Striking of a wharf

Roll-on/roll-off passenger ferry Apollo

Godbout, Quebec

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Vessel history

The Apollo (International Maritime Organization No. 7006314, Figure 1) is a Canada-flagged roll-on/roll-off passenger ferryFootnote 1 built in 1970 in Germany. Most of the Apollo's service was spent in northern Europe, sailing in the Baltic and North Seas. During its life, the vessel was owned and operated by different companies under several names before it was renamed Apollo in 1995. In 2001, the Apollo was acquired by Labrador Marine Inc., based in Newfoundland and Labrador. The vessel was operated for 18 years between Blanc-Sablon, Quebec, and St. Barbe, Newfoundland and Labrador, until it was sold to the Société des traversiers du Québec (STQ) in 2019. As an emergency measure to restore the marine connection between Matane, Baie-Comeau, and Godbout, Quebec, the STQ acquired the vessel as a replacement for the out-of-service roll-on/roll-off passenger ferry F.-A.-Gauthier.

At the time of the occurrence, the vessel was certified by the classification society Bureau Veritas, under the authority of Transport Canada, to carry 240 passengers and 30 crew members.

History of the occurrence

On 25 February 2019 at 0800,Footnote 2 the Apollo left the port of Matane for Godbout, Quebec, with 100 passengers and 28 crew members on board. The vessel's vehicle deck was fully loaded with cars and trucks. The voyage proceeded in a routine manner.

At approximately 1000, using the bridge telephone, the helmsman called the master in preparation for arrival. The master arrived in the wheelhouse at approximately 1008. The vessel was about 2 nautical miles (NM) from Godbout, making way at 15 knots while steering with the autopilot mode on. Taking into consideration a starboard beam northeast wind of 25 knots, the master decided to maintain speed to manoeuvre the vessel while maintaining a safe distance from the Godbout ferry wharf.Footnote 3 At 1012, the master ordered the helmsman to switch off the autopilot mode and steer manually.

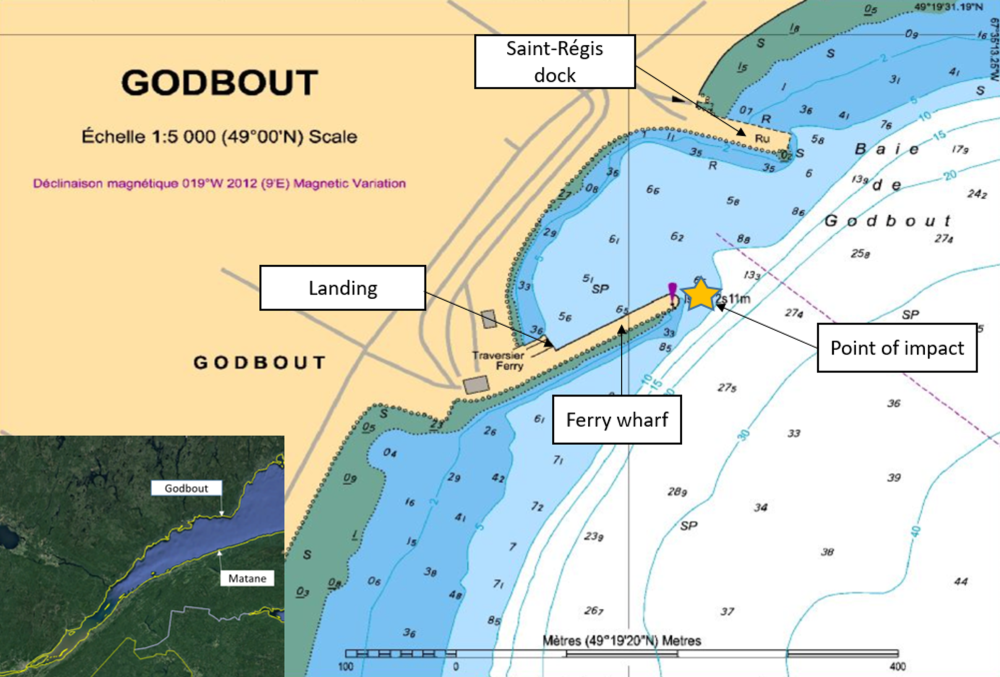

At about 1017, the vessel entered Godbout Bay. The master immediately slowed the vessel speed to 11.7 knots and ordered the helmsman to put the rudder to port and steer toward the Saint-Régis dock,Footnote 4 then toward the landing. The manoeuvre caused the vessel to turn toward the wharf faster than expected. While the vessel was turning rapidly, the master took the command of the vessel on the port navigation wing. He immediately turned the helm hard to starboard and again reduced the speed, keeping a forward minimum speed to maintain the ship's steering capabilities.

The vessel did not respond as expected due to water flow reduction on the rudders caused by the successive speed reductions. To compensate, the master reversed the starboard propulsion while keeping the port propulsion ahead and simultaneously activated the bow thruster. The vessel stopped turning to port but continued moving forward. When it became evident to the master that a collision with the end of the ferry wharf was unavoidable, to minimize the force of impact and subsequent damage, the master reversed the port engine so that both engines were working astern. The vessel continued to move forward slowly and deviated toward the ferry wharf because of the grey iceFootnote 5 that covered the harbour.

At 1018, the vessel made contact with the end of the ferry wharf (Figure 2). At 1019, following the impact, the crew briefly inspected the vessel to ascertain the extent of the damage. The inspection revealed a hole in the bow visor of about 1 m high by 2 m wide, with buckling over an area of about 9 m². At 1045, the vessel was secured at the ferry berth and the passengers disembarked. Despite the damage from the impact, the crew was able to open the visor and proceeded to unload the vehicle deck.

At around 1500, the Apollo was inspected by 2 Transport Canada marine safety inspectors. Following the inspection, the ship was allowed to proceed to Matane for repairs. At 1600, the Apollo departed Godbout without any passengers on board, escorted by the Canadian Coast Guard vessel Des Groseilliers. The Apollo arrived in Matane at 1930.

Environmental conditions

On 25 February, at the time of the occurrence, it was snowing and visibility was about 1 NM in Godbout, Quebec. The wind was from the northeast at 25 to 30 knots. The air temperature was approximately −6 °C. The ice coverage was 8/10.

Master's experience

The master of the Apollo joined the STQ fleet in 2015 as a second officer and as a relief chief officer. In November 2016, after obtaining a Master, Near Coastal certificate of competency, he began sailing as a relief master. He became a permanent master for the STQin March 2017. Since his employment, he had completed approximately 400 landings in Godbout, many of which in winter conditions, on other STQ vessels without any incident.

The master was part of the STQ team sent to Newfoundland and Labrador to take possession of the Apollo. The former owner's crew was in charge of the vessel transit from St. Barbe, Newfoundland and Labrador, to Matane, Québec. The master's familiarization with the vessel took place during this voyage. Additionally, as part of his training, sea trials were made outside of Matane and a landing exercise in Baie-Comeau and Godbout was performed to verify the compatibility of the vessel with the modifications that the STQ had recently made to its shore infrastructures.

Before the date of the occurrence, the master had completed 7 round trips from Matane to Baie-Comeau with the Apollo. On the day of the occurrence, the master was on his first voyage from Matane to Godbout with passengers on board.

Description of the vessel's propulsion and manoeuvring systems

Built in 1970, the Apollo was equipped with a conventional propulsion system consisting of two 4-stroke, single-acting diesel engines each rated to deliver 3330 kW, reduction gears, and 2 screw shafts each driving a variable-pitch propeller. The vessel was equipped with a fixed pitch electrical bidirectional bow thruster.

In 2005, the vessel's port engine was replaced by a main engine rated at 4000 kW. The response time of the new engine is faster than that of the starboard engine, which is older. The difference in response times must be taken into consideration when manoeuvring the vessel.

The vessel's steering is provided by 2 semi-balancedFootnote 6 rudders. Generally, all rudders experience decreased efficiency during low speed manoeuvring operations. This is caused by a decrease of water flow at the stern which affects the pressure acting on the rudders.

The Apollo's electrical power is supplied by 3 auxiliary engines generating 3-phase alternating current with a nominal power output of 500 kW each. The mechanical condition of the generators' diesel engines is such that they cannot operate at more than 50% of their load.

The 478 kW electrical transverse fixed-pitch bow thruster is designed to operate at 3 different speeds and provides the Apollo with transverse thrust during low speed manoeuvres. In spite of its design, the thruster can only be operated on its first speed for about 1 minute, and on its second speed for 15 seconds. The thruster's third speed is unusable given the limitations of the electrical supply. Prolonged use of the bow thruster causes the auxiliary engines to overheat, which in turn causes their overheat protection to automatically shut them down, creating a possible blackout situation on board. The inability to use the bow thruster to its full design capacity is an additional constraint on the master's ability to manoeuvre the vessel.

The vessel's navigation bridge consists of a wheelhouse that contains all the navigation instruments and controls, and of 2 open bridge wings. Each bridge wing is equipped with a console that has controls for the bow thruster, rudders, and engines. From the bridge wings, the navigation personnel have a full view of the wharf to aid in the docking manoeuvres.

Safety message

This investigation revealed the following conditions on board the Apollo:

- The 2 main engines had different power outputs and response times. The slower response of the starboard engine reduced the counteracting torque required during the approach manoeuvre.

- The inability of the auxiliary engines to operate at more than 50% of their nominal power rating prompted the master to minimize the use of the bow thruster while manoeuvring the vessel.

- The master's limited training and experience in manoeuvring the newly acquired vessel led to an incorrect assessment of the vessel's speed and course, and of the effects of ice and wind when approaching the Godbout ferry wharf.

For the safety of the vessel, its passengers, and the environment, it is important that all machinery designed to assist the master in manoeuvring the vessel be fully operational, and that the master be familiar with the machinery's responses and operational limitations.

About the investigation

This report is the result of an investigation into a class 4 occurrence. For more information, see the Policy on Occurrence Classification.

Terms of use

Non-commercial reproduction

Unless otherwise specified, you may reproduce this investigation report in whole or in part for non‑commercial purposes, and in any format, without charge or further permission, provided you do the following:

- Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced.

- Indicate the complete title of the materials reproduced and name the Transportation Safety Board of Canada as the author.

- Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of the version available at [URL where original document is available].

Commercial reproduction

Unless otherwise specified, you may not reproduce this investigation report, in whole or in part, for the purposes of commercial redistribution without prior written permission from the TSB.

Materials under the copyright of another party

Some of the content in this investigation report (notably images on which a source other than the TSB is named) is subject to the copyright of another party and is protected under the Copyright Act and international agreements. For information concerning copyright ownership and restrictions, please contact the TSB.

Citation

Transportation Safety Board of Canada, Marine Transportation Safety Investigation Report M19C0043 (released ).

Le présent rapport est également disponible en français.