Crew member injury

Self-propelled barge Rivière Saint-Augustin

Chevery, Quebec

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Description of the vessel

The Rivière Saint-Augustin (Figure 1) is a steel, self-propelled barge built in 2020 by Ocean Group at its shipyard in Isle-aux-Coudres, Quebec. The vessel is 23.73 m in length and of 109 GT. It is propelled by 2 diesel engines with a total capacity of 662 kW, driving fixed pitch propellers. It was commissioned and built to ferry cargo between Pointe à la Truite, Quebec, and Saint-Augustin, Quebec.

The vessel is owned and operated by the Société des traversiers du Québec (STQ), which is the authorized representativeFootnote 1 for the vessel. The vessel’s safe manning document allows operation with a periodically unattended machinery space. That is, the safe manning document allows operation without an engineering officer or small vessel machinery operator.

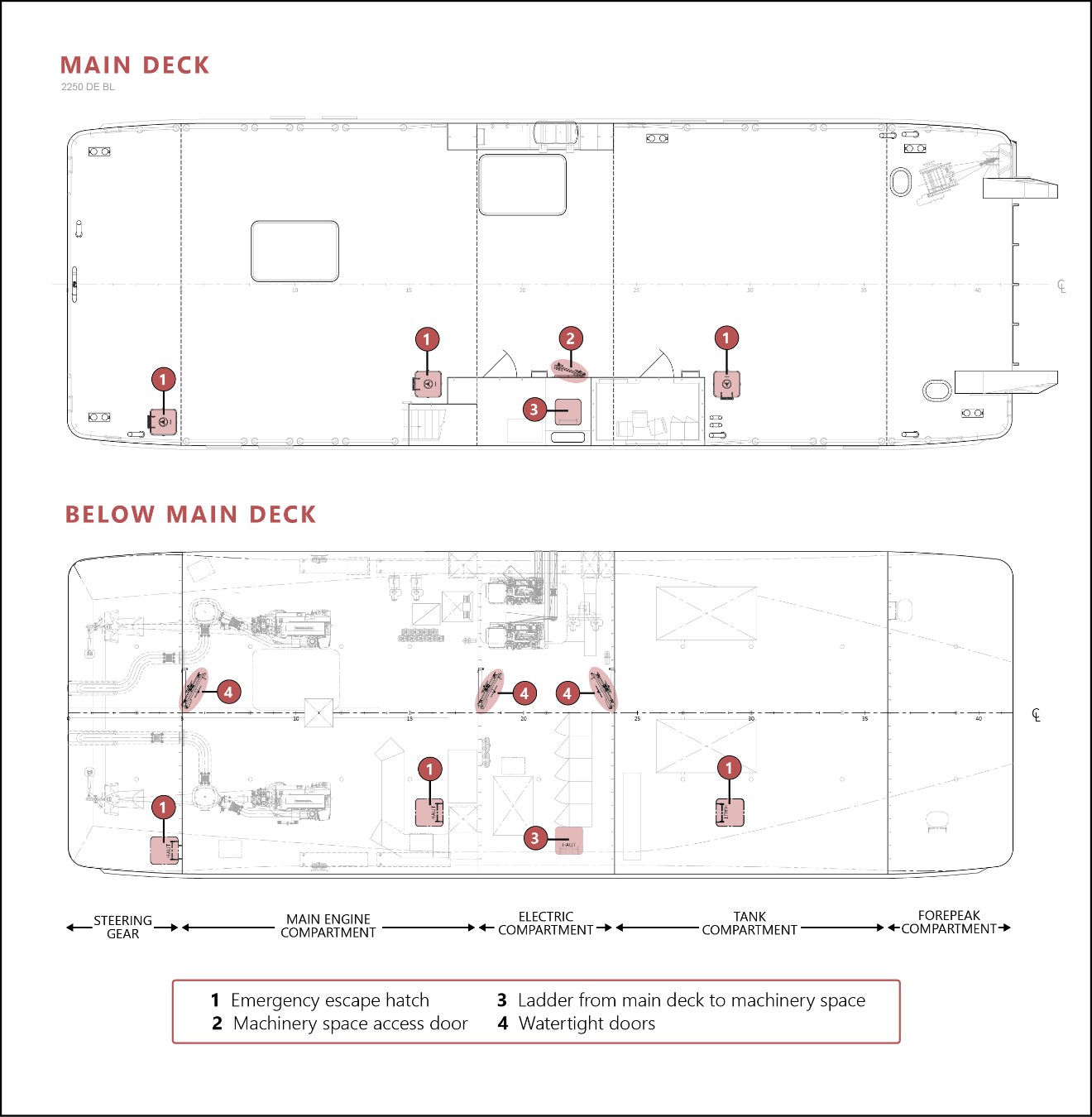

The vessel is subdivided into 5 watertight compartments under the main deck by transverse watertight bulkheads (Figure 2). Four of these compartments make up the machinery space: the steering gear compartment, the main engine compartment, the electrical compartment, and the tank compartment. Access to the machinery space compartments is through a watertight door, which is located on the main deck and hinged to open outward to the main deck. A vertical ladder leads to the electrical compartment. The 5th watertight compartment is the forepeak and is only accessible through flush watertight hatches on the main deck.

The 3 transverse bulkheads between the machinery space compartments are each equipped with a watertight door to allow access between compartments. Each of these compartments also has an emergency hatch leading to the main deck. To ensure vessel safety, crew must close all watertight doors and escape hatches on the main deck and in the machinery space when the vessel is at sea.

History of the occurrence

The vessel was expected to enter service in the fall of 2023, as soon as the dock in Saint-Augustin had been repaired and updated for a vessel of this size. The delivery voyage was being completed in stages: on 08 June 2022, the vessel sailed to Québec, Quebec, where it remained until 01 September. During this period, work on the vessel was being performed. A number of systems were creating false alarms and the vessel’s alarm and monitoring system was partially disabled by removal of the 2 fuses that supply electric power to the audible alarm indicators (sirens and buzzers), to avoid distracting the person at the helm of the vessel. On 01 September the vessel sailed to Chevery, Quebec, where it remained until 13 October.

In October, winterization work began and blanks were installed over the exhaust air outlets. The fire dampers in the ventilation system were also closed in an effort to retain heat in the machinery space, with the intention of using the exterior access door to supply air to the engine room. All crew members were aware that the blanks were installed. Only some crew members were aware that the fire dampers were closed.

On 13 October at 0858,Footnote 2 the vessel left the public dock at Chevery (Figure 3). The vessel was under the command of the chief officer, the master was on deck with the 2 deckhands, and the chief engineer was in the machinery space.

All 3 exterior doors, including the watertight access door to the machinery space, were left open and unsecured at the time of departure. The vessel proceeded at 3 knots down the channel that leads through the sandbar that lies across the entrance to the Nétagamiou River, with 1 engine running and clutched in.

At 0910, the master went to the wheelhouse. As a routine step, he ordered 1 of the deckhands to close and secure all 3 exterior doors, which resulted in the machinery space being sealed. At 0915 the vessel passed through the buoys marking the channel entrance. The chief officer clutched in the 2nd engine and increased speed to 10 knots and a corresponding engine operating speed of 1770 rpm.

At 0917, the master went to the general purpose crew space on the main deck, forward of the watertight access door to the machinery space. The chief officer remained in the wheelhouse navigating and steering the vessel.

At 0926, the master heard an unusual clapping noiseFootnote 3 originating from the starboard side natural air vent for the tank compartment.

At approximately 0927, the chief officer heard the engines starting to make a sound with a lower-than-normal frequency. He attempted to contact the chief engineer on the vessel’s internal communication system, but the chief engineer did not respond.

At 0928, the master went to investigate the source of the clapping noise. He attempted to enter the machinery space via the access door on the main deck but was unable to open the door. He then tried to access the tank compartment and main engine compartment via their respective escape hatches but was unable to open the hatches.

At 0930, the master opened the escape hatch to the steering gear compartment and then returned to the wheelhouse. He ordered the chief officer to enter the engine room via the steering gear compartment.

At 0931, the chief officer entered the steering gear compartment by its escape hatch. He opened the door between the steering gear compartment and the main engine compartment.Footnote 4 He saw the chief engineer through the watertight door between the engine compartment and electrical compartment, lying on his back on the deck with apparent head injuries. The door to the tank compartment was open. After assessing the situation, he entered the space to assist the chief engineer.

At 0932, the chief officer left the machinery space through the access door on the main deck to inform the master of the chief engineer’s injuries and to seek help in rescuing the chief engineer. The master called a nearby taxi-boat, the Eaux Scintillantes, for assistance and then turned the vessel to return to Chevery.

At 0944, the chief engineer, still unconscious, was extracted from the machinery space via the vertical ladder and the watertight access door. He was then evacuated to the Eaux Scintillantes, transferred to the local health clinic, and later transferred to a hospital in Québec.

Following the evacuation, the Rivière Saint-Augustin returned to Chevery and secured alongside at the public dock at 1000.

The chief engineer was treated in hospital for head injuries and released after a few weeks. The investigation was unable to determine what caused the injuries.

Personnel experience and certification

The master held a Master, 500 GT, Near Coastal certificate of competency. He had sailed as a licensed deck officer since 1986. He had been hired as an external consultant by the STQ and had been the Master of the vessel since June 2022.

The chief officer held a Master, Near Coastal certificate of competency. He had sailed as a licensed deck officer since 1989. He had been hired as an external consultant by the STQ to assist with the vessel’s sea trials in 2021.

The chief engineer held a Second Class Engineer, Motor Ship certificate of competency. He had sailed as a licensed engineer since 1984.

Ventilation and alarm and monitoring systems

Air is supplied through the ventilation system (Figure 4) to support the internal combustion of the main engines and ship service generators, to remove excess heat, and to prevent the accumulation of exhaust fumes and chemical vapours. Air is supplied to the main engine and electrical compartments by supply fans. At maximum continuous rating, the air consumption of the main engines is 25 m3/min each. Openings for air supply and exhaust are located on trunking above the main deck and on the side of the superstructure. The steering gear and tank compartments and the forepeak are ventilated through inverted vent pipes and natural circulation. Non-return valves are fitted on the vent pipes to prevent water ingress.

Fire dampers are installed in the air supply and exhaust ducts at the main deck level and can be closed to cut off the air supply in the main engine and electrical compartments. The fire dampers are operable from the main deck. When the vessel is winterized, specially designed blanks are installed on the outboard-facing exhaust outlets to keep the space warm and prevent water ingress.

The vessel is equipped with an alarm and monitoring system (AMS). Operator stations for the AMS are located in the main engine room and on the navigation deck. When machinery operates outside of pre-defined operating parameters, an alarm condition is created. For example, alarms will sound when watertight doors are left open or when the air flow drops below a set rate. Audible alarm indicators sound on the main deck and in each machinery compartment. As well, visual indicators appear on both operator stations.

In this occurrence, when the watertight access door was closed, air supply to the main engine compartment was cut off. When the chief officer increased the vessel speed and brought the engines to full load, the air demand required to sustain main engine internal combustion increased. A pressure differential between the machinery space and the outside resulted, causing the exterior door and emergency escape hatches to become stuck closed.

The audible alarm indicators were disabled, and the master and crew were alerted to the situation only by the clapping sound coming from the non-return valve on the vent pipe of the starboard tank compartment and by the change in engine sound.

The decision to close the main engine and electric compartment fire dampers was not communicated amongst the crew. Decisions to remove the AMS audible alarm indicator fuses and to begin winterization work before arrival in Saint-Augustin were not communicated to shore management nor documented in the vessel’s log or maintenance records.

Risk management

Vessel operators must be cognizant of the hazards involved in their operations and proactively manage them to reduce risks to as low as reasonably practicable. Implementing effective risk management processes provides vessel operators with the means to identify hazards, assess risks, and establish ways to mitigate them. A documented and systematic approach also helps ensure that individuals at all levels of the operation have the knowledge, tools, and information necessary to make effective decisions in any operating condition.

In this occurrence, the master, chief officer, and chief engineer were hired as external consultants and were expected to prepare the vessel for entry into service and deliver it to Saint-Augustin. Their main tasks included the preparation of the vessel for inspection and certification by Transport Canada, and the development of the written procedures for the vessel.

At the time of the occurrence, initial risk assessments required for new vessels by the STQ’s safety management system (SMS) had been postponed until an undetermined date in 2023. The master and chief engineer had not received any training on, or familiarization with, the STQ’s SMS or risk assessment processes. The chief engineer had not received any formal training on the vessel’s propulsion machinery, auxiliary systems, or the AMS. The chief engineer was preparing procedures to operate the vessel's machinery with a periodically unattended machinery space for the future crew at Saint-Augustin.

TSB Watchlist

The Watchlist identifies the key safety issues that need to be addressed to make Canada’s transportation system even safer. Safety management is one of these issues. In the marine sector, TSB investigations have found that, even when formal processes are present, they are often not effective in identifying hazards or reducing the risks.

Safety messages

Where changes are planned to vessel operating systems or parameters, it is essential that the crew communicate these plans among each other and with shore management, especially where the changes could compromise crew or vessel safety.

When new vessels are acquired, risk assessments must be completed before the vessels are operated, to improve safety.

Authorized representatives must ensure that vessel crew members—no matter the level of experience or duration of employment—are fully aware of their responsibilities in managing safety and the resources available to them.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s investigation into this occurrence. The Board authorized the release of this report on . It was officially released on .