pitch propellers (4X4000 KW) |

| Crew and passengers on board at the time of the occurrence | 44 crew, 0 passengers |

| Owner | British Columbia Ferry Services Inc. |

1.2 Description of the vessel

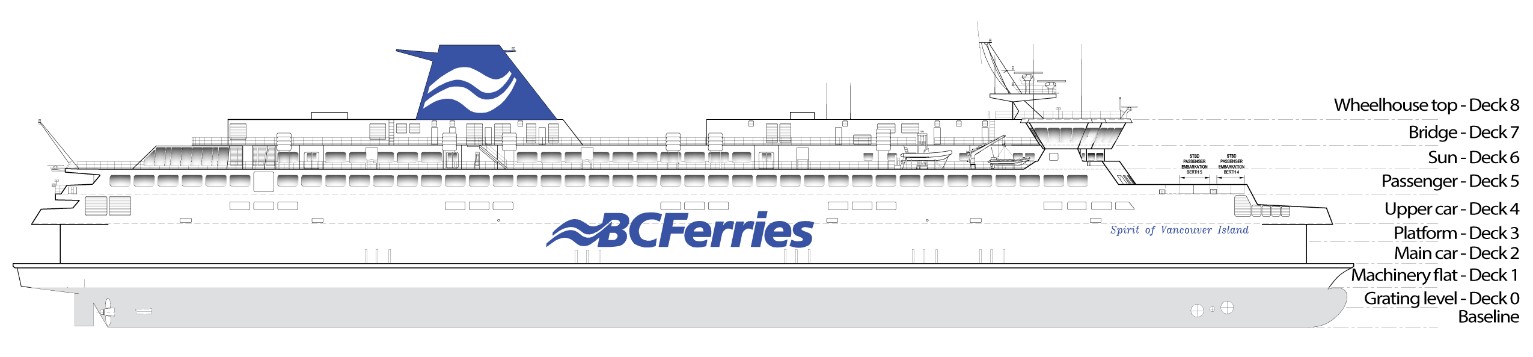

The Spirit of Vancouver Island (Figure 1) is an 8-deck, steel-hulled vessel owned and operated by British Columbia Ferry Services Inc. (BC Ferries). The vessel can carry a maximum of 2059 passengers, 470 vehicles, and 41 crew members.

The vessel’s 8 decks are arranged as follows (Appendix B):

- Deck 1: engine room

- Decks 2, 3, and 4: vehicles

- Deck 5: passengers and amenities

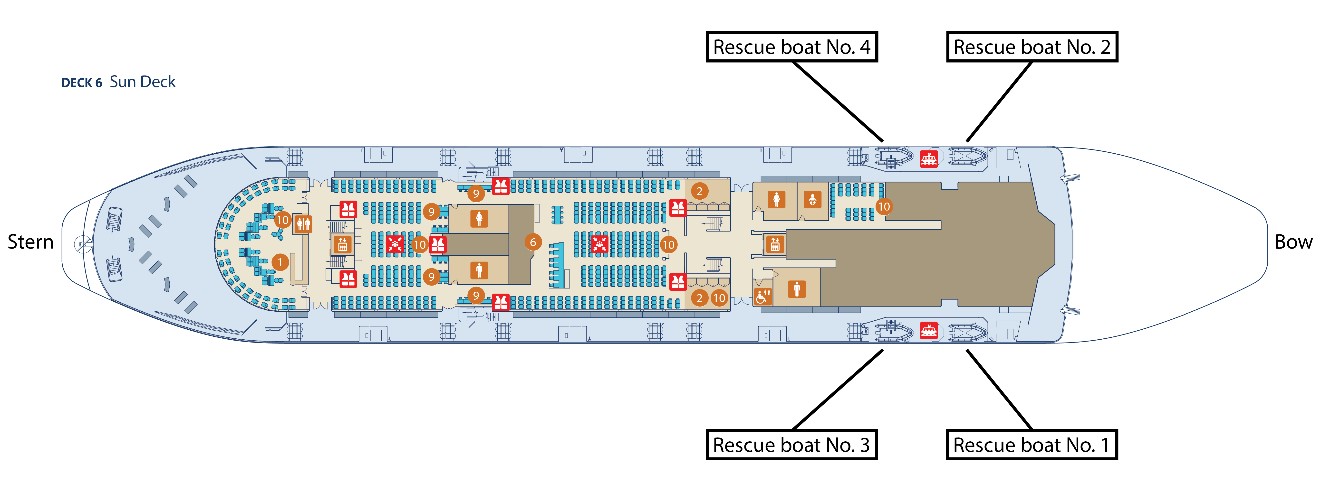

- Deck 6: sundeck for passengers, and 4 rescue boats (2 starboard, 2 port; see Figure 2). Deck 6 is approximately 14 m from the waterline.

- Deck 7: wheelhouse

- Deck 8: wheelhouse top

The wheelhouse located on deck 7 is equipped according to regulations with navigational and communication equipment, including very high frequency radiotelephones and a public address system for on-board communication.

1.2.1 Rescue boat and davit

The vessel has 4 rescue boat stations, each consisting of a rescue boat, a cradle, and a davit. Stations No. 1 and No. 2 have slewing-type davits, which are used for lifting, slewing,Footnote 1 and lowering a rescue boat. Stations No. 3 and No. 4 have luffing-type davits that, during launching, allow the rescue boats to be positioned outboard without slewing.

Rescue boat No. 1 is a rigid-hull inflatable boatFootnote 2 that weighs 1252 kg when fully equipped and with crew on board, measures 5.02 m long and 1.98 m wide, has a capacity of 9 persons, and is propelled by a single outboard gasoline engine. It is used for marshalling and towing life rafts that are deployed during an evacuation and for person-overboard rescue operations. At the time of the occurrence, the boat was located at rescue boat station No. 1, on the forward-starboard side of the vessel.

In 2016, the vessel’s original rescue boats No. 1 and No. 2 reached the end of their useful lives and were replaced with a new type of rescue boat. Their respective rescue station davits and cradles were not replaced. The original rescue boats were a flat-type rescue boat without self-righting equipment; the new rescue boats are of a different type, with a greater height due to the boats’ self-righting equipment located at the stern (Figure 3).

BC Ferries and the installer did not conduct a risk assessment to examine the impact of the new rescue boats on the stations’ original equipment and on the crews’ rescue boat operating procedures.

1.2.2 Operating the davits

The Spirit of Vancouver Island’s rescue boat station No. 1 and No. 2 davits are each equipped with a self-slewing control cable and a brake release line (Figure 4). Rescue boats No. 1 and No. 2 are designed so that they can be launched by the coxswain or the bowmanFootnote 3 on board the rescue boat using the brake release line and self-slewing control cable that run from the rescue boat to its corresponding davit. This operation is known as self-launching. Alternatively, a crew member can remain on deck to act as the davit operator, and operates the davit to launch its corresponding rescue boat. This operation is known as launching with a davit operator.

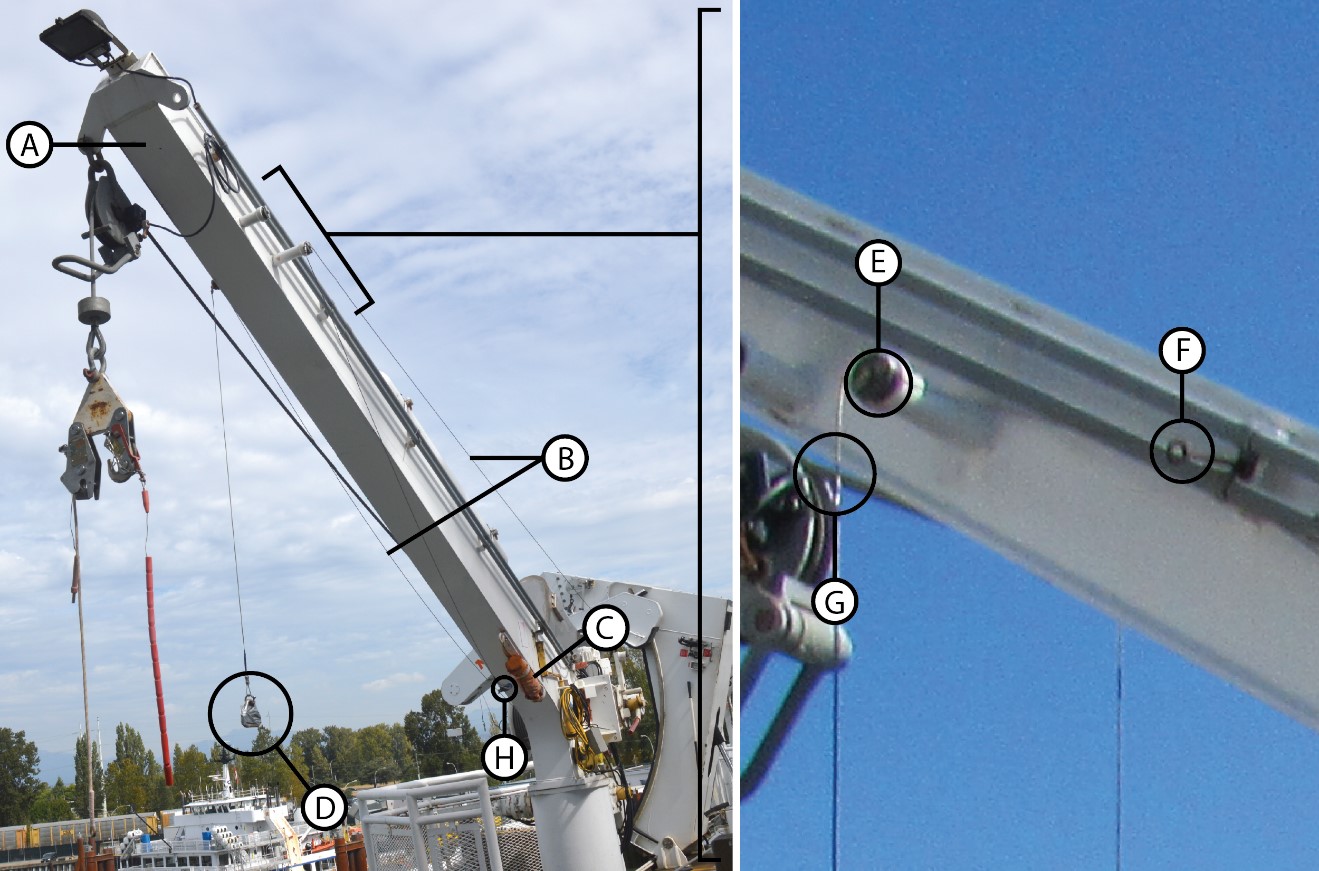

Legend

A Davit arm

B Wire rope connecting the brake release line and brake release mechanism

C Brake release line bag

D Self-slewing line

E Topmost sheave

F Eye bolt manufactured by a company other than the original equipment manufacturer

G Stopper

H Connection between brake release line and wire rope

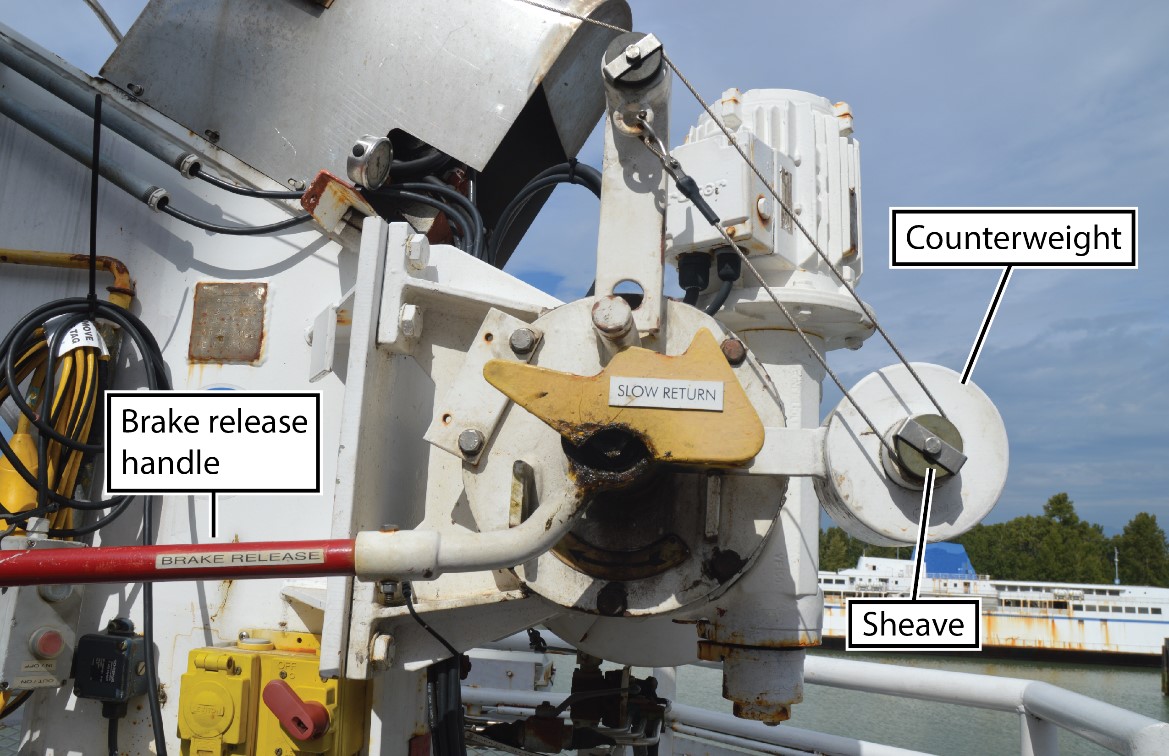

When the rescue boat is launched with a davit operator, the davit operator is positioned at the davit and slews the davit using the davit’s slewing control. The operator then releases the davit’s brake by manually raising the counterweight, or by pulling down on the davit brake release handle, which in turn raises the counterweight and releases the brake (Figure 5).

When the rescue boat is self-launched, the coxswain or the bowman in the rescue boat slews the davit by pulling the self-slewing control cable that extends from the davit to the rescue boat, and then releases the davit brake by pulling the brake release line from within the rescue boat.

1.2.3 Brake release lines

Each rescue boat’s brake release line is composed of a length of orange nylon rope connected to a wire rope. The wire rope runs inboard along the davit arm on sheaves, passes around another sheave fitted to the brake release mechanism’s counterweight, and is then secured to an eye bolt on the davit structure. When the coxswain pulls the brake release line, the counterweight lifts and releases the davit brake. Once the davit brake is released, the rescue boat will lower to the water at a rate of about 1 m per second, limited by a centrifugal brake. When the brake release line is no longer being pulled, the counterweight drops and the brake re-engages.

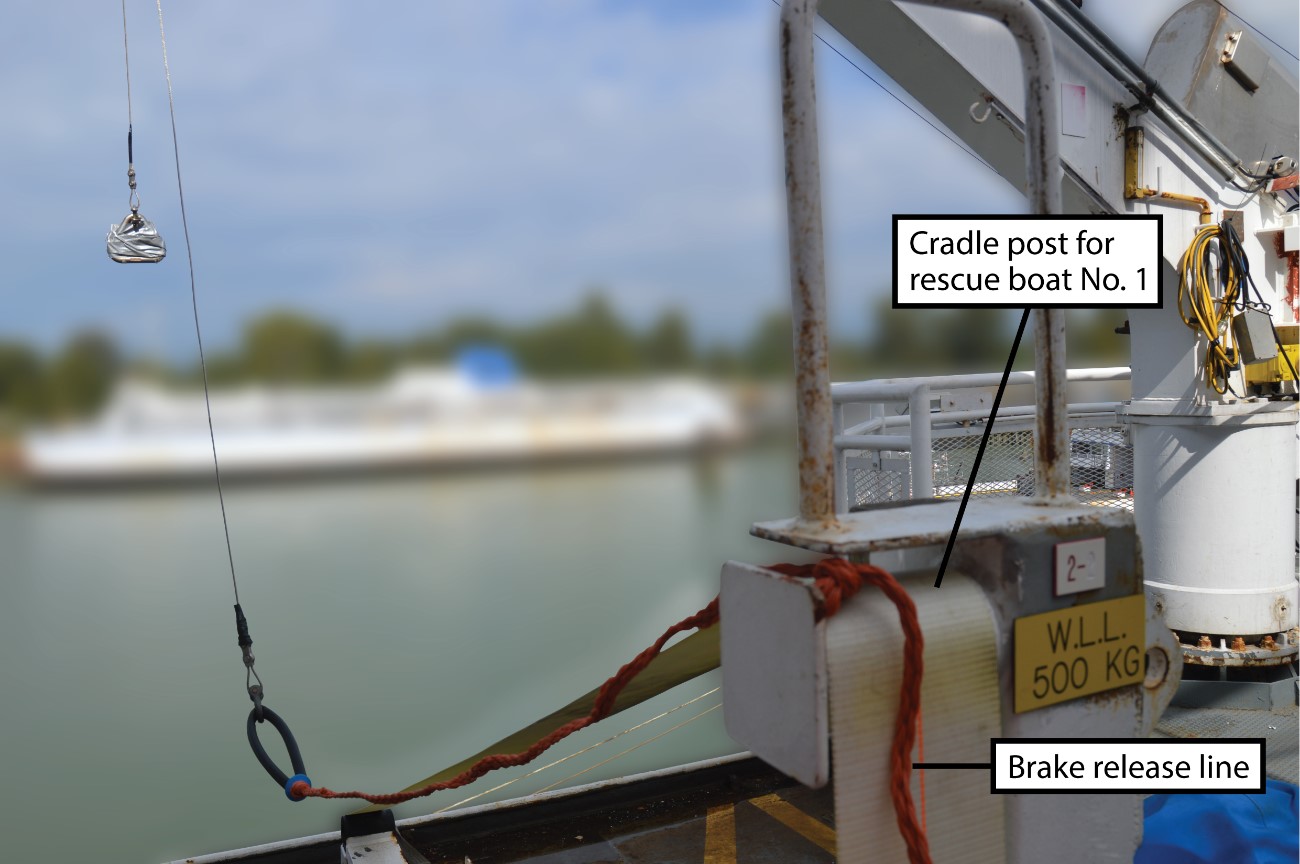

When the coxswain is on board one of the rescue boats, the coxswain’s view inboard of the cradle post and of the davit control area is partially obscured by the cradle post, the davit arm, and the deck railings.

On board the Spirit of Vancouver Island, when a davit operator uses a davit to lower a rescue boat, a crew member (usually a deckhand) coils and stores the brake release line in an orange brake release line bag. Before the rescue boats were replaced with the type used in this occurrence, crew stored each boat’s brake release line and bag under its respective davit arm, as shown in Figure 4.

When the vessel’s new rescue boats were installed, crew noticed that the brake release line on each davit was sagging along its davit arm. An eye bolt manufactured by a company other than the original equipment manufacturer was installed on each davit arm to run the brake release line through and reduce sag. There is no record that this modification was approved by the original equipment manufacturer.Footnote 4 The brake release line stopperFootnote 5 on davit No. 1 was not moved closer to the topmost sheave to accommodate the new rescue boat’s greater height.

1.2.4 Previous incidents involving the davits

During a drill conducted in May 2017, 15 months before the occurrence, rescue boat No. 2’s brake release line was sagging from its davit arm and became tangled on one of the rescue boat’s stern lights. Following this incident, BC Ferries conducted an internal review. On 12 June 2017, the Spirit of Vancouver Island’s senior master issued a directive to crew stating that the brake release lines were to be deployed (i.e., dropped into the water and allowed to float freely beside the rescue boat) every time a rescue boat was lowered to water level, and that crew should not stow brake release lines and bags on davit arms. Crew then made cylindrical containers (Figure 6) to stow the brake release lines and bags on rescue boats No. 1 and No. 2 when the rescue boats were in their stowed position; these containers were fitted to the back of a bench where the coxswain usually sits in each boat. Crew moved the brake release lines and bags for davits No. 1 and No. 2 to those containers.

Several months after the brake release lines and bags were relocated to these cylindrical containers, another incident occurred during a drill where the brake release line for rescue boat station No. 1 was deployed to the water and became tangled with rescue boat No. 1’s propeller. To prevent a recurrence of this incident, some members of the crew developed an informal and undocumented practice of not deploying rescue boat No. 1’s brake release line to the water, and instead passing the line and the bag from the rescue boat to an officer on deck when a rescue boat was launched with a davit operator. When an officer was not at a rescue boat station to receive the line and bag, crew left the line and bag on the vessel’s deck. Crew did not inform vessel management of this practice or of the incident that led to the practice.

1.3 History of the occurrence

On 31 August 2018 at 0600,Footnote 6 following a briefing from the master and chief officer, the Spirit of Vancouver Island’s crew began conducting planned boat and fire drills while the vessel was berthed at Swartz Bay Ferry Terminal. These drills were conducted before the vessel’s first voyage on that day. During the briefing, it was determined that crew would conduct 3 rescue boat drills and 1 fire drill at the same time.

In accordance with the assigned emergency duties, the master went to the bridge to oversee the drills. Two deckhands proceeded to the starboard side of deck 6 to prepare rescue boat No. 1 for launch, and the third engineer joined the deckhands shortly thereafter. The second and third officers were on deck 5 with the remaining crew members, to train them in the use of firefighting appliances. The chief officer quickly briefed the crew members assigned to rescue boat station No. 1. He then proceeded to the port-side rescue boat stations, where he was the officer in charge of supervising the preparation and launching of rescue boats No. 2 and No. 4.

Because no deck officer was present at rescue boat station No. 1, 1 of the 2 deckhands assigned to that station assumed the responsibility of acting as the coxswain while the other acted as the bowman. The third engineer, who had been delegated by the chief officer to attend rescue boat station No. 1, arrived later at the station and acted as the davit operator.

At about 0616, the coxswain and the bowman completed BC Ferries’ At the Station Checklist. Both crew members acknowledged and confirmed each item on the checklist. They also checked the brake release line bag containing the brake release line.

The coxswain and bowman each donned the required personal protective equipment, boarded rescue boat No. 1, and placed the brake release line bag on deck 6. The coxswain and bowman completed BC Ferries’ In the Boat Checklist, and then signalled the davit operator to raise the boat. Using the davit’s controls, the davit operator began raising the rescue boat from its cradle. At this time, the master arrived at rescue boat station and observed the rescue boat being raised. With sufficient clearance from the cradle, the coxswain pulled the self-slewing lineFootnote 7 hanging above the rescue boat to slew the davit arm outboard. While slewing, approximately 15 cm of brake release line uncoiled from the brake release line bag on deck. The brake release line snagged on a vertical section of the cradle post, creating tension on the brake release line (Figure 7).

As the davit arm slewed further outboard, the rescue boat suddenly dropped, and the bottom of its port side hull hit the raised edge of the vessel’s outboard deck. The rescue boat tilted outboard to such a degree that the coxswain and bowman fell from the boat. The coxswain fell approximately 14 m into the water below, while the bowman grabbed hold of the rescue boat’s painter line approximately 4 m above the water. The rescue boat continued its descent toward the water as the bowman held on to the painter. Eventually, the bowman let go of the painter and dropped approximately 2 m into the water. The rescue boat reached the water level soon after.

The master broadcast a person-overboard call throughout the vessel via the vessel’s public address system, and to the rescue boats via very high frequency radiotelephone. Rescue boat No. 4 was already on the water on the vessel’s port side. The crew on board responded to the call by bringing the boat around the vessel’s bow to rescue boat No. 1 and retrieving the bowman and coxswain. When the bowman and coxswain were returned to the vessel, they received first aid from the vessel’s first aid attendant. The bowman and coxswain were brought to a local hospital by emergency health services and were released later that day. The coxswain sustained minor injuries; the bowman was not injured.

1.4 Damage to the rescue boat

The rescue boat’s bottom hull sustained minor damage around the port keel area due to the impact with the edge of the outboard deck.

1.5 Environmental conditions

The weather at the time of the occurrence was clear with good visibility of more than 15 nautical miles (NM). According to Environment and Climate Change Canada’s hourly data report at the nearest weather station (Victoria International Airport), there was a west-southwesterly wind of 5 knots with an air temperature of 13 °C and a water temperature of about 16 °C.

1.6 Vessel certification and survey

The Spirit of Vancouver Island carried all of the required certificates issued by Transport Canada (TC), and the American Bureau of Shipping on behalf of TC, for a vessel of its class and for the intended voyage. As delegated by TC, the American Bureau of Shipping, a recognized organization,Footnote 8 conducted the vessel’s last annual inspection on 13 February 2018, and its last 5-year (renewal) inspection on 27 February 2017.

1.7 Personnel certification and experience

The master held a Master, Near Coastal Certificate of Competency that was first issued in 2003, was last renewed on 22 July 2016, and is valid until 21 July 2021. He had worked with BC Ferries for approximately 26 years, including 13 years as a master on various BC Ferries vessels. He began working on board the Spirit of Vancouver Island as a master in 2007. He was familiarized with the vessel before assuming the role of master.

The chief officer held a Chief Officer, Near Coastal Certificate of Competency that was renewed on 26 April 2016. He joined BC Ferries in 1978 as a deckhand and retired from the company in 2017 as chief officer. He rejoined BC Ferries as a casual deck officer 6 weeks after his retirement. He was familiarized with the Spirit of Vancouver Island before assuming the role of chief officer.

The coxswain joined BC Ferries in 2007 and began working as a casual deckhand in 2008. After working 6 months as a casual deckhand, he became a regular deckhand. He has worked on the Spirit of Vancouver Island since 2013. He had completed TC-approved Marine Emergency Duties (MED) courses including Proficiency in Survival Craft and Rescue Boats Other Than Fast Rescue Boats, . He also held a Restricted Operator’s Certificate-Maritime Commercial (ROC-MC). He was familiarized with the vessel before assuming the role of deckhand. The bowman joined BC Ferries in 2001 and took training as a deckhand in 2011. He joined the Spirit of Vancouver Island as a deckhand in 2014. He had completed TC-approved MED courses including Proficiency in Survival Craft and Rescue Boats Other Than Fast Rescue Boats, and was familiarized with the vessel before assuming the role of deckhand.

The third engineer held a Fourth-Class Engineer, Motor Ship, Certificate of Competency issued in 2018. He began his career as a marine engineer in 1991, and worked on various types of vessels before he joined BC Ferries in 2008. He completed MED courses in 2009, including Proficiency in Survival Craft and Rescue Boats Other Than Fast Rescue Boats. He also completed his familiarization training, which included rescue boat launch, as a third engineer in 2017 on the Spirit of Vancouver Island. This occurrence was the first time the third engineer had operated a slewing davit.

1.8 Safety management systems

The main objective of a safety management system (SMS) is the safe operation of a vessel to ensure the safety of crew and passengers, and to avoid damage to property and the environment. An SMS involves individuals at all levels of an organization and promotes a logical approach to hazard identification, risk assessment, and mitigation. It includes a set of documents that a vessel owner or authorized representative prepares with their masters and crew to establish procedures, plans, and instructions, including checklists as appropriate.

The International Safety Management Code (the ISM Code),Footnote 9 provides an international standard for the safe operation of ships and pollution prevention. Chapter IX of the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea, 1974 requires certain ship operators to comply with the ISM code.

Presently, 3 types of Canadian vessels that operate on international voyages must adopt an SMSFootnote 10 that complies with the ISM code:

- Passenger ships, including passenger high-speed craft;

- Oil tankers, chemical tankers, gas carriers, bulk carriers and cargo high-speed craft of 500 gross tonnage and upwards; and

- Other cargo ships and mobile offshore drilling units of 500 gross tonnage and upwards.

TC is in the process of amending Canada’s Safety Management Regulations. When these proposed amended regulations come into force, in addition to the vessel types mentioned above, Canadian vessels with a gross tonnage of more than 500, Canadian vessels that carry more than 50 passengers, Canadian vessels that are greater than 24 m and less than 500 gross tonnage, and the companies that operate them, will be required to adopt an SMS in compliance with the ISM code.Footnote 11

Under current Canadian regulations, the Spirit of Vancouver Island is not required to have an SMS, but the vessel and BC Ferries voluntarily adopted an SMS that complies with the ISM Code.

1.9 Familiarization and training

BC Ferries uses a web-based program known as Standardized Education and Assessment (SEA) to familiarize employees, train them, and test their competence before authorizing them to work on company vessels.

The SEA program uses a blended learning approach that includes online learning and examinations as well as trainer-led face-to-face learning and hands-on practice for equipment operation. During training, crew are instructed to report any unsafe act or unsafe condition that they witness on their vessel to the vessel officer, the vessel’s senior management, or BC Ferries. Reports can be made verbally or in writing, such as through the All Learning Events Reported Today (ALERT) system and Initial Assessment Reports.

BC Ferries also requires any crew member who is assigned rescue boat duties to have completed a TC-approved Proficiency in Survival Craft and Rescue Boats other than Fast Rescue Boats (PSC) course. Topics covered in the course include introduction and safety, principles of survival, evacuation, actions to take when aboard a survival craft, launching arrangements, and drills for practice in launching and recovering.Footnote 12 At least 1 crew member in each rescue boat must also have, at minimum, a Restricted Operator’s Certificate-Maritime Commercial (ROC-MC). The course covers several communication topics including standard radio communication practices.

In addition to the PSC course, BC Ferries also requires the coxswain or person in charge of a rescue boat to complete the BC Ferries’ Shepherd Boat Training Course. The course is designed to provide background knowledge and skills in safe rescue/shepherd boat operations.

Prior to this occurrence, the Spirit of Vancouver Island’s third engineer, bowman, and coxswain underwent the SEA program. The coxswain had also completed BC Ferries’ rescue/shepherd boat training course.

1.10 Emergency drill planning and execution of drills

The crew of the Spirit of Vancouver Island had not conducted a rescue boat drill with crew members on board a rescue boat since April 2018, when a Fleet Operations Directive was issued that restricted the use of rescue boats to emergencies only. This restriction was removed in a second Fleet Operations Directive issued on 13 July 2018.Footnote 13 In response to this second directive, on 30 August 2018, the master and the chief officer planned fire and boat drills to familiarize crew with and train them on how to launch rescue boats, as well as to demonstrate the use of firefighting appliances.

In accordance with BC Ferries’ Fleet Operations Manual, crew perform fire and rescue boat drills once a month.Footnote 14 Resources are allocated for drills at the discretion of the master and chief officer. Typically, a full complement of crew performs these drills sequentially; they conduct the fire drill first, then proceed to the vessel’s rescue boat stations to launch as many rescue boats as needed according to the boats’ required launch schedule.Footnote 15 If more than one boat must be launched, the boats are launched at the same time or one at a time, depending on the availability of officers in charge to supervise. There is no requirement in the Fleet Operations Manual for rescue boats to be launched concurrently.

In this occurrence, to compensate for the 4-month gap in testing during the emergency-use-only restriction, and to save time and resources, the master and chief officer planned to conduct a fire drill and 3 rescue boat drills at the same time prior to the first voyage of the day. During the rescue boat drills, the chief officer supervised rescue boat stations No. 2 and No. 4. After the initial briefing no officer was present at rescue boat station No. 1 to perform the duties of officer in charge.

1.11 Delegation of officer-in-charge duties

BC Ferries’ Fleet Operations Manual stated that where the availability of resources permits, the officer in charge of launching a rescue boat should avoid acting as the coxswain in the rescue boat or taking an active role in the launch operations.Footnote 16 Taking an active role in rescue boat launch operations restricts a person’s ability to perform effective oversight of the overall operation, because the person’s attention is focused on the task at hand. Humans can process only one task at a time, continuously alternating attention between tasks. Multi-tasking may lead to a decrease in performance on each task.Footnote 17

BC Ferries’ Spirit Class Specific Manual stated that if no officer on deck (OOD) is available, the coxswain can assume the duties of an officer in charge.Footnote 18 The provision applies only in case of emergency and only if no other officer is available; it does not apply to regular operations or routine drills. This distinction is not described in any manual or directives, nor was it explained verbally to crew or officers.

In July 2018, a Fleet Operations Directive had been issued that contained an update to the BC Ferries’ Rescue Boat Checklists and Procedures found in the Fleet Operations Manual. This directive stated that the coxswain could assume the duties of an officer in charge when there is none available. At the time of the occurrence, this update had not been incorporated into the Spirit Class Specific Manual and Fleet Operations Manual and this information was not known to the crew. In this occurrence, the chief officer was occupied with supervising the launch of rescue boats No. 2 and No. 4 on the vessel’s port side. The coxswain for rescue boat station No. 1 performed his duties as coxswain in addition to assuming the responsibilities of the officer in charge for that station. The third engineer was tasked by the coxswain with raising rescue boat No. 1 from its cradle, acting independently for the first time as the station’s davit operator.

1.12 Workload and the chief officer’s duties during drills

Workload is a function of the number of tasks that must be completed within a given amount of time. If the number of tasks that must be completed increases, or if time available decreases, workload increases.Footnote 19 In the context of an emergency fire and boat drill, crew operate in a dynamic environment where there are multiple sources and types of information to assess and keep track of. In a time-critical situation, workload can lead to human error or delayed decisions to accommodate the processing of relevant information.

Workload may also be defined as the demand for resources.Footnote 20 People operating under conditions of high or very high workload can become task-saturated or overloaded, and may channel their attention, concentrating on some tasks at the expense of others.

Per the vessel’s muster list and BC Ferries’ Spirit Class Specific Manual, Footnote 21 the chief officer’s duties during a fire and boat drill require activities such as supervision, decision making, allocating work, and communications to be carried out at the same time. These duties include, but are not limited to,

- coordinating the emergency drill

- diagnosing the simulated fire, which entails simultaneously deciding, acquiring new information, carrying emergency equipment, allocating tasks to crew members, communicating with crew members in person and remotely, moving to different areas on board the vessel, preparing the vessel for a possible evacuation

- coordinating an evacuation once the evacuation alarm is sounded, which includes planning for the evacuation, moving to different areas, allocating tasks to crew members, in-person and remote communication

- supervising and carrying out the simulated evacuation as deck officer in charge

1.13 Documentation for BC Ferriesrescue boat launch and recovery procedures

The Spirit Class Specific ManualFootnote 22 includes procedures for launching and recovering rescue boats No. 1 and No. 2, with a davit operator and when self-launching (where a davit operator is not required)

The Fleet Operations Manual, which applies to all BC Ferries vessels, includes a standard procedure stating that before launching a rescue boat during a drill, all crew must receive a safety briefing from the officer in charge. The officer must ensure that the appropriate checklists from the Fleet Operations Manual and Spirit Class Specific Manual are completed under the officer’s supervision.

The procedures in the Spirit Class Specific Manual also describe launching and recovering rescue boats with their brake release lines and bags stowed on the davit arm of each rescue boat station; the Spirit Class Specific Manual was not updated when the stowage location for the brake release lines and bags changed from the davit arm to the cylindrical containers behind the coxswain’s bench.

In addition to the Spirit Class Specific Manual, a Senior Master DirectiveFootnote 23 specific to the Spirit of Vancouver Island states that when launching rescue boats No. 1 and No. 2 with a davit, the brake release line and bag should be deployed (dropped into the water) every time the boats are lowered to water level. The brake release lines and bags should not be stowed on any davit arm. When crew are self-launching rescue boats No. 1 and No. 2, the procedures in the Spirit Class Specific Manual state that the brake release line should be accessible and the brake release line bag should be in the rescue boat.Footnote 24 No manual or directive indicates that the brake release line and brake release line bag should be left on deck.

1.14 Rescue boat checklists

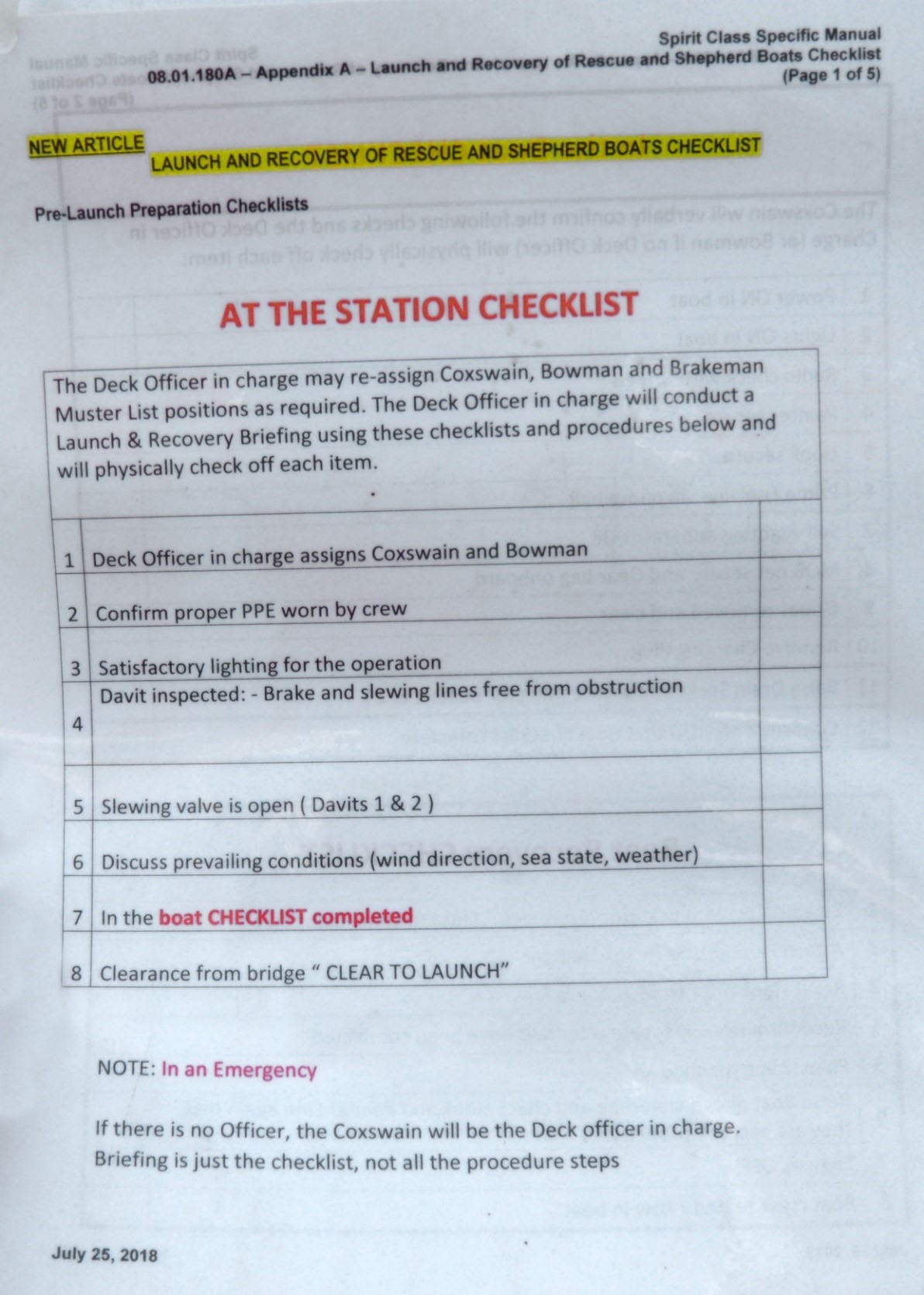

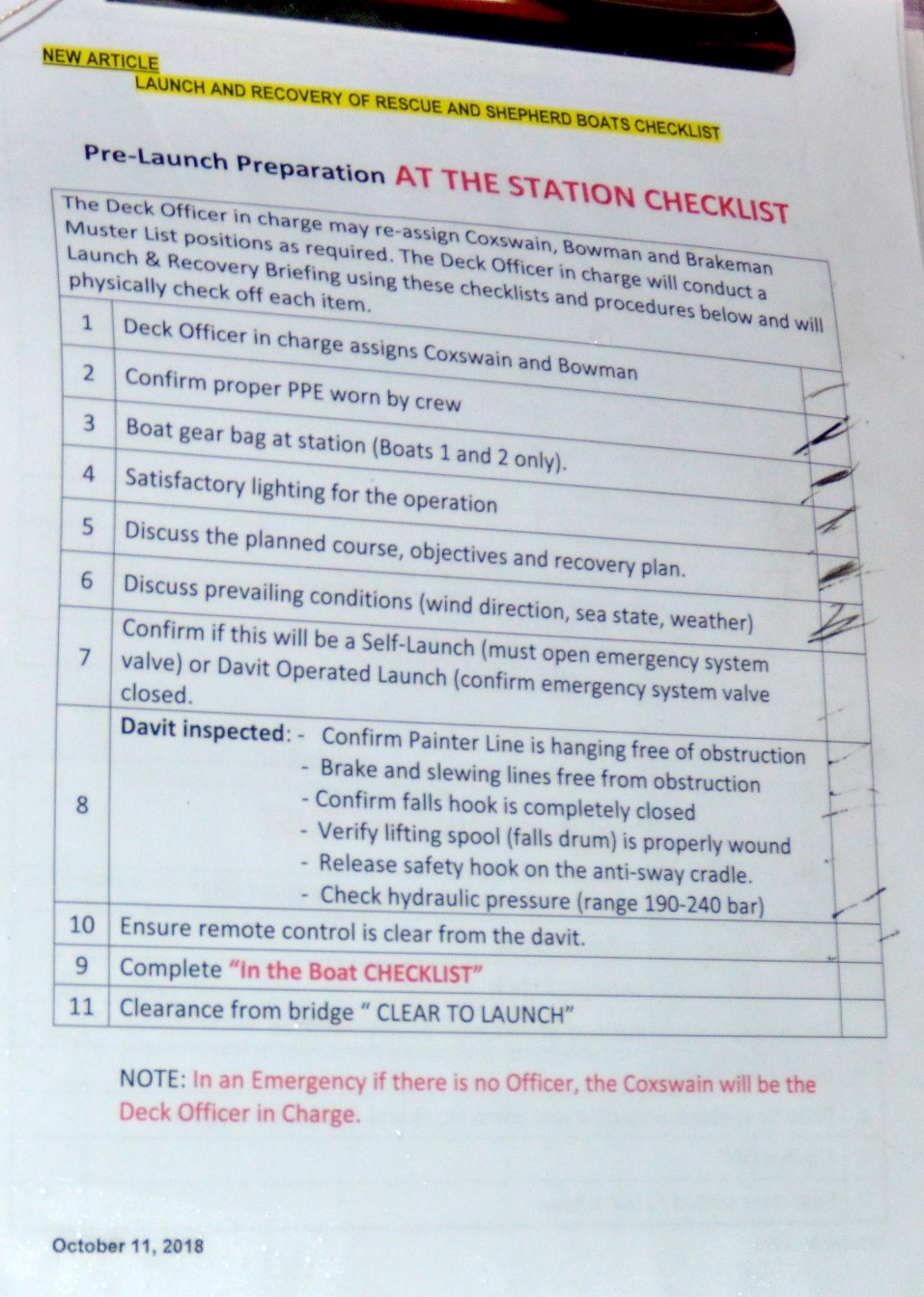

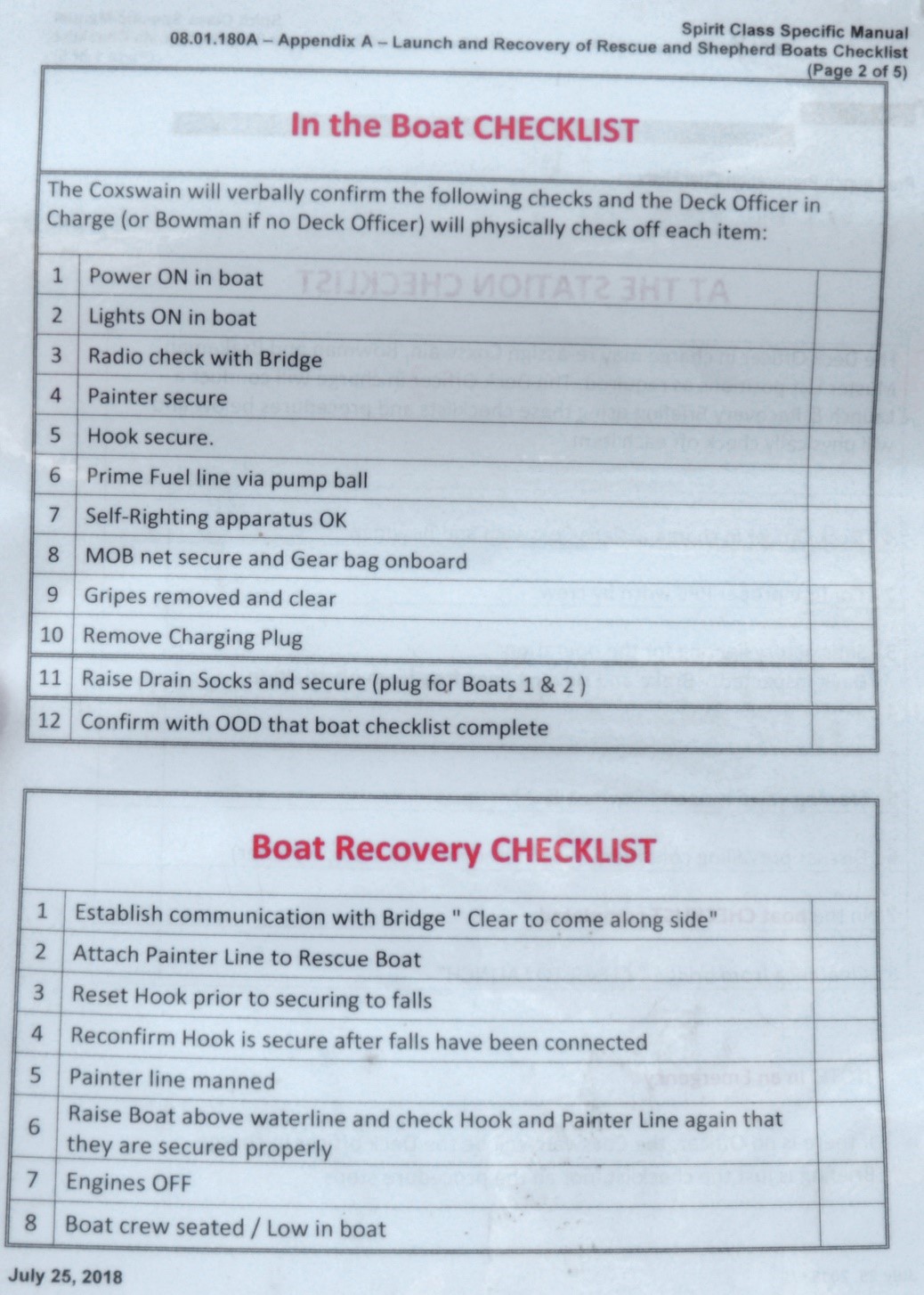

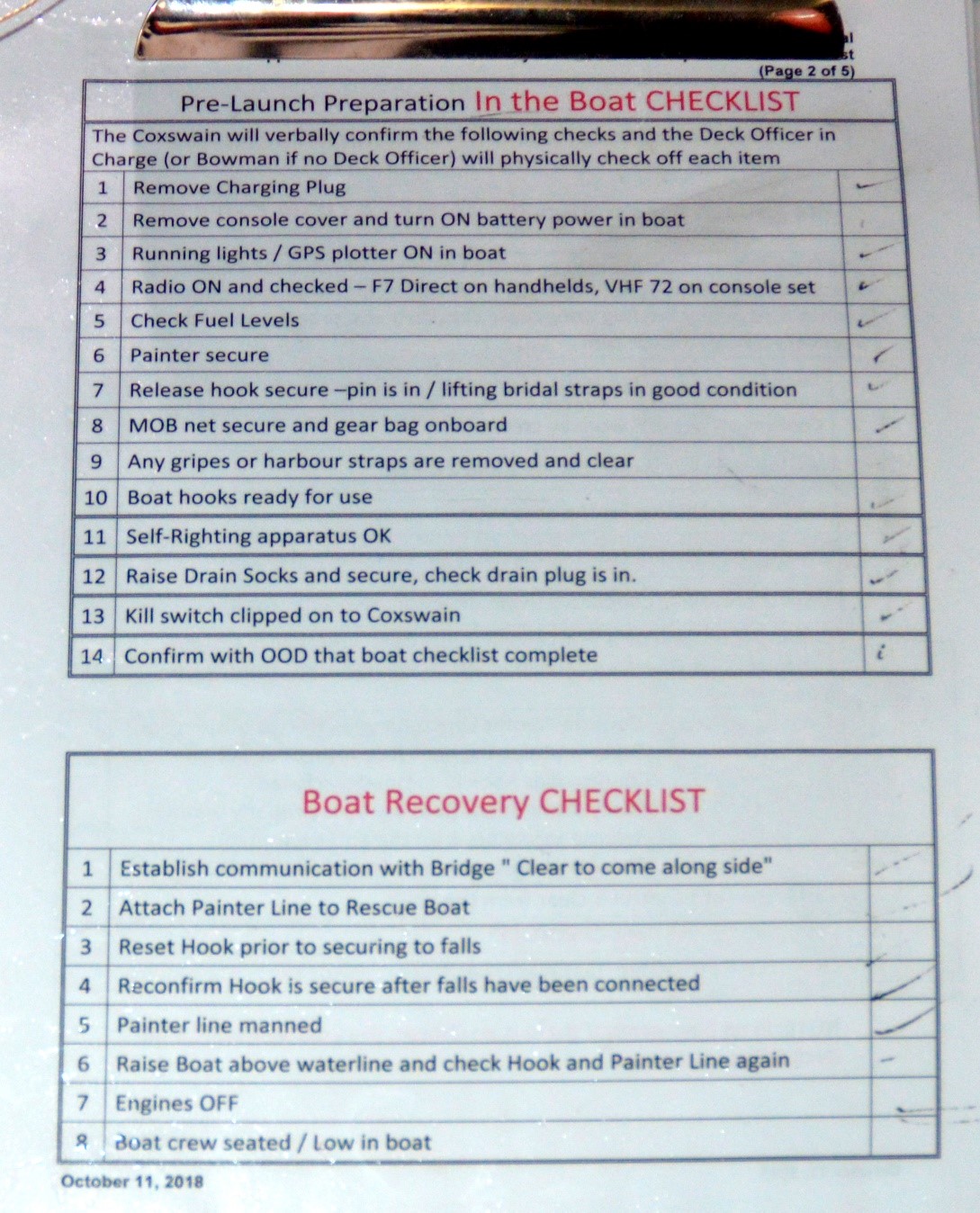

On 13 July 2018, BC Ferries issued a Fleet Operations Directive that updated the following checklists in its Fleet Operations Manual: At the Station Checklist, In the Boat Checklist, and Recovery Checklist. These checklists outline steps for launching and recovering rescue boats.

On 25 July 2018, the Spirit of Vancouver Island partially updated its At the Station (Appendix C), In the Boat, and Recovery (Appendix D) checklists, as per the Fleet Operations Directive. The checklist items remained the same, and a note about officers in charge of rescue boat stations was added to the bottom of the At the Station Checklist. Overall, the vessel’s checklists significantly differed from the checklists issued in the Fleet Operations Directive in terms of task terminology and number of steps. Table 2 presents the number of steps found in each checklist.

| Checklist | Fleet Operations Directive | Laminated checklist at the rescue boat stations |

|---|---|---|

| At the Station Checklist | 14 steps | 8 steps |

| In the Boat Checklist | 14 steps | 12 steps |

| Recovery Checklist | 4 steps | 8 steps |

The Spirit of Vancouver Island’s Senior Master Directive 005, issued 02 August 2018, includes the following requirements for launching a rescue boat:

- The officer in charge must go through the checklist with the rescue boat crew and davit operator to make sure the station is cleared for launching.

- All watches must familiarize their crew with these checklists and procedures before commencing rescue boat operations.Footnote 25

Before a rescue boat is launched, operators must complete the At the Station Checklist and then the In the Boat Checklist, located at each rescue boat station. The operator physically checks off each procedure item on the list as it is completed. The operator confirms completion of each step through observation and verbal confirmation with another crew member who is assigned to the same rescue boat.

Crew are typically informed of updates or changes to BC Ferries manuals during monthly meetings. In this case, crew were informed about the updates to the rescue boat launch and recovery checklists on the day of the occurrence, during the master and chief officer’s briefing before the fire and rescue boat drills.

The checklists located at the rescue boat stations did not take into account the differences between self-launching procedures and launching procedures involving a davit operator, nor did the checklists distinguish between station No. 1 and No. 2 slewing davits and station No. 3 and No. 4 luffing davits.

As there was no deck officer present, the coxswain and the bowman completed the available checklists just prior to the arrival of the third engineer.

1.15 Post-occurrence examination

Following the occurrence, TSB investigators visited the occurrence vessel where they checked the vessel’s davit and rescue boat equipment. The following items were identified during the TSB’s visit:

- There was a knot in the brake release line approximately 1 to 2 m from where the brake release line connects to a wire rope for the brake release mechanism.

- A non-original equipment manufacturer eye-bolt was installed on each davit to minimize brake release line sagging.

- The stopper on the brake release line was located approximately 70 mm from the third sheave, which allowed slack on the brake release line.

The TSB investigators also visited its sister vessel, the Spirit of British Columbia, and identified that the brake release line bag, with its line secured inside, was stowed in its original location, underneath the davit arm. TSB investigators also observed a fire and rescue boat drill to understand the BC Ferries’ emergency procedures.

1.16 TSB Watchlist

The TSB Watchlist identifies the key safety issues that need to be addressed to make Canada’s transportation system even safer.

Safety management and oversight is a Watchlist 2018 issue. As this occurrence demonstrates, BC Ferries’ SMS did not identify hazards related to changing the rescue boat type, procedures for the stowage of the brake release line bag, and supervision of rescue boat operations. Footnote 26

ACTIONS REQUIRED

Safety management and oversight will remain on the Watchlist until:

- Transport Canada implements regulations requiring all commercial operators in the air and marine industries to have formal safety management processes, and effectively oversees these processes.

- Transportation operators that do have an SMS demonstrate to Transport Canada that it is working—that hazards are being identified and effective risk-mitigation measures are being implemented.

- Transport Canada not only intervenes when operators are unable to manage safety effectively, but does so in a way that succeeds in changing unsafe operating practices.

2.0 Analysis

The analysis will look at the factors leading to the crew members’ fall from the rescue boat; the vessel’s safety management system; risk assessment for changes to safety critical equipment; reporting non-conformities; emergency drill planning and checklists; and the responsibilities and workload of certain crew members involved in the occurrence.

2.1 Factors leading to the fall of the rescue boat with crew on board

New rescue boats on the Spirit class vessels had been installed that were of a greater height than the original rescue boats. However, the configuration of the brake release lines for the rescue boats was not adjusted to accommodate the new rescue boats, allowing the brake release line to sag under each davit arm. Following an incident in which a rescue boat’s brake release line became entangled on the rescue boat’s stern light, the senior master of the Spirit of Vancouver Island issued a directive to have the brake release lines and their bags stored in a container on board the rescue boat instead of under the davit arms.

Several months later, the brake release line for rescue boat No. 1 became entangled with the rescue boat’s propeller during a drill. In response to this incident, some members of the crew developed an informal practice of removing rescue boat No. 1’s brake release line bag from its onboard storage container and leaving it on the deck when the rescue boat was launched with a davit operator and no deck officer was present to receive the bag. This practice was contrary to the directive issued by the senior master.

In this occurrence, rescue boat No. 1 was launched with a davit operator. When the crew removed the brake release line bag from the rescue boat, no deck officer was present to take the bag from the crew; it was therefore left unattended on the deck.

Once the bowman and coxswain had boarded the rescue boat and signalled the davit operator, the operator used the davit to raise the rescue boat from its cradle. While the davit operator raised the rescue boat, the master acted as an observer. The coxswain then started slewing the davit arm outboard.

While the davit arm was slewing, the brake release line uncoiled from the brake release line bag on deck and snagged on the cradle post, likely because of a knot in the line located approximately 1 to 2 m from where the brake release line connected to a wire rope for the brake release mechanism. The snag created tension on the brake release line that increased as the davit arm slewed further outboard, to the point that the davit brake released.

Once the davit brake released, the rescue boat dropped suddenly, and the bottom inboard hull of the rescue boat hit the edge of the deck of the Spirit of Vancouver Island, causing the rescue boat to tip outboard. The coxswain and bowman fell from the rescue boat. The coxswain fell approximately 14 m into the water. The bowman held on to the painter line; when he let go of the line, he fell approximately 2 m into the water.

2.2 Safety management system

Based on the International Safety Management Code, a safety management system (SMS) has as its main objective the safe operation of a vessel to ensure the safety of crew and passengers, and to avoid damage to property and the environment. Key components of an SMS are risk assessment for identifying hazards;Footnote 27 effective communication between all levels of a marine organization and especially between crew and senior management to ensure that non-conformities, accidents, and hazardous situations are reported;Footnote 28 proper planning for executing drills;Footnote 29 and providing safe operating procedures to the crew, including valid checklists for operating safety equipment.Footnote 30

2.2.1 Risk assessment for changes in safety equipment

Risk assessment is a process through which a company identifies hazards that have the potential to cause harm, and analyzes and evaluates the risk associated with those hazards. When rescue boat stations No. 1 and No. 2 were fitted with new rescue boat types, neither BC Ferries nor the boat installer conducted an assessment regarding the impact of the new rescue boats’ greater height on the rescue boat stations’ existing equipment. Without a proper hazard assessment, BC Ferries and crew were not aware of the potential risks posed by the new rescue boat type, such as the fact that sagging brake release lines on davits No. 1 and No. 2 posed a risk of entanglement.

Similarly, neither BC Ferries nor the Spirit of Vancouver Island’s senior management conducted an assessment to identify the potential hazards of moving the brake release line bags for rescue boat stations No. 1 and No. 2 from under the davit arms to the cylindrical containers in the rescue boats, which differs from the davit manufacturer’s original stowage location under the davit arm. This move required crew to deploy the brake release line bag of rescue boat No. 1 and No. 2 every time the boats were lowered to the water, increasing the risk of the brake release line becoming entangled in one of the boat’s propellers, as occurred with rescue boat No. 1 during a drill.

This second entanglement incident prompted the crew to develop an informal practice of leaving the brake release line bag on deck during rescue boat drills involving a davit operator.

An initial hazard assessment likely would have identified whether or not moving the stowage location of the brake release line bag introduced additional hazards and risks.

2.2.2 Reporting non-conformities

Before this occurrence, crew members on board the Spirit of Vancouver Island developed an informal practice of leaving rescue boat station No. 1’s brake release line bag on the vessel when rescue boat No. 1 was launched with a davit operator. When a deck officer was supervising the station, the brake release line bag was passed from the rescue boat to the officer on deck. If no officer was present, crew would leave the brake release line bag on the deck, inboard of the cradle post.

This practice deviated from the standard order issued in BC Ferries’ Senior Master Directive. According to the directive, the brake release line bags for rescue boat stations No. 1 and No. 2 should have been deployed (dropped in the water and allowed to float freely) while each boat was launched.

Despite crew having access to several reporting tools, such as All Learning Events Reported Today (ALERT), and the Initial Assessment Report, the practice of leaving the brake release line bag on deck and its rationale were not communicated to the vessel’s senior management, such as the senior master or senior chief engineer. Because senior management was not aware of the informal practice, it could not take steps to stop it or eliminate the potential risks or hazards associated with it.

2.2.3 Emergency drill planning

The master and chief officer planned to conduct the fire and boat drills simultaneously instead of sequentially. The emergency drill plan did not consider the availability of an officer to supervise rescue boat station No. 1. By launching 3 rescue boats at once while conducting a fire drill, the second and third officers were not available to assist the chief officer with his duties in supervising all rescue boat stations. The emergency drill plan also did not take into account individual crew member qualifications for certain tasks. Although the third engineer was familiarized with how to operate davit No. 1, he had never operated this type of davit before this occurrence.

Because resources were not sufficiently allocated for this drill, the work plan and task allocation compromised the drill’s effectiveness and the crew’s ability to fully perform their duties in case of emergency.

The decision to launch the rescue boats simultaneously was influenced by the requirement that each boat be put in the water at least once every month. Launching the 3 rescue boats at once allowed crew to meet the schedule requirement while saving time and resources. The decision was also influenced by the fact that the drill was conducted before the vessel’s first voyage of the day, which created a time urgencyFootnote 31 among crew to resume normal vessel operations.

2.2.4 Rescue boat checklists

Checklists help operators use vessel equipment and serve as a guide for conducting vessel operations. They also guide operators through new or unfamiliar tasks and can help standardize operations. Text used in checklists must be specific and unambiguous to support operators.

The Spirit of Vancouver Island uses launching and recovery checklists that are designed for BC Ferries’ 2 Spirit-class vessels. These checklists are not vessel-specific; they do not reflect the Spirit of Vancouver Island’s actual rescue boat launching systems, equipment, locations, and work practices. For example, although the vessel uses different types of davits (slewing and luffing) to launch and recover rescue boats, the checklists for launching and recovery did not take into account the different types of davit.

Working without job aids that accurately reflect the differences between rescue boat launching systems and crew’s actual on-board work practices creates a risk of error in launching and recovery operations. When operators are not provided with job aids that are specific to the operating equipment in use, operating practices may compromise the safety of vessel operations.

If key components of a safety management system, such as risk assessments, reporting non-conformities, emergency drill planning, and valid checklists are not put into practice by companies and crews, there is a risk that the safety of passengers and crew will be compromised.

2.3 Chief officer’s workload

A chief officer’s role and responsibilities during emergency operations require the chief officer to perform tasks such as supervision, decision making, and communication concurrently. In this instance, these tasks and the conditions under which the emergency drill took place did not support the chief officer’s effective performance, as other officers were delegated to other tasks and unavailable to assist. The following safety-relevant conditions were identified during the investigation:

- The supervision of davits and rescue boats required the physical presence of the chief officer at each station; however, stations No. 1 and No. 3 are located on the starboard side of deck 6, and stations No. 2 and No. 4 are located on the port side. It was physically impossible for the chief officer to attend to opposite sides of the vessel at the same time.

- The chief officer was required to physically check off items on the At the Station and In the Boat checklists for each rescue boat, which significantly reduced his oversight abilities.

- The chief officer was operating under time constraints. There was time urgency to return to normal operations, and there was time pressure induced by the nature of the emergency drill itself.

In this occurrence, the chief officer experienced a high workload in which he had to attend to multiple tasks and he was not available to supervise at rescue boat station No. 1.

If the duties of a chief officer during emergency drills require them to attend to multiple tasks under high workload, there is a risk that the emergency response will be inadequate.

2.4 Duties of the officer in charge for rescue boat stations

In this occurrence, the second and third officers were assigned to oversee the firefighting equipment demonstration on deck 5. The emergency drill plan required the 3 rescue boats to be launched simultaneously within a specific timeframe. The chief officer was supervising the port side, and the coxswain therefore assumed the duties of officer in charge for rescue boat station No. 1.

Although BC Ferries’ At the Station Checklist specifies that the coxswain can assume the duties of officer in charge if no officer is present, in this occurrence the coxswain’s ability to supervise operations at rescue boat No. 1 was limited because he was engaged in an active role as coxswain. Moreover, while the coxswain was positioned on the rescue boat, his view inboard of the cradle post was obscured.

3.0 Findings

3.1 Findings as to causes and contributing factors

These are conditions, acts or safety deficiencies that were found to have caused or contributed to this occurrence.

- New rescue boats had been installed on the Spirit of Vancouver Island that were of a greater height than the original rescue boats.

- Some of the rescue boat crews had developed an informal practice of removing rescue boat No. 1’s brake release line bag from its on-board storage container and leaving it on the deck when the rescue boat was not self-launched.

- The chief officer experienced a high workload in which he had to attend to multiple tasks and was not available to supervise at rescue boat station No. 1.

- When the crew removed the brake release line bag from the rescue boat, no deck officer was present to take the bag from the crew; it was therefore left unattended on the deck.

- Although the coxswain assumed the responsibility of officer in charge of rescue boat station No. 1, his ability to supervise the launching operation was limited while he was actively engaged in his duties as coxswain.

- While slewing the rescue boat out, the brake release line became snagged in the rescue boat’s cradle post. The snag created tension on the brake release line that increased as the davit arm slewed further outboard, to the point that the davit brake released.

- Once the davit brake released, the rescue boat dropped suddenly, and the bottom inboard hull of the rescue boat hit the edge of the deck of the Spirit of Vancouver Island, causing the rescue boat to tip outboard.

- The coxswain and the bowman fell from the rescue boat into the water.

3.2 Findings as to risk

These are conditions, unsafe acts or safety deficiencies that were found not to be a factor in this occurrence but could have adverse consequences in future occurrences.

- If key components of a safety management system, such as risk assessments, reporting non-conformities, emergency drill planning, and valid checklists are not put into practice by companies and crews, there is a risk that the safety of passengers and crew will be compromised.

- If the duties of a chief officer during emergency drills require them to attend to multiple tasks under high workload, there is a risk that the emergency response will be inadequate.

3.3 Other findings

These items could enhance safety, resolve an issue of controversy, or provide a data point for future safety studies.

- Job aids provided to Spirit of Vancouver Island crew were not updated to reflect the specific differences between different types of davits and rescue boats on board.

4.0 Safety action

4.1 Safety action taken

4.1.1 British Columbia Ferry Services Inc.

Since the occurrence, British Columbia Ferry Services Inc. has taken the following safety actions:

- It has created and resourced a new Asset Management Services Office.

- It has updated all vessel-specific manual procedures, checklists, and quick reference guides related to rescue boat operations.

- It has completed its rescue boat policy with Fleet Operations Manual policy updates.

- It has checked crew proficiency. The standard practice is to record the date and the drill the employee participated in (such as person-overboard/Coxswain or Fire/Boat) and enter it into the employee’s Marine Emergency Duties book, initialled by the officer in charge of the drill.

- It has updated its risk management policy to include the requirement of a task analysis or risk assessment for introductions or modifications of safety-critical assets..

- It has created a Nautical Equipment Management Office to assist in the management and quality assurance of safety-critical assets by reviewing policy, procedures, and equipment as part of an ongoing Asset Management Improvement Strategy.

- It has added more focus on equipment readiness during audits.

- It has developed a controlled fall system for rescue boat crew.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s investigation into this occurrence. The Board authorized the release of this report on 13 November 2019. It was officially released on 27 December 2019.

Appendices

Appendix A – Area of the occurrence

Appendix B – General arrangement of Spirit of Vancouver Island at the time of the occurrence

Source: British Columbia Ferry Services Inc., with TSB annotations.

Appendix C – At the Station checklists for the Spirit of Vancouver Island and the Spirit of British Columbia

Source: British Columbia Ferry Services Inc., Spirit Class Specific Manual, 08.01.180A, Appendix A: Launch and Recovery of Rescue and Shepherd Boats Checklist, (25 July 2018).

Source: British Columbia Ferry Services Inc., Spirit of British Columbia manual, section 08.01.180A, Appendix A: Launch and Recovery of Rescue and Shepherd Boats Checklist (11 October 2018).

Appendix D – In the Boat checklists for the Spirit of Vancouver Island and the Spirit of British Columbia

Source: Spirit Class Specific Manual, 08.01.180A, Appendix A: Launch and Recovery of Rescue and Shepherd Boats Checklist (25 July 2018).

Source: Spirit Class Specific Manual, 08.01.180A, Appendix A: Launch and Recovery of Rescue and Shepherd Boats Checklist (11 October 2018).