Risk of collision and capsize

General cargo vessel Saga Beija-Flor and pleasure craft BC4010135

Vancouver Harbour, British Columbia

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

On 15 October 2022, the general cargo vessel Saga Beija-Flor and the pleasure craft BC4010135 came in close proximity and were at risk of collision in Vancouver Harbour, British Columbia. The pleasure craft was overturned, and its occupants entered the water. The occupants were subsequently recovered by vessels in the area and were transported to a local hospital.

1.0 Factual information

1.1 Particulars of the vessels

Name / vessel number | Saga Beija-Flor | BC4010135 |

|---|---|---|

International Maritime Organization (IMO) number | 9160798 | N/A |

Official number | HK - 0373 | BC4010135 |

Port of registry | Hong Kong | N/A |

Flag | Hong Kong | Canada |

Type | General cargo vessel | Pleasure craft |

Gross tonnage | 29 729 | N/A |

Length | 199.20 m | 5.49 m |

Breadth | 30.50 m | N/A |

Cargo | Steel (7705 tonnes) | N/A |

Design draft | 11.823 m | N/A |

Draft at the time of the occurrence | Forward 5.5 m, aft 7.6 m | N/A |

Crew | 22 crew | 3 occupants |

Built | 1997 | 2013 |

Propulsion | 1 diesel engine of 12710 hp | 115 hp outboard engine |

Owner | Saga Shipholding (Norway) AS | Vancouver Boat Rentals Ltd. |

Manager | Anglo-Eastern Ship Management | Granville Island Boat Rentals |

Classification society / recognized organization | DNV | N/A |

1.2 Description of the vessels

1.2.1 Saga Beija-Flor

The Saga Beija-Flor (Figure 1) is a general cargo vessel built by Oshima Shipbuilding Co. Ltd. in Japan. It is designed to carry general cargo in bulk as well as containers, grain, and heavy cargoes. The vessel has 10 cargo holds and two 40-tonne gantry cranes. The cranes are stowed aft in front of the accommodation spaces.The forward edge of the gantry crane is 47 m forward of the accommodation spaces in its stowed position. The engine room and accommodation spaces are located aft.

The bridge is equipped with all of the required navigational equipment, including a navigation console that contains the conning station, propulsion controls, 3 cm and 10 cm radars, and an ECDIS (electronic chart display and information system). The vessel is equipped with a differential global positioning system, an automatic identification system, and a voyage data recorder.

1.2.2 Pleasure craft BC4010135

BC4010135 (Figure 2) was a Glastron 18 (2013 model) pleasure craft, constructed of fibreglass with a 115 hp outboard engine that was installed in 2022. It consisted of a single deck with the control station on the starboard side. The vessel was equipped with an engine cut-off switch, a global positioning system (GPS) tracker, 2 fenders, 2 paddles, a spare fuel tank, and a safety kit that consisted of a rope, flashlight, whistle, and fire extinguisher.

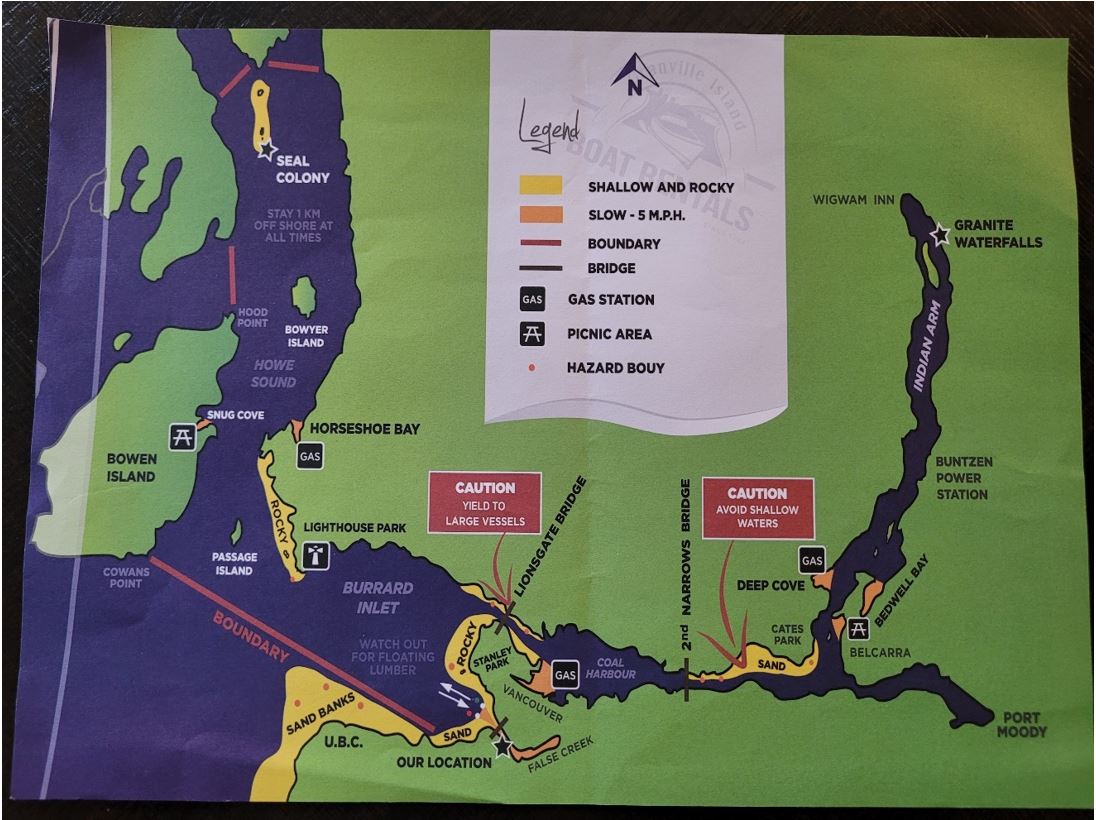

The vessel was owned by Vancouver Boat Rentals Ltd. and was used for hourly rentals operating out of Granville Island, British Columbia (BC). A list of boating tips and a map of areas of interest (seal colony, granite waterfalls, Deep Cove) was displayed on board. The map (Appendix A) also indicated basic features of the operating area, such as boundaries to navigation of shallow and rocky areas, speed restrictions, and bridges. The rental company’s emergency phone number was posted near the steering console. Renters were provided with personal flotation devices (PFDs) before boarding.

1.3 History of the voyage

1.3.1 Saga Beija-Flor

On 15 October 2022, the Saga Beija-Flor was docked at Berth 9 at Fraser Surrey Docks, BC. There, in preparation for departure, the crew tested the vessel’s engines, steering, and other equipment; no deficiencies were noted. At 0648,All times are Pacific Daylight Time (Coordinated Universal Time minus 7 hours). the Saga Beija-Flor departed the docks for Lynnterm Terminal in Vancouver HarbourThe voyage plan was completed by the vessel crew prior departure. after completing the master–pilot exchange. The bridge team comprised a pilot from Fraser River Pilots (the Fraser River pilot), the master, the third officer as the officer of the watch (OOW), and the helmsman. A pilot from British Columbia Coast Pilots (the BC Coast pilot) was also on board; the Fraser River pilot formally handed the vessel over to the BC Coast pilot and disembarked at approximately 0900.

At approximately 1025, as the vessel approached the Lions Gate Bridge,The Lions Gate Bridge is a suspension bridge that crosses the First Narrows of Burrard Inlet and connects the City of Vancouver, British Columbia, to the North Shore municipalities of the District of North Vancouver, the City of North Vancouver, and West Vancouver. per common practice, crew members walked the starboard anchor back to approximately 1 m above the water and were on standby for emergencies. Crew members were also at the forward and aft stations preparing mooring ropes. The vessel passed under the bridge at approximately 1035 at a speedSpeed of the vessel is expressed as Speed Over the Ground (SOG). of about 10.2 knots. The pilot and OOW individually observed a pleasure craftThis was a larger pleasure craft (approx. 40 to 50 feet in length) and different from the pleasure craft involved in the occurrence. off the starboard bow proceeding eastbound in the same direction as the Saga Beija-Flor. Once clear of the bridge, the pilot ordered a few small alterations to port.

At approximately 1048, when the Saga Beija-Flor had passed Brockton Point, the second officer was preparing mooring lines on the poop deck when he was alerted by the chief engineer, who was conducting rounds at the time, of people in the water. They observed a capsized pleasure craft and 3 people in the water approximately 3 m from the vessel’s port side and reported the incident to the master. The master relayed the information to the pilot. The pilot went to the vessel’s bridge wing to verify the report of the incident and observed the capsized pleasure craft almost dead astern in the Saga Beija-Flor’s wake. Upon returning to the vessel bridge, the pilot heard over very high frequency (VHF) radio that a nearby tug had reported the incident to Marine Communications and Traffic Services. The pilot instructed the crew to reduce vessel speed (half ahead to slow ahead on the telegraph) and put the rudder to port.

The pilot observed a tug responding to the incident and the vessel continued its voyage to the Lynnterm Terminal. The tugs for berthing were made fast alongside the Saga Beija-Flor at 1100, and the vessel was all fast at the terminal by 1330 (see Figure 3 for vessel track and occurrence location).

At the time of the occurrence, the OOW was primarily manning the telegraph and carrying out the engine orders given by the pilot. The master was at the ECDIS console, the pilot was conning the vessel from inside the vessel bridge and monitoring the portable pilot unit, and the helmsman was steering the vessel. Before the chief engineer observed it, capsized, the pleasure craft had not been acquired or tracked by the bridge team using the automatic radar plotting aid on the 3 cm radar.The investigation could not determine the status of the 10 cm radar because this information was not captured by the vessel’s voyage data recorder.

1.3.2 Pleasure craft BC4010135

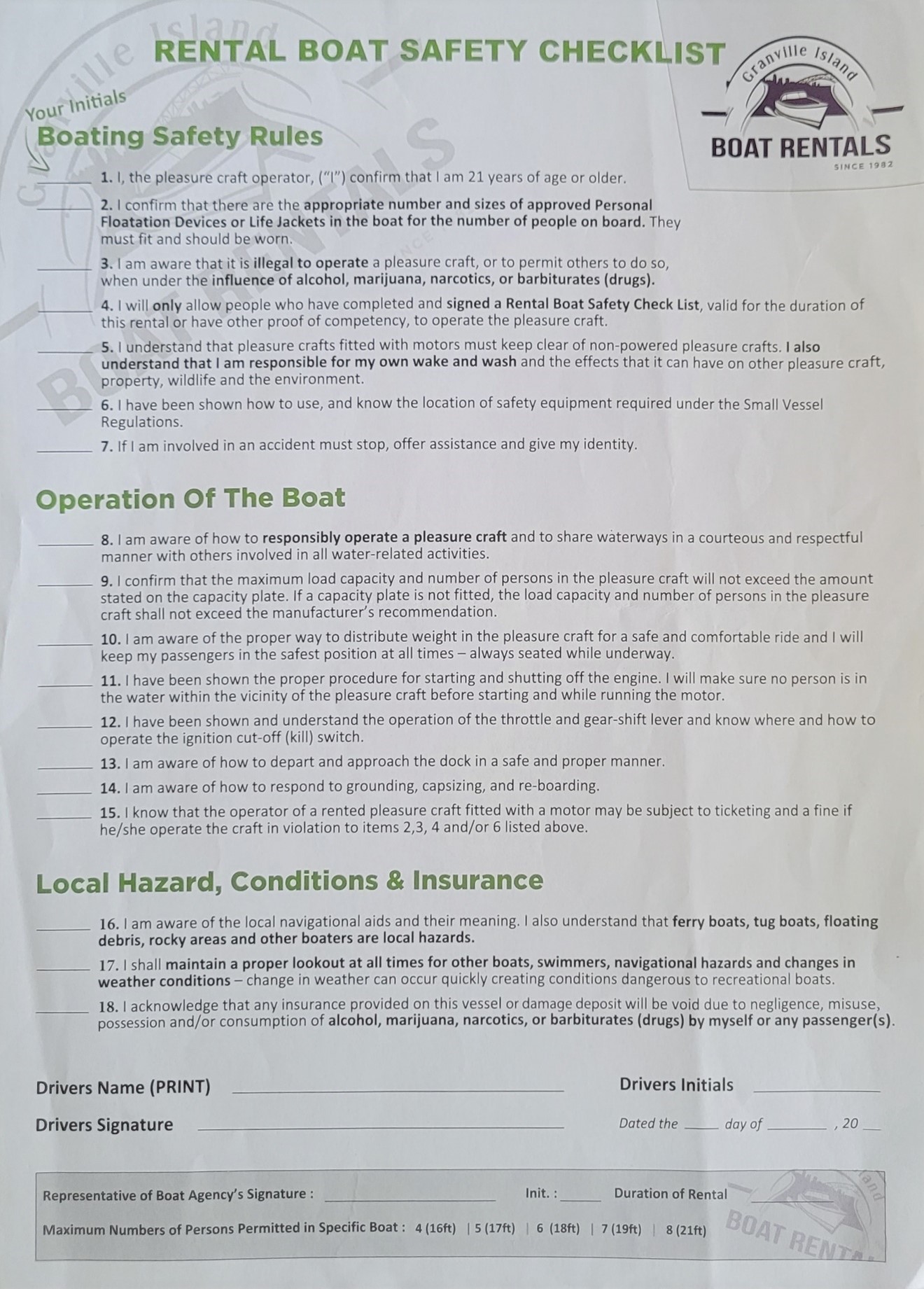

On 15 October 2022, pleasure craft BC4010135 was scheduled to be rented for 4 hours, from 0930 to 1330. At approximately 0855, 3 people arrived at the office of Granville Island Boat Rentals, on Granville Island in Vancouver, BC, and were shown a training video. In response to a comment from them that the video contained useful information and it would be advantageous for inexperienced boaters to receive such information earlier, office staff assured the group that many other people had rented pleasure craft for the first time from the company, and that GPS tracking allowed staff in the office to monitor the pleasure craft’s position at all times. Additionally, the pleasure craft would sound an alarm if it were navigated to a location where it was not supposed to be. The 3 people then completed and signed the Rental Boat Safety Checklist (Appendix B) and signed the Release and Indemnity Agreement.The agreement includes details of the occupants, operator responsibilities, as well as conditions of use and acknowledgement of the same. A staff member from Granville Island Boat Rentals also signed the Rental Boat Safety Checklist and Release and Indemnity Agreement. The 3 people donned PFDs and were provided with a demonstration of the pleasure craft’s controls and the engine cut-off switch. The entire process, from arrival to boarding, took approximately 30 minutes.

The 3 people boarded BC4010135 with 2 dogs and departed from Granville Island at approximately 0939 for a trip to Deep Cove. One occupant acted as the operator and was at the wheel while 1 occupant sat on the adjacent seat holding 1 dog, and the other sat behind with the 2nd dog. At approximately 0948, the pleasure craft strayed into an area deemed shallow and rocky by the rental company, which triggered an audible alarm. In response, the operator slowed the pleasure craft and changed direction into deeper water.

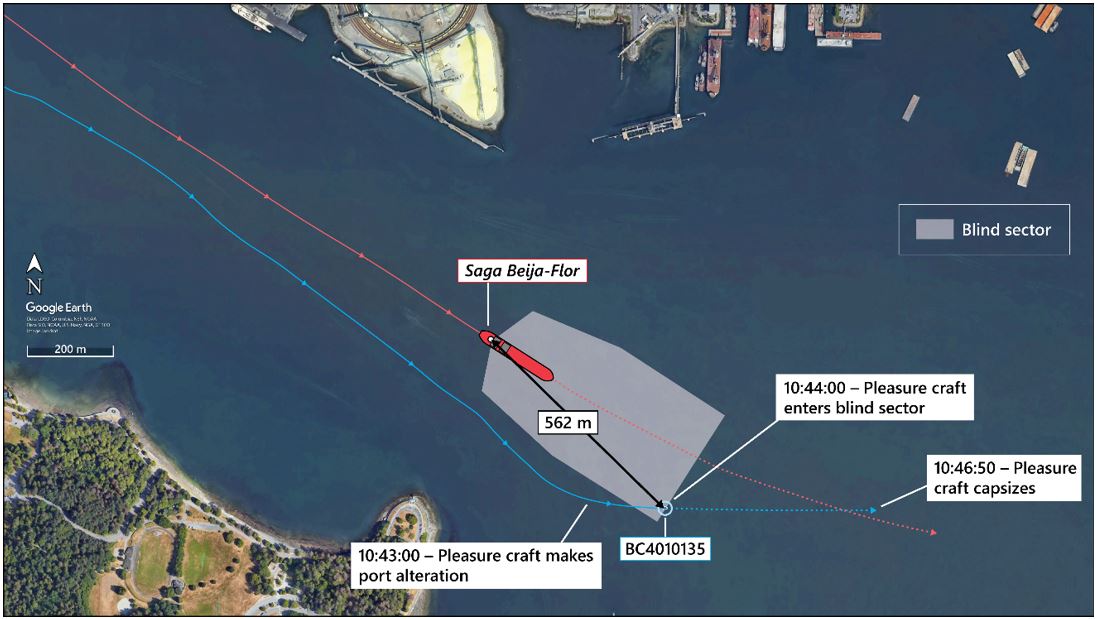

At approximately 1031, the pleasure craft passed under the Lions Gate Bridge at a speed of 5.9 knots, keeping to the centre of the channel. At about 1043, the operator made a course alteration of approximately 30° to port, heading toward the centre of the Second Narrows. At approximately 1046:50, the pleasure craft crossed the bow of the Saga Beija-Flor at close proximity.

The operator of the pleasure craft suddenly heard the 2 other occupants call out and looked around to see the bow of the Saga Beija-Flor right above him. Shortly thereafter, the pleasure craft capsized, and all occupants entered the water (see Figure 3 for occurrence location). The Saga Beija-Flor continued its course and passed approximately 3 m to the right of the capsized pleasure craft and its occupants. Two occupants stayed afloat in the water in the vicinity of the capsized pleasure craft, while the operator clung onto the outboard engine.Once capsized, the engine was automatically disabled by the engine cut-off switch. The 2 dogs were not found.

At 1049, the tugs Saam Venta and SST Salish observed the overturned pleasure craft and 3 people in the water. The master of the Saam Venta notified Marine Communications and Traffic Services in Victoria, BC, and both tugs proceeded to the occurrence site. Once the Saam Venta was alongside the pleasure craft, 1 person was able to transfer onto the tug with assistance from tug crew.

The Saam Venta was able to recover another person from the water using a Jason’s CradleA Jason’s Cradle is a piece of maritime lifesaving equipment that is designed to retrieve people quickly and horizontally from the water. as a ladder. A deckhand from the SST Salish boarded the Saam Venta to assist.

At approximately 1058, the harbour patrol boat VFPA 5 arrived on scene and was able to recover the remaining person from the water using a ladder. At 1110, the other 2 people were transferred from the Saam Venta to the harbour patrol vessel, which then transported all 3 people to shore. They were then taken to the hospital by ambulance.

1.4 Environmental conditions

At the time of the occurrence, the wind was light from the northwest. The swell height was 0.1 m with a 2-knot flood at First Narrows. Skies and visibility were clear. The air temperature was 13 °C, and the water temperature was 12 °C.

1.5 Granville Island Boat Rentals operation

The company rents out pleasure craft on an hourly basis between May and October. The boats are between 4.86 m (16 ft) and 6.38 m (21 ft) in length and can carry from 4 to 8 occupants.

Renters are required to arrive approximately 30 minutes before their scheduled departure. During this half-hour period, they watch a training video, undergo on-dock familiarization with the pleasure craft they are renting, and complete the company’s Release and Indemnity Agreement (conditions of use) as well as its Rental Boat Safety Checklist. The training video runs for 6 minutes and 30 seconds and contains important information pertaining to pleasure craft operation, route information, navigation instructions, and safety information. All renters are provided with PFDs before departing the dock.

The operating area for rented pleasure craft is between Bowen Island and Indian Arm and is indicated on the on-board map (Appendix A). Maximum speed limits were also provided.Speed limits were indicated in the training video, on the release and indemnity agreement, and on the on-board map. Pleasure craft operators are instructed to keep 1 km offshore, where possible. Consumption of alcohol is not permitted, and all occupants are required to embark and disembark from the boat rental office. Each pleasure craft is fitted with a GPS tracking device that allows the company to track the pleasure craft’s position and speed. When the pleasure craft goes outside a predetermined area or travels at a high speed, an alarm sounds, which provides a warning to the operator. The training video warns operators that any GPS-tracked reckless driving will result in a forfeit of the rental deposit.

No previous boating experience or a Pleasure Craft Operator Card (PCOC) is needed to rent and use the company’s pleasure craft that are less than 5.8 m (19 ft) in length, and the company’s marketing materials assure customers with no previous boating experience that operating the pleasure craft is safe and easy.According to the Granville Island Boat Rentals’ website, “[e]ven if you have never driven a boat before there is no need to worry, our easy to operate boats make boating fun for everyone. Driving is easy with a lever to control your speed and a wheel just like a car to steer. Granville Island Boat Rentals staff make sure everyone is comfortable before they leave the dock and go through everything you need to know like maps of the area, how to drive the boat and safety equipment. Navigating the waters around Vancouver is easy as there are many landmarks to help guide you.” (Source: Granville Island Boat Rentals, “Boat rentals in Vancouver,” at https://boatrentalsvancouver.com [last accessed 23 July 2024]). The company provides a complimentary 1-day boating licence to operators before departure. Clients operating pleasure craft that are longer than 5.8 m are required by company policy to have a PCOC.

The operator involved in this occurrence had no previous boating experience and was not informed of the training video before arriving at the company’s office. The company did not evaluate the operator’s understanding of the instructions contained in the training video.

1.5.1 Competency to operate a pleasure craft in Canada

The Competency of Operators of Pleasure Craft Regulations indicate that all operators of pleasure craft fitted with a motor that is used for recreational purposes are required to have proof of competency. Proof of competency is not required in the following situations: • The boat is being operated in the waters of Nunavut or the Northwest Territories. • A visitor to Canada is operating the boat he or she brought into Canada for less than 45 consecutive days.

- PCOC

- Certificate from a Canadian boating safety course completed before 01 April 1999

- Professional marine certificate or equivalent from Transport Canada’s (TC) List of Certificates of Competency, Training Certificates and Other Equivalencies accepted as Proof of Competency when Operating a Pleasure CraftTransport Canada, List of Certificates of Competency, Training Certificates and Other Equivalencies accepted as Proof of Competency when Operating a Pleasure Craft, at https://tc.canada.ca/en/marine-transportation/marine-safety/list-certificates-competency-training-certificates-other-equivalencies-accepted-proof-competency-when-operating-pleasure-craft (last accessed 07 August 2024).

- Completed rental boat safety checklist, which is valid only for the rental period

- For a visitor to Canada, an operator card or other document that meets the requirements of his or her home state or countryTransport Canada, SOR/99-53, Competency of Operators of Pleasure Craft Regulations (as amended 06 October 2020), section 4.

1.5.2 Pleasure Craft Operator Card

To obtain a PCOC, candidates must pass a boating safety test; TC recommends taking a boating safety course as the best way to prepare for the test. All boating safety courses and tests leading to the issuance of a PCOC are delivered by course providers accredited by TC. Courses are available in classroom, self-study, and online formats.

Topics covered in a boating safety course include

- the responsibilities of a boat operator;

- the minimum safety equipment required on board a boat;

- how to prevent unsafe situations once underway;

- how to share waterways with others, including larger and less manoeuvrable commercial vessels;

- a review of regulations that relate to pleasure boating; and,

- how to respond in an emergency.

The test consists of 50 multiple choice questions and has a passing mark of 75%. Once obtained, a PCOC does not expire.

1.5.3 Rental Boat Safety Checklist

If operators renting a pleasure craft from a rental agency do not already have proof of competency, they may complete a rental boat safety checklist to meet the requirement.

The rental agency will use the safety checklist as the basis for providing operators with information pertaining to the operation of the pleasure craft, fundamental boating safety rules, and the geographic features and hazards in the area in which the pleasure craft will be operated. Both parties (the rental agency and the pleasure craft operator) must sign the checklist, and the operator must carry it on board. This serves as proof of competency for the rental period only. There is no requirement to complete a boating safety test.

TC has a rental boat safety campaignTransport Canada, “Rental boat safety,” at https://tc.canada.ca/en/campaigns/rental-boat-safety (last accessed 23 July 2024). for businesses that rent pleasure craft to the public. The guidance includes best practices for making safety a part of every aspect of the rental experience. Businesses are advised that customers should be able to visit the company website, meet with staff who are well trained in safety, and receive dockside safety briefings. It is recommended that staff have boating experience in nearby waters so they can share that information with customers.

TC provides rental boat agencies with guidance in the form of safety posters and checklists for the various types of pleasure craft that rental boat agencies can use. In addition, TC’s Pacific Office of Boating Safety holds an annual rental boat information session to inform and educate all types of rental agents.

In January 2020, TC launched the Best Practice in Rental Boat Safety course. This optional online course educates rental boat agency staff of their responsibilities and obligations when renting boats to customers. The course takes about an hour to complete and is divided into 12 modules covering topics such as safety, client screenings, client briefings, local knowledge, and emergency communications. At the time of the occurrence, the staff at Granville Island Boat Rentals had attended the annual information session held by the Pacific Office of Boating Safety and completed this rental boat safety course.

1.5.4 Boating safety factors affecting novice boaters

For novice boaters, safely operating a pleasure craft requires an awareness of potential hazards and a mindset aimed at detecting cues in the environment. For people who are entirely unfamiliar with traffic in the local waters, pleasure craft handling, and best practices for avoiding obstacles, formal guidance is the first step. In this occurrence, formal guidance was provided primarily by the training video, which the operator had limited time to absorb and retain in his working memory.

Working memory is an important but limited intermediary between perception and learning. It links a person’s perception, attention, and long-term memory. When learners receive information visually, only the items they pay attention to enter their working memory. Generally, these items are processed into a mental model that moves the information from working memory into long-term storage, although not completely. “This loss of information may be more pronounced when a task must be performed immediately, and the presentation rate of instructions cannot be controlled by the user.”S. Dunham, E. Lee, and A. Persky, “The Psychology of Following Instructions and Its Implications,” American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education (August 2020), at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7473227/ (last accessed 23 July 2024).

In this occurrence, the 3 people renting the pleasure craft viewed the training video on safe boating practices that was provided by Granville Island Boat Rentals. They were unable to pause the video to ask for clarification on its content. To fulfill the rental agreement, they also completed the company’s Rental Boat Safety Checklist, thereby confirming acknowledgement of the rules and measures required to operate the rental pleasure craft. The checklist formed a type of operational guidance for the operator, based on individual responsibility.

The content of the checklist was focused on the operator acknowledging their responsibility for maintaining safe speeds and distances from obstacles and traffic while operating the rental pleasure craft, among other obligations. The stipulations contained in the checklist were directed only to the pleasure craft operator and did not refer to other occupants as being able to provide possible support in navigation or traffic awareness.

In a variety of transportation modes, situational awareness is a critical component of decision making. As a construct, situational awareness is defined as the perception of the elements in the environment within a volume of time and space, the comprehension of their meaning, and the projection of their status in the near future. The way in which a person builds situational awareness is key to safe navigation and can be divided into 3 stages: the perception of elements in the environment, the comprehension of their meaning, and the projection of their status in future.M. R. Endsley, “Toward a Theory of Situation Awareness in Dynamic Systems,” Human Factors Journal, Vol. 37, No. 1 (March 1995), pp. 32–64. To build accurate situational awareness in a marine setting, an operator must navigate in a way that allows them to perceive relevant cues within the vessel and outside of it, understand what those cues mean, and accurately predict what that information means for the continued navigation. This includes watching for other vessel traffic 360° around the vessel. In this instance, the operator was unaware that the Saga Beija-Flor was approaching from behind.

If the first stage, perceiving essential elements in the environment, is not achieved, an operator may not be able to fully comprehend the navigation scenario, impacting their ability to predict hazards and plan appropriate action to avoid them. Environmental cues that occur from the operator’s communication with other occupants, their visual field, and aural warnings may supply immediate feedback that will prompt them to alter the pleasure craft’s speed, direction, and proximity to shore or other vessels.

1.6 Navigation in Vancouver Harbour and responsibilities of cargo vessels and pleasure craft

The Port of Vancouver is Canada’s largest port and the 3rd largest tonnage port in North America, with 27 major marine cargo terminals and connections to 3 railroads. The port is composed of different areas, including Burrard Inlet, English Bay, the Fraser River, and Roberts Bank. The area is also extremely popular with recreational boaters of all types and other water sport enthusiasts. This increases the likelihood of interactions between large commercial vessels and recreational craft, especially during the spring and summer months when recreational activity is at its peak.

In Canada, the Collision RegulationsTransport Canada, C.R.C., c.1416, Collision Regulations (as amended 07 June 2023). determine the responsibilities of vessels regarding passing, crossing, overtaking manoeuvres, and identify the stand-on and give-way vessel, which depends on the circumstances and the types of ships involved.

In crossing situations where a risk of collision exists, the vessel that has a vessel on its starboard side must keep out of the way and avoid crossing ahead of the other vessel.Ibid., Rule 15(a). Other than in circumstances of restricted visibility, a vessel overtakingOvertaking occurs when one vessel is coming upon another “from a direction more than 22.5° abaft [the vessel’s] beam.” (Source: Ibid., Rule 13(b).) another is required to keep out of the way of the vessel being overtaken.Ibid., Rule 13(a).

The regulations state: “Every vessel which is directed to keep out of the way of another vessel shall, so far as possible, take early and substantial action to keep well clear.”Ibid., Rule 16. The regulations also stipulate that if the vessel required to keep out of the way (the give-way vessel) is not taking appropriate action in compliance with the Collision Regulations, the vessel allowed to proceed (the stand-on vessel) may act to avoid collision by its manoeuvre alone.Ibid., Rule 17(a)(ii).

The Collision Regulations also require that a vessel of less than 20 m in length not impede “the passage of a vessel which can safely navigate only within a narrow channel or fairway.”Ibid., Rule 9(b). The Collision Regulations do not define “narrow channel,” nor does TC have an interpretation of First Narrows as a narrow channel under these regulations. TC notes, however, that based on the practices of mariners, First NarrowsFirst Narrows is defined as “those waters in Vancouver Harbour bounded to the east by a line drawn from Brockton Point to Burnaby Shoal, then 000° True north [, and] bounded to the west by a line drawn from Navy Jack Point to Ferguson Point.” (Source: Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Canadian Hydrographic Service, PAC 201, Canadian Sailing Directions: Juan de Fuca Strait and Strait of Georgia [July 2023], Chapter 5: Vancouver Harbour and Howe Sound, paragraph 62, section 3.1: First Narrows, subsection 3.1.1: Definition) (including the area in the vicinity of Burnaby Shoal) is considered a narrow channel.

1.6.1 First Narrows

According to the Canadian Hydrographic Service, “First Narrows forms the entrance to the west part of Vancouver Harbour. […] Navigating First Narrows is challenging, particularly for small craft. High traffic volumes and adverse sea conditions caused by wind, tide, and river outflow may be encountered. Mariners must exercise caution and keep a sharp lookout at all times [emphasis in original]”.Ibid., paragraphs 60–61.

The Port of Vancouver has established the First Narrows Traffic Control Zone (TCZ-1). According to the Port of Vancouver’s Port Information Guide:

The First Narrows Traffic Control Zone (TCZ-1) comprises an area enclosed:

- To the northwest by a line drawn from the north pier of the Lions Gate Bridge through Capilano Light, intersecting a line drawn due north from Ferguson Point at position 49°19ˈ22"N & 123°09ˈ32"W;

- To the southwest by a line drawn from Prospect Point, along the Stanley Park seawall, intersecting a line drawn due north from Ferguson Point at position 49°18ˈ40"N & 123°09ˈ32"W;

- To the east by a line drawn from Brockton Point off Stanley Park to Burnaby Shoal, then north to the eastern edge of Fibreco Dock.Port of Vancouver, Port Information Guide (February 2023), section 8.14, pp. 66–67.

The Port of Vancouver also developed procedures for the zone in consultation with the Pacific Pilotage Authority, BC Coast Pilots, and members of the broader marine industry. The purpose of the TCZ-1 procedures is to facilitate the safe navigation and efficient movement of vessels in this area of the port; details are published in the Port Information Guide, which is available online.

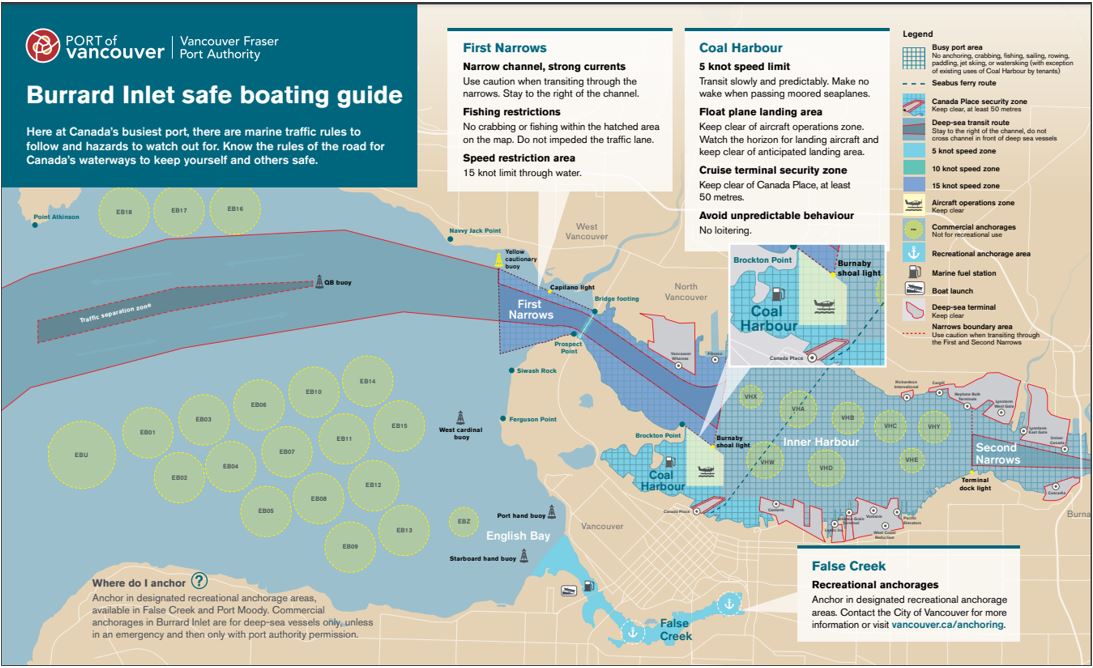

The Burrard Inlet safe boating guide, published by the Port of Vancouver, contains information for small vessel and pleasure craft operators. The guide identifies First Narrows as a narrow channel and a deep-sea transit route, advising pleasure craft to stay to the right of the channel and not to cross in front of deep-sea vessels. A map of Burrard Inlet from the guide is shown in Figure 4.

At the 2021 information session held by the Pacific Office of Boating Safety, the Vancouver Police Department Marine Unit raised concerns about the volume of traffic at the Lions Gate Bridge. Also at this session, the Port of Vancouver noted that it had conducted more than 1000 boating interactionsInteractions with recreational boaters are conducted by the Port of Vancouver to for the purpose of educating recreational users and raising awareness of safe boating practices. in 2020 and noted a lack of education among operators.

1.6.2 Guidance to recreational boaters

Numerous agencies have provided safety guidance to recreational boaters about avoiding collisions with larger vessels. This guidance is in the form of guides and information on safe boating practices.

1.6.2.1 Transport Canada’s Safe Boating Guide

TC’s Safe Boating GuideTransport Canada TP 511, Safe Boating Guide: Safety Tips and Requirements for Pleasure Craft (2019), p. 44, at https://tc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/migrated/tp_511e.pdf (last accessed 23 July 2024). provides recreational boaters with advice on how to avoid close-quarter situations. It informs boaters of the importance of keeping a constant watch and to stay clear of shipping lanes. It reminds boaters that it is hard for a large vessel to see recreational boaters or to change its course. A large vessel also takes longer to stop than a smaller pleasure craft.

The guide reminds boaters that the Collision Regulations apply in all navigable waterways and that vessels less than 20 m in length must not impede the passage of larger vessels within a narrow channel.

In this occurrence, neither the pleasure craft operator nor the other occupants kept a lookout astern, and none were aware of or alerted to the presence of the cargo vessel behind them.

1.6.2.2 Port of Vancouver

The Port of Vancouver’s website informs recreational boaters of the following boating practices:

Look

- Watch out for larger vessels: large, deep-sea vessels have limited visibility – don’t assume they can see you

- Never cross a tugboat and its tow: tow cables are often submerged and not visible

Listen

- Listen for aircraft: float planes landing and taking off need plenty of space

- Attend to signals from other vessels: five or more short blasts of a ship’s whistle means “danger – stay clear”. Monitor VHF 16 and 12

Act

- Be prepared to move out of the way: large, deep-sea vessels can’t move quickly, especially in narrow channels. Even if you have the right-of-way, you must yield to them

- Report incidents: contact [the] Port Operations Centre at 604-665-9086. In an emergency, and to report impaired boating, call 911Port of Vancouver, “Boating safety at the Port of Vancouver,” at https://www.portvancouver.com/marine-operations/marine-recreational-activities/ (last accessed 23 July 2024).

In addition, the Port of Vancouver publishes its Port Information Guide, which contains information concerning safe boating practices and procedures for recreational vessels operating in the Port of Vancouver.

1.6.2.3 Pacific Pilotage Authority

The Pacific Pilotage Authority has published a guide entitled Safe Boating in Deep Sea Shipping Navigation Areas to highlight some of the hazards to recreational craft when navigating in the vicinity of large vessels.

The guide advises the reader that

- large vessels do not have brakes and can take up to 2 nautical miles to come to a stop;

- it is difficult for a large vessel to get out of the way of a small boat;

- a small boat often does not appear on a large vessel’s radar and might be unseen by the vessel’s bridge team;

- a large vessel with an aft bridge could have a blind spot that extends several hundred metres ahead of the vessel and, when there is cargo on deck, this blind spot extends even further; and,

- to stay safe, pass no less than 500 m ahead of a large vessel and no less than 50 m on either side.Pacific Pilotage Authority, Safe Boating in Deep Sea Shipping Navigation Areas, pp. 2–3, at https://ppa.gc.ca/standard/pilotage/2019-07/PPA%20Safe%20Navigation%202019%20Web%20E.pdf (last accessed 23 July 2024).

1.6.2.4 Boating BC Association

The Shared Waterways campaign is a partnership between the Boating BC Association (Boating BC), the Vancouver Fraser Port Authority, and BC Ferries. According to the campaign website, “With more and more new recreational boaters getting on BC’s waterways, it is important for boaters to know the Rules of the Road and recognize that large vessels such as freighters, BC Ferries and Tug & Barges are difficult to maneuver [sic] and stop.”Boating BC Association, “Shared waterways,” at https://www.boatingbc.ca/cpages/shared-waterways (last accessed 23 July 2024). The website provides recreational boaters with safety tips on how to stay clear of these vessels.

1.7 Watchkeeping on board the Saga Beija-Flor

Vessels are required to be navigated safely in compliance with the Collision Regulations at all times. These regulations state “[e]very vessel shall at all times maintain a proper look-out by sight and hearing as well as by all available means appropriate in the prevailing circumstances and conditions so as to make a full appraisal of the situation and of the risk of collision.”Transport Canada, C.R.C., c.1416, Collision Regulations (as amended 07 June 2023), Rule 5. The composition of a vessel’s navigational watch must take this requirement into account to maintain a proper lookout.

According to the International Chamber of Shipping’s Bridge Procedures Guide, masters should take into account the following when determining the composition of the watch:International Chamber of Shipping, Bridge Procedures Guide, Sixth Edition (2022), Section 2.2.1, p. 27.

- Visibility, sea state, and weather conditions;

- Traffic density;

- Activities occurring in the area in which the ship is navigating;

- Navigation in or near traffic separation schemes […] or other routeing measures;

- Navigation in or near fixed and mobile installations;

- Proximity to navigational hazards;

- Ship operating requirements, activities, and anticipated manoeuvres;

[…]

- Operational status of bridge equipment, including alarm systems;

- Whether manual or automatic steering is anticipated;

- Any demands on the navigational watch that may arise as a result of exceptional circumstances; and

- Any other relevant standard, procedure, or guidelines relating to watchkeeping arrangements or the activities of the vessel

In addition to the above-mentioned guide, the Saga Beija-Flor’s managing company, Anglo-Eastern Ship Management, provided the master with guidance on bridge watch levels and assignment of duties for bridge team membersAnglo-Eastern Ship Management, Navigation and Mooring Manual (November 2018), Section 5.2. under different conditions that ranged from navigating in open waters to operating in confined areas with a pilot on board (tables 2 and 3).

Bridge watch levels | Conning Officer | 2nd Assisting Watch Officer | 3rd Assisting Watch Officer | Helmsperson**** | Lookout |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

B1* | OOW | N/A | N/A | On call | N/A |

B2 | OOW | N/A | N/A | On call | Lookout |

B3 | Master / Chief Officer | OOW | N/A | On call | Lookout |

B4** | Master / Chief Officer / Pilot | OOW | N/A | Helmsperson | Lookout |

B5*** | Master / Pilot | Master / Chief Officer / OOW1 | OOW2 | Helmsperson | Lookout |

Notes:

* B1 is permitted only during daylight hours; refer to Navigation and Mooring Manual chapter ‘Collision Avoidance’. Additional lookouts may be required depending on the circumstances of the case.

** In B4, Master / Chief Officer will man the bridge. However, in exceptional circumstances (such as long pilotages with minimal navigational hazards), Master may choose to have the OOW man the bridge along with the Pilot. Where Master or Chief Officer is available on bridge along with Pilot, OOW can take over duties of lookout.

*** In B5, if Conning Officer is Pilot, then 2nd Assisting Watch Officer should be Master or Chief Officer.

**** Helmsperson when not engaged in steering will perform Lookout duties.

Bridge watch level 4 and level 5 are “Red state of Alertness”. Refer to Navigation and Mooring Manual Chapter ‘Managing Distractions on Bridge’.

Duties | Bridge watch level B1 | Bridge watch level B2 | Bridge watch level B3 | Bridge watch | Bridge watch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Conn ship

| OOW | OOW | Master / Chief Officer | Master / Chief Officer / Pilot | Master / Pilot |

Traffic

| OOW | OOW | OOW | OOW | Master / Chief Officer / OOW |

Communications

| OOW | OOW | OOW | OOW | Master / Chief Officer / OOW |

Navigation

| OOW | OOW | OOW | OOW | OOW 2 |

Other duties

| OOW | OOW | OOW | OOW | OOW 2 |

Helm

| On call | On call | On call | Helmsperson | Helmsperson |

Lookout

| N/A | Lookout | Lookout | Lookout | Lookout |

* In Bridge watch level 4, the OOW can take over duties of lookout where Master or Chief Officer is available on bridge along with pilot.

At the time of the occurrence, the Saga Beija-Flor was operating at watch level B4. The bridge team consisted of the master, the third officer as the OOW, the helmsman, and the pilot. In accordance with company policy for watch level B4, the OOW took over the duties of the lookout leaving no dedicated lookout posted. His duties at the time included the following:

- Tracking traffic on radar and automatic radar planning aid

- Handling external VHF communications

- Handling communications with vessel traffic services and relevant authorities

- Monitoring, fixing, and verifying the vessel’s position

- Tending to the vessel’s telegraph

- Monitoring and reporting helm and engine response

- Maintaining logs and checklists

- Handling internal vessel communications

- Maintaining a lookout

1.7.1 Visibility from the bridge of the Saga Beija-Flor

According to the International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), vessels of not less than 55 m in length constructed on or after 01 July 1998 must meet certain requirementsInternational Maritime Organization, International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), 1974, as amended, Chapter V, Regulation 22. regarding the view of the sea surface from the vessel’s conning position, blind sectors caused by cargo, cargo gear, or other obstructions, and the horizontal field of view.

View of the sea surface from the vessel’s conning position should not be obscured by more than 2 ship lengthsFor the Saga Beija-Flor, 2 vessel lengths is 398.4 m. or 500 m (whichever is less) forward of the bow to 10° on either side of the vessel under all conditions of draught, trim, and deck cargo.

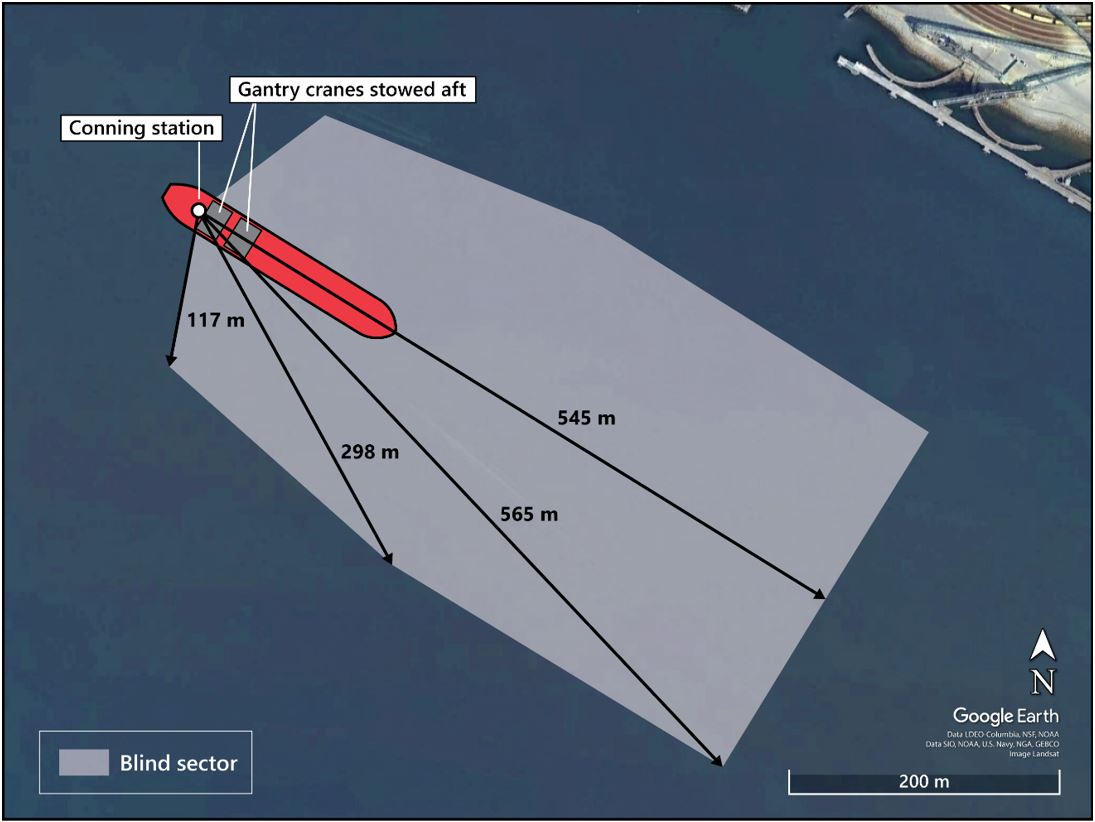

With the gantry cranes in the stowed position aft (Figure 5), the view of the sea surface from the Saga Beija-Flor’s conning position is obstructed (Figure 6).

The TSB used vessel plans to calculate the line of sight from the conning position to the sea surface at the operating drafts. On the day of the occurrence, the calculated line of sight from the conning position was approximately 545 m along the centreline, and approximately 565 m at an angle of 14.9°. The vessel complied with SOLAS with regard to navigation bridge visibility, but operated with a blind sector (Figure 7).

1.7.2 International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping for Seafarers: Lookout

The master of every vessel is required to ensure that watchkeeping arrangements are adequate for maintaining a safe navigational watch. Under the master’s direction, OOWs are responsible for navigating the ship safely during their periods of duty.International Maritime Organization, International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (STCW Code), Section A-VIII/2 Part 4: Watchkeeping at Sea. The International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification, and Watchkeeping for Seafarers (the STCW Code) indicates that

14 A proper lookout shall be maintained at all times in compliance with rule 5 of the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea, 1972, as amended and shall serve the purpose of:

.1 maintaining a continuous state of vigilance by sight and hearing, as well as by all other available means, with regard to any significant change in the operating environment;

.2 fully appraising the situation and the risk of collision, stranding and other dangers to navigation; and

.3 detecting ships or aircraft in distress, shipwrecked persons, wrecks, debris and other hazards to safe navigation.

15 The lookout must be able to give full attention to the keeping of a proper lookout and no other duties shall be undertaken or assigned which could interfere with that task.

16 The duties of the lookout and helmsperson are separate and the helmsperson shall not be considered to be the lookout while steering, except in small ships where an unobstructed, all‑round view is provided at the steering position and there is no impairment of night vision or other impediment to the keeping of a proper lookout. The [OOW] may be the sole lookout in daylight provided that […]

.1 the situation has been carefully assessed and it has been established without doubt that it is safe to do soInternational Maritime Organization, International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers, Section A-VIII/2 Part 4-1: Principles to be observed in keeping a navigational watch.

Despite the duties and obligations of pilots, the presence of pilots on board does not relieve the master or the OOW from their duties and obligations for the safety of the ship.

1.8 Cold-water immersion

Entering cold water, especially water below 15 °C, may trigger an initial cold-water shock response that causes the person in the water to gasp for air. Wearing an immersion suit, a PFD, or a lifejacket may prevent drowning during initial cold-water shock by keeping a person’s mouth away from the surface of the water, thereby preventing water ingestion or inhalation.

Cold-water shock is followed by cold incapacitation, which reduces a person’s ability to swim. Hypothermia can occur quickly, depending on water temperature; activities such as swimming or trying to board a raft increase heat loss and speed up the onset of hypothermia. This can lead to further incapacitation and death if the person is not rescued.

On the day of the occurrence, the occupants of the pleasure craft, who were wearing PFDs, were exposed to the effects of cold-water immersion once the pleasure craft capsized and they entered the 12 °C water.

1.9 Damage to vessels

No apparent damage was sustained by the cargo vessel Saga Beija-Flor.

The TSB conducted a post-occurrence examination of the pleasure craft after it was recovered and re-floated at Granville Island. The pleasure craft was observed to have sustained damage to its controls, electrical components, and steering. The front windshield was broken, and numerous seat cushions were scattered. All loose equipment was missing, likely as a result of the capsize. Numerous scrapes were observed on the topside of the vessel’s hull. The condition of the outboard engine and underside of the hull could not be assessed.

1.10 Personnel certification and experience

1.10.1 Saga Beija-Flor

The Saga Beija-Flor’s master and third officer held the required STCW qualifications for their positions on board.

The master obtained his certificate of competency as a master in 2015 and was promoted to master in 2020. This was his 3rd voyage as master. He completed bridge team management training in August 2022.

The third officer obtained his certificate of competency as an Officer in Charge of a Navigational Watch in 2018 and was promoted to third officer in 2022. This was his 1st voyage as third officer. He completed bridge team management training in September 2021.

The BC Coast pilot held a Pilot, Class I, Unrestricted licence at the time of the occurrence. He started his apprenticeship with British Columbia Coast Pilots in December 2018 and obtained his 1st pilot’s licence in September 2019.

1.10.2 Pleasure craft BC4010135

The occupants on board pleasure craft BC4010135 had no previous boating experience or knowledge of the Collision Regulations. They did not have any formal navigation training beyond completing the Rental Boat Safety Checklist before departure.

1.11 Distress alerting on board recreational vessels

The equipment that a recreational vessel is required to carry to communicate a distress signal depends on the vessel’s type and length. The required safety equipmentTransport Canada, TP 511, Safe Boating Guide: Safety Tips and Requirements for Pleasure Craft (2019). for a recreational vessel like BC4010135 to communicate distress is a watertight flashlight or 3 flares of type A, B, C, or D.Flares are not required for a boat that is operating on a river, canal, or lake in which it can never be more than 1 nautical mile (1.852 km) from shore or that has no sleeping quarters and is engaged in an official competition or in final preparation for an official competition.

At the time of the occurrence, BC4010135 carried a flashlight and whistle on board for emergency signalling.

1.11.1 Personal locator beacons

Personal locator beacons (PLBs) are portable units that can transmit a distress signal in much the same way as EPIRBs (emergency position–indicating radio beacons). PLBs are designed to be carried or worn by individuals and must be registered to provide vital personal information (name, address, emergency contact phone numbers, and medical conditions). PLBs are manually activated and operate on 406 MHz with a built-in low-power homing beacon that transmits on 121.5 MHz. PLBs also have an integrated GPS unit that gives them the capability to transmit specific location coordinates when a distress signal is sent. A PLB with a strobe light can further aid rescuers in their search.

Although PLBs can improve a person’s chances of survival in the event of an emergency, there are currently no regulations requiring occupants on board recreational craft to carry them. Some safety associations across Canada are promoting PLB use, especially in the fishing industry where crew members are at increased risk of falling overboard or experiencing a sudden capsizing.

In this occurrence, there was no means of communication other than the occupants’ personal cellphones, and the pleasure craft was not equipped with any automatic distress-alerting equipment.

1.12 Previous occurrences and survey

1.12.1 Similar occurrences

In addition to this occurrence, the TSB is aware of 137 similar occurrences that took place in Canada between 2018 and 2022, involving a risk of collision (121 occurrences) or a collision (16 occurrences). During 3 of the occurrences involving a collision, occupants of the pleasure craft entered the water.

1.12.2 Pleasure craft

The Canadian Marine Advisory Council’s Standing Committee on Recreational Boating met on 12 April 2023, at which time TC’s Office of Boating Safety released statistics concerning fatalities and collisions on board pleasure craft. For 2022, there were 83 fatalities and 80 collisions reported across Canada.

1.12.3 Canada-wide pilot survey

As part of its investigation into this occurrence, the TSB conducted a survey of licensed marine pilots across Canada. The survey was launched to collect additional data on the risk of collision between pleasure craft and commercial vessels under pilotage in Canada. The TSB received 76 complete responses during the 17 days the survey was accessible.

Among other questions, the survey asked pilots how often they have experienced close quarters or risk of collision with pleasure craft while piloting. Seventy-nine percent of respondents indicated they had experienced such situations occasionally or with some regularity, with 55% of all respondents indicating the latter.

Fifty-one percent of respondents indicated they never or only sometimes reported risk-of-collision situations that they encountered with recreational craft. Sixty-eight percent of respondents indicated they never or only sometimes experienced a lookout being posted at the bow on vessels where visibility from the bridge is obstructed by deck cargo or gear (such as cranes) while transiting confined waters.

The results of the survey indicate that

- risk-of-collision situations between commercial vessels and pleasure craft are widespread and generally underreported in Canadian waters; and,

- it is not a regular practice for commercial vessels to post a lookout forward while transiting confined waters, even when visibility from the bridge is obstructed by deck cargo or gear.

Additionally, better education and training for pleasure craft operators was identified by respondents as the most important factor to help reduce close-quarter situations and risk of collision with commercial vessels.

1.13 TSB laboratory reports

The TSB completed the following laboratory report in support of this investigation:

- LP072/2023 – Visual Blind Sector Analysis

2.0 Analysis

There was no indication that any equipment or machinery failure on the cargo vessel Saga Beija-Flor or pleasure craft BC4010135 contributed to this occurrence.

The analysis will focus on factors that prevented the crew of the cargo vessel and the occupants of the pleasure craft from seeing each other moments before the occurrence, watchkeeping on board vessels operating with a blind sector, training and familiarization for operators of rental boats, and distress-signalling equipment on small pleasure craft.

2.1 Movement of the vessels

As the pleasure craft was making its way toward Second Narrows, the operator’s primary focus was on keeping the pleasure craft 1 km from shore in accordance with the rental company’s direction. Additionally, he wanted to avoid receiving another alert from the global positioning system (GPS)-based alerting system like he had when he ventured close to shore earlier in the voyage. The operator therefore navigated towards the centre of the channel.

With no experience and having had relatively little time to absorb and commit the high-level content of the training video and rental checklist into his working memory, the novice operator likely reverted to what he perceived as the safest way of navigating the pleasure craft by moving into deeper waters away from the shoreline.

The manner in which the pleasure craft was navigated toward the Second Narrows bridge departed from marine navigation practices in a harbour setting by not establishing a 360° watch for other traffic. In the guidance material provided to operators, other occupants are not expressly described as possible support to the operator, and in this occurrence, the other occupants were not actively engaged in assisting the operator by maintaining a lookout for other traffic in the vicinity of the pleasure craft.

Additionally, the Port of Vancouver’s Burrard Inlet safe boating guide recommends staying to the right of the channel to avoid larger vessels, however this information was not made available to the operator.

In situations where novice operators are required to navigate in complex waterways like harbours, their skills and experience may be insufficient to effectively navigate, monitor traffic, and stay clear of obstacles. The reduction in performance for these tasks may be compounded if a novice operator is faced with navigating as an individual instead of as part of a team.

Because the operator was a novice boater and had little time to prepare for the voyage, he was unaware of the vessel traffic lanes in the area. His attention was on navigating toward the middle of the Second Narrows by making an alteration to port, so checking astern for surrounding traffic was not considered an essential task.

The visibility on the day of the occurrence was unaffected by obscuring phenomena such as precipitation, smoke, or fog. It is likely that clear visibility shaped the Saga Beija-Flor bridge team’s expectations of its ability to see and be seen by other traffic in the vicinity. In such conditions bridge teams may not use the radar to acquire and track every target.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

The bridge team on board the Saga Beija-Flor was not monitoring the pleasure craft either visually or by radar, and therefore did not detect the pleasure craft’s course alteration.

Additionally, visibility from the cargo vessel’s bridge was obstructed by the stowed gantry cranes. Using measurements from the vessel’s navigation bridge visibility plan, the TSB determined that the pleasure craft entered the Saga Beija-Flor’s blind sector at 1044:00, when it was 562 m forward of the bridge. Without a dedicated lookout from the bridge or at the bow, the crew had a narrow window of opportunity (approximately 1 minute) to recognize that the pleasure craft presented a hazard to navigation after it altered course to port (Figure 8).

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

Neither the pleasure craft operator nor the vessel’s master took action to avoid a close-quarter situation or risk of collision with the other vessel.

The pleasure craft operator’s reduced situational awareness, coupled with his focus on transiting the Second Narrows in the centre of the channel, contributed to the operator inadvertently crossing the Saga Beija-Flor’s track.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

The pleasure craft crossed the bow of the Saga Beija-Flor at very close proximity and capsized, likely under the influence of the cargo vessel’s bow wave, throwing all occupants into the water.

2.2 Pleasure craft operator training

The operator of the pleasure craft had no previous boating experience and relied on the cursory training and familiarization provided by Granville Island Boat Rentals to safely execute the voyage. Additionally, the operator felt reassured because the company promotes that no experience or boating licence is required to rent its boats and engage in recreational boating activities.

Although the rental process met regulatory requirements, there were a number of observations regarding the process that could contribute to a renter’s misperception of the risks of navigation in the area. The operator and other occupants of pleasure craft BC4010135 completed training and familiarization within 30 minutes before departure on the day of the rental, which is a very limited amount of time for someone with no previous experience to absorb and reinforce safety information.

The operator was not provided with an opportunity to review training material before the rental date. The training video is 6 minutes and 30 seconds long and provides no opportunity for viewers to stop or ask questions. It contains numerous important instructions regarding boat operation and navigation, and it is unrealistic for viewers unfamiliar with the area and with no marine experience to fully understand and remember those instructions within such a short time period. The training video indicates that customers may be asked some questions at the end of the video, but it is not company practice to evaluate understanding of the video; therefore, the operator’s understanding was not evaluated before departure. The company’s Rental Boat Safety Checklist advises operators to maintain a proper lookout at all times, but does not specify what a proper lookout entails or the importance of keeping a lookout all around. This approach gave the novice operator a short amount of time to understand the basics of boating safety but no means to reinforce any of the material with discussion or testing. None of the occupants were aware of the need to monitor vessel traffic behind the pleasure craft.

Briefing material for novice familiarization typically includes presentation of high-level information geared toward the existing skill level and knowledge of the person receiving instruction. For a person’s working memory to absorb new information, safety instruction should actively link the person’s perception (cognition and senses) with attentional focus (the means to create situational awareness) and connect those elements to the person’s long-term memory by creating a meaningful connection between the basic instructions and best practices in the local operating context, in this case, operating in Vancouver Harbour traffic.

In this occurrence, the operator was faced with a number of factors that required his attention in a short period of time: arriving at the marina for a set rental period, engaging in administrative paperwork, and attending the safety briefing and dockside familiarization. As a form of assurance, staff explained that an on-board GPS system would provide some oversight from the rental office while providing the operator with an alert if the pleasure craft was navigated outside a predetermined operating zone. The training video provided to the operator indicated that if reckless driving (such as high-speed turns, donuts, driving close to or in front of other boats) was recorded by the GPS, the operator’s deposit would not be refunded.

In new situations, people will invariably select and retain what they believe are the critical elements needed to achieve their goals. In this occurrence, it is likely that triggering the GPS alarm was a critical cue to the operator: knowing that he was being tracked by Granville Island Boat Rentals prompted him to alter course into the middle of the channel.

Current Transport Canada (TC) regulations require that operators of pleasure craft fitted with a motor be competent and hold the appropriate certificate or training, such as a Pleasure Craft Operator Card (PCOC). However, exceptions are made when it comes to pleasure craft rented from a rental agency. In such cases, the operator does not need a PCOC for the period of the rental as long as the operator and a representative of the agency complete a rental boat safety checklist. TC provides templates of this checklist on its website, and rental agencies are free to adapt them; these adapted checklists are not vetted by TC. Additionally, the operator completing the checklist is not required to be tested or evaluated on the information contained therein.

Being aware of the hazards at sea and the measures to mitigate the risks posed by these hazards can save a recreational boater’s life. In comparison with a rental boat safety checklist being completed moments before boarding a rental pleasure craft, completing a recognized course can significantly improve a recreational boater’s safety awareness and assist in identifying potential risks. While a rental boat safety checklist may be adequate for novice operators on a lake or similar waterway with limited vessel traffic and negligible hazards, that may not be the case for operating a pleasure craft in a busy and challenging waterway such as Vancouver Harbour. The operator in this occurrence did not have adequate training or experience to identify and mitigate the dangers and risks of navigating through a busy channel in Canada’s largest port. As a result, the pleasure craft was unintentionally manoeuvred through the centre of the channel without a lookout and was put directly in the path of the Saga Beija-Flor.

The Canada-wide survey of marine pilots conducted by the TSB indicated that risk of collision between commercial vessels under pilotage and pleasure craft is widespread across Canada. It also identified better education and training for pleasure craft operators as the most important factor to help reduce the risk.

Finding as to risk

Without adequate training and familiarization, operators with minimal or no previous experience may not be able to safely navigate a rental craft through busy channels and harbours, thereby putting the safety of occupants at risk.

2.3 Watchkeeping on board the Saga Beija-Flor

Regulations require that a vessel’s lookout be able to give full attention to the keeping of a proper lookout, and no other duties may be undertaken that could interfere with that task. The duties of the lookout and helmsman are distinct, and the helmsman should not be a lookout, except on small vessels where an unobstructed, all-round view is provided at the steering position and there is no impairment of night vision or other impediment.

Although the Saga Beija-Flor was adequately crewed by qualified and experienced personnel, no one was tasked with keeping a dedicated lookout. Maintaining a proper lookout is effective to avoid close quarter situations. In addition to his other officer of the watch duties, the third officer was tasked with keeping a lookout, which likely affected his ability to keep a lookout as the vessel transited through First Narrows. Neither the pilot nor the master who was also on the bridge at the time observed pleasure craft BC4010135crossing the bow, or as it passed the cargo vessel’s port side while capsized with its occupants in the water.

As the vessel transited through the harbour area frequented by recreational vessels, the gantry cranes in their stowed position obscured the horizontal field of vision up to a distance of approximately 565 m forward of the bridge. The interval between the pleasure craft making a port alteration and entering the cargo vessel’s blind sector would have provided a limited time frame (approximately 1 minute) for crew to identify the pleasure craft altering course before it became obscured by the vessel’s gantry cranes. Even when outside the defined blind sector and theoretically visible to the bridge team, the small pleasure craft would have been at the periphery of the gantry crane, likely highly inconspicuous and therefore easily overlooked while the bridge team was occupied with other navigational tasks.

The clear weather on the occurrence day was a factor in shaping the level of vigilance exercised by the bridge team on the Saga Beija-Flor. Clear visibility likely increased the bridge team’s expectations of the mutual visibility of vessels operating in the harbour and reduced the team’s perceived need to use the radar to acquire and track every target. In such conditions, bridge teams may not keep a continuous radar watch and, in this occurrence, the pleasure craft was not acquired and tracked using the vessel’s automatic radar plotting aid.

There were no effective defences implemented to adequately mitigate the hazards associated with the blind sector caused by the gantry cranes, such as posting a lookout at the bow.

If vessels with obstructed forward visibility do not have an effective lookout when transiting harbour areas, there is a risk that other vessels may go undetected, thereby increasing the risk of collision.

2.4 Distress alerting and survival

Once in the water, the occupants of the pleasure craft were exposed to the effects of cold-water immersion and risk of drowning. When a vessel rapidly capsizes, the survival of its occupants often depends on successfully transmitting a distress signal to search and rescue resources.

Distress signals are typically transmitted in 2 ways: manual activation, such as with very high frequency (VHF) digital selective calling (DSC) radios, flares, and personal locator beacons; or automatic activation when a vessel sinks, such as with emergency position–indicating radio beacons. Additionally, personal locator beacons can be worn by a vessel occupant and can therefore be activated even in person-overboard situations.

The only means of external communication on board pleasure craft BC4010135 was via the occupants’ personal cellphones. However, there are shortcomings with relying exclusively on a cellphone for marine communications, notably a potential lack of cellphone reception in the area of operation, accessibility during an emergency, and functionality of the equipment if exposed to sea water.

The Canadian Coast Guard cautions mariners that a cellphone is not a good substitute for a marine radio because the mobile radio safety system in the southern waters of Canada is based on VHF, radio/telephone, and DSC communications. A VHF call can be heard by the closest Marine Communications and Traffic Services centre and by vessels in the vicinity, so they could provide immediate assistance. Cellular networks, however, are a party-to-party system and do not have the benefit of a broadcast mode in an emergency situation.

In this occurrence, the pleasure craft was equipped with manually operated distress signals consisting of a flashlight and whistle. This severely affected the ability of the occupants to transmit a distress signal, particularly when they unexpectedly entered the water as the vessel suddenly capsized.

Without an effective means to transmit a distress signal after entering the water, occupants of recreational vessels will not be able to alert others that they are in danger, which puts their lives at risk.

Although the occupants of the pleasure craft were unable to transmit a distress signal and were exposed to the effects of cold-water immersion once the craft capsized, there were a number of factors that contributed to their survival:

- The tug Saam Venta was in the vicinity of the occurrence location and the tug master observed the overturned pleasure craft and people in the water.

- The tug immediately notified Marine Communications and Traffic Services and was at the scene in about 5 minutes to provide assistance.

- All occupants of the pleasure craft were wearing personal flotation devices (PFDs).

- The engine cut-off switch functioned as designed and disabled the engine when the operator entered the water.

3.0 Findings

3.1 Findings as to causes and contributing factors

These are conditions, acts, or safety deficiencies that were found to have caused or contributed to this occurrence.

- Without previous experience and with limited training, the operator of the pleasure craft was navigating a complex waterway unaware of the need to scan all around the vessel. Consequently, the operator and other occupants did not see the cargo vessel approaching from astern.

- The pleasure craft operator made a port alteration when approximately 575 m in front of the bow of the cargo vessel, putting the pleasure craft directly in its path.

- The bridge team on board the Saga Beija-Flor was not actively monitoring the pleasure craft either visually or by radar, and therefore did not detect the pleasure craft’s course alteration.

- The Saga Beija-Flor’s bridge team did not see the pleasure craft crossing the cargo vessel’s path because the craft was obscured by the vessel’s gantry cranes, which were in the stowed position.

- The pleasure craft crossed the bow of the Saga Beija-Flor at very close proximity and capsized, likely under the influence of the cargo vessel’s bow wave, throwing all occupants into the water.

3.2 Findings as to risk

These are conditions, unsafe acts or safety deficiencies that were found not to be a factor in this occurrence but could have adverse consequences in future occurrences.

- Without adequate training and familiarization, operators with minimal or no previous experience may not be able to safely navigate a rental craft through busy channels and harbours, thereby putting the safety of occupants at risk.

- If vessels with obstructed forward visibility do not have an effective lookout when transiting harbour areas, there is a risk that other vessels may go undetected, thereby increasing the risk of collision.

- Without an effective means to transmit a distress signal after entering the water, occupants of recreational vessels will not be able to alert others that they are in danger, which puts their lives at risk.

3.3 Other findings

These items could enhance safety, resolve an issue of controversy, or provide a data point for future safety studies.

- Wearing personal flotation devices, the proximity of other vessels to the occurrence location, and the engagement of the engine cut-off switch contributed to the survival of the pleasure craft’s 3 occupants.

4.0 Safety action

4.1 Safety action taken

Following this occurrence, Granville Island Boat Rentals reviewed its renter check-in and familiarization process. Employees now emphasize to renters the need to pay attention to surrounding vessels and give way to large commercial vessels, especially in the vicinity of bridges in Vancouver Harbour. In addition to renters watching the training video in the rental office, the video is also now available to view in advance on the company website.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s investigation into this occurrence. The Board authorized the release of this report on 26 June 2024. It was officially released on 14 August 2024.