Uncontrolled movement of railway equipment

Canadian National Railway Company

Remote control locomotive system

2100 west industrial yard assignment

Mile 23.9, York Subdivision

MacMillan Yard

Vaughan, Ontario

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

On 17 June 2016, at about 2335 Eastern Daylight Time, the Canadian National Railway Company (CN) remote control locomotive system 2100 west industrial yard assignment was performing switching operations at the south end of CN's MacMillan Yard, which is in the Concord industrial district of Vaughan, Ontario. The assignment was pulling 72 loaded cars and 2 empty cars southward from the yard onto the York 3 main track in order to clear the switch at the south end of the Halton outbound track to gain access to the west industrial lead track (W100) switch. The assignment helper attempted to stop the assignment to prepare to reverse into track W100, in order to continue switching for customers. However, the assignment continued to move. It rolled uncontrolled for about 3 miles and reached speeds of up to 30 mph before stopping on its own at about Mile 21.1 of the York Subdivision. There were no injuries. There was no release of dangerous goods and no derailment.

1.0 Factual information

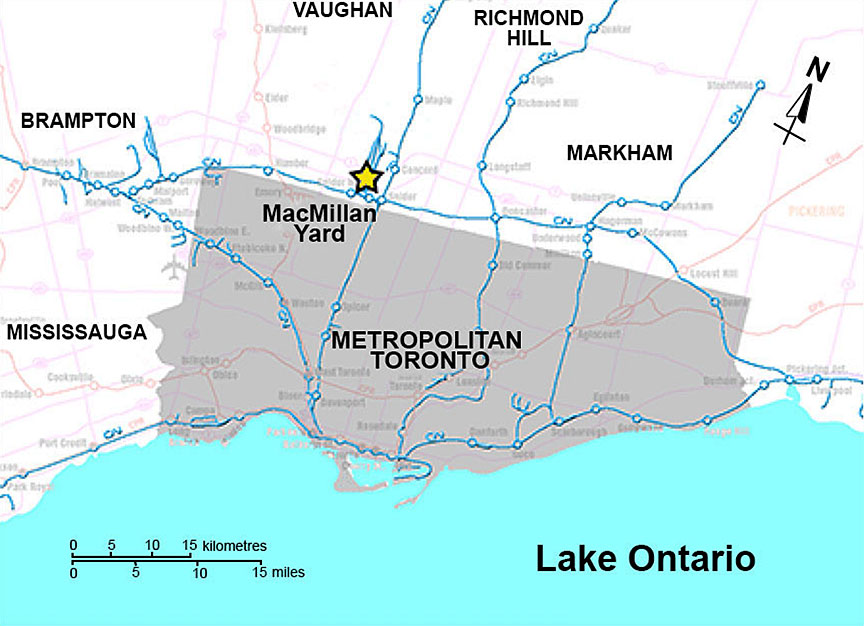

On 17 June 2016, the Canadian National Railway Company (CN) remote control locomotive system (RCLS) 2100 west industrial yard assignment was performing switching operations at the south end of MacMillan Yard. The yard is located in the Concord industrial district of Vaughan, Ontario, in the Greater Toronto Area (Figure 1). At the time of the occurrence, the assignment consisted of 2 head-end locomotives (CN 7230 and CN 207) and 74 cars (72 loaded and 2 empty cars). The first car behind the locomotives was dangerous goods tank car UTLX 208275, which was loaded with a flammable liquid (UN3475).Footnote 1 Locomotive CN 7230 was set up to operate using RCLS. Including the locomotives, the assignment was 4537 feet long and weighed 9116 tons (Appendix A).

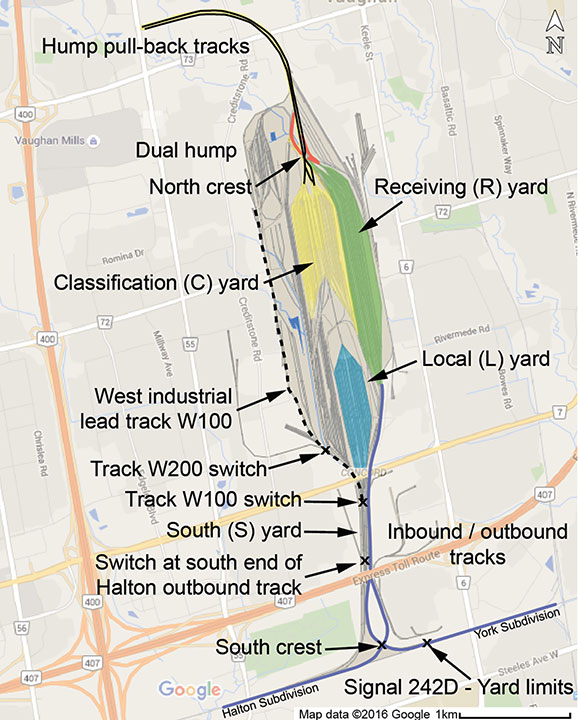

MacMillan Yard (Figure 2) is CN's main classification yard in Eastern Canada, where rail traffic is distributed by flat switching or "humping"Footnote 2 rail cars into various tracks for placement on different trains. MacMillan Yard operations are conducted under Canadian Rail Operating Rules (CROR) Rule 105. Train movements are restricted to speeds of up to 15 mph and must be able to stop within half the range of vision of equipment. The yard processes up to 1 million cars annually.Footnote 3 On any given day, there are 15 to 20 assignments working in the yard. There are up to 150 operating employees working at various jobs (local, yard, humping operations) at MacMillan Yard. Most MacMillan Yard assignments and some work assignments are operated by 2 qualified conductors, each equipped with an RCLS Beltpack,Footnote 4 enabling either crew member to control the locomotive.

In this occurrence, the assignment crew consisted of a foreman, who was in charge of coordinating the switching activities, and an assignment helper. Both crew members were qualified for their positions and met fitness and rest standards.

They were assisted by a trainmaster. Trainmasters oversee MacMillan Yard operations. Their duties include

- ensuring train crew compliance with the CROR and CN's General Operating Instructions (GOI),

- working with locomotive engineers (LEs) and conductors to make sure that trains are on time, and

- conducting job briefings with all crews at the start of their shift. This normally consists of a brief conversation in person or by telephone to discuss work for the day and focuses on safety, for example, by highlighting recent occurrences. Crews usually print their own paperwork, although trainmasters may occasionally provide a switch list with instructions for the crew.

1.1 The incident

At about 2030Footnote 5 on 17 June 2016, the assignment crew foreman and assignment helper reported for work at MacMillan Yard. The foreman had expected to work as a yard helper. However, because the regular foreman for the west industrial yard assignment was on vacation, the employee was designated the foreman for that assignment.

The crew did not have much experience working on this particular assignment, so the foreman contacted the trainmaster by telephone and requested a more detailed job briefing. The trainmaster advised the crew to first review the west industrial job aid booklet, which included a customer map of the west industrial lead track (W100) as well as customer spotting requirements.

At about 2050, the trainmaster met with the assignment crew for the job briefing and provided the crew with a marked-up switch list. The trainmaster and assignment crew reviewed the job aid and discussed the preferred method for building the assignment, because the required setup was different from most other MacMillan Yard assignments. They reviewed how to build the setup of cars, looked at the tracks involved, and discussed the work and the various ways that it could be completed.

While discussing the workload, the trainmaster referred to the west industrial job aid, particularly page 82, which detailed how to build the setup to facilitate switching the west industrial lead from the south. The trainmaster read aloud the train build, as itemized, and identified that the cars on both the north end and the south end of the movement would require air. The trainmaster instructed the crew to

- build the train setup for south control,

- put air on the cars listed,

- take their spots to the W100,

- do both the spots and pulls on the W100 and W200 first, and

- do the south yard (S-yard) pull last.

After the initial job briefing, the trainmaster drove the crew members to their locomotives. Before the crew members got out of the trainmaster's vehicle, the trainmaster conducted a second job briefing, reminding the crew to refer to the job aid and reiterating the switching and air brake requirements. During the job briefings, neither the length and tonnage of the assignment nor the risks associated with moving all 74 cars to the west industrial yard in a single move were discussed.

Upon completion of these job briefings, the trainmaster believed that a specific reference to the need to spot some customers' cars with operative freight car air brakes made it clear that air should be run through the entire train air brake line before the assignment proceeded to track W100, so that all equipment would have operative air brakes. However, the crew understood this to mean that air must be applied only to the specific cars mentioned before they were left at some customer facilities.

The crew members then boarded the lead locomotive, armed the Beltpack, and carried out the preliminary inspection and tests. At about 2120, the crew members went to the local yard (L-yard) to build the assignment. They began pulling cars from different tracks to assemble the train in order to facilitate the spotting of cars at various customer facilities. The crew coupled the air hoses on some portions of the assignment but planned to finish coupling the air hoses and to charge the train brakes after moving to the west industrial tracks. Consequently, there were no air brakes on any of the cars.

The assignment crew planned to pull all the cars at once, which required the assignment to access the York Subdivision main track in order to clear the switch at the south end of the Halton outbound track. Once the assignment had cleared the switch, the assignment crew planned to reverse the assignment into track W100 to gain access to customer locations on the west side of the yard. The crew also intended to supply air to the head-end cars (south end) that needed air brakes before delivery to customers once the assignment had reversed into track W100.

At approximately 2335, the assignment had been assembled and began pulling 74 cars southward from the yard onto the York 3 yard track. The assignment helper was positioned on the locomotive platform and was controlling the assignment using a Beltpack while the foreman, also with a Beltpack, was positioned on the ground at the switch at the south end of the Halton outbound track. Because of the weight of the assignment and the ascending 0.35% grade, the assignment initially had difficulty moving and could reach a speed of only about 4 mph while pulling southward.

At 2340:26, the assignment stopped at Signal 242D, located at Mile 24.2 of the York Subdivision, to wait for eastbound intermodal train Q120 to arrive and pass. The crew waited for a permissive signal indication that would allow them to access the York Subdivision main track, because they needed to move eastward on the York Subdivision to be able to clear the switch at the south end of the Halton outbound track.

At 2359:22, train Q120 had passed, and the assignment helper received a permissive indication and began to pull the assignment forward while the foreman communicated over the radio the distance required to clear the switch. After the assignment had reached a speed of about 8 mph, to prepare to stop the assignment at the request of the foreman, the assignment helper applied the locomotive independent brake and reduced the Beltpack speed selector to the "Coast B" position, then the "Coast" position.Footnote 6 However, the assignment continued to move, and the helper realized it was unable to stop.

After the assignment had travelled about 2000 feet, the assignment helper placed the Beltpack brake selector in the emergency position. Since there was no supply of air in the train air brake line, emergency brakes were not available on any of the freight cars, and the assignment continued to accelerate. The helper advised the foreman that the assignment was uncontrolled. The foreman made an emergency radio broadcast and called the rail traffic controller (RTC).

The RTC immediately protected the uncontrolled movement by lining the power switches from the York Subdivision to the Bala Subdivision, where there were no conflicting movements. The assignment continued to roll uncontrolled, reaching a speed of almost 30 mph.

At 0014:25, the assignment came to a stop on an ascending grade at Mile 21.1 of the York Subdivision before accessing the Bala Subdivision.

At the time of the incident, the sky was clear, winds were 12 km/h from the northeast, and the temperature was 21 °C.

1.2 Subdivision information

The CN York Subdivision extends from MacMillan Yard (Mile 25.0) to Pickering Junction (Mile 0.0). There are multiple main tracks from Mile 25 to Mile 23.92, double main track from Mile 23.92 to Mile 12.33, and single main track from Mile 12.33 to Mile 0.0. Train movements are controlled by the centralized traffic control system (CTC), as authorized by the CROR, and supervised by an RTC located in Toronto. The junction switch for the Bala Subdivision is at Mile 18.72.

1.3 MacMillan Yard track profile

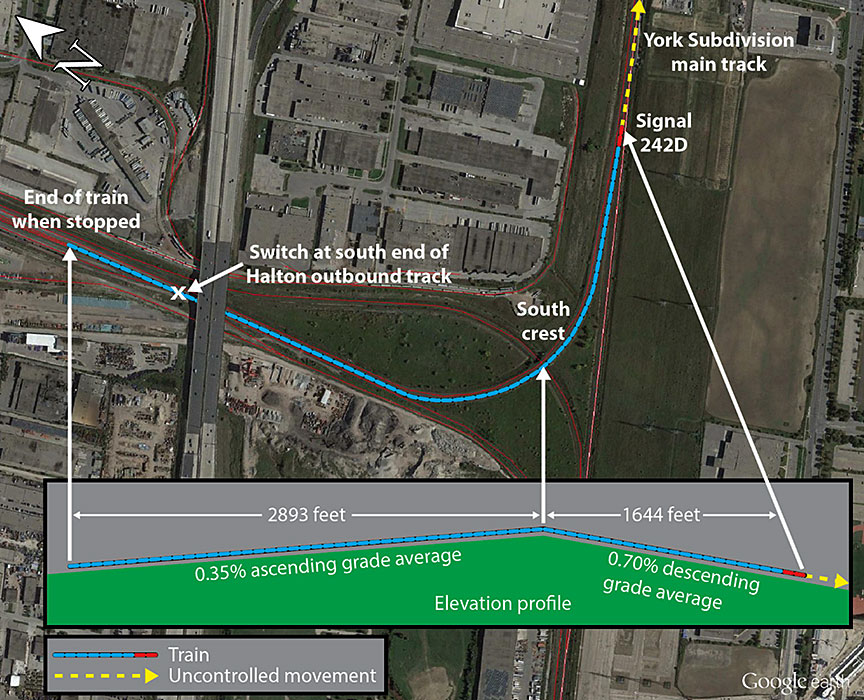

Yards are generally designed with a bowl-shaped profile to protect against freight cars rolling uncontrolled onto the main track during switching and/or humping operations. MacMillan Yard has a descending grade from both the north and south end of the tracks toward the centre of the yard, giving it such a bowl-shaped profile. At the south end of the yard, the south crest of the bowl is located 1644 feet west of Signal 242D (Figure 3), on top of the Halton Subdivision railway overpass. There is a 0.35% ascending grade for trains approaching the south crest from the north. There are no signs identifying the location of the south crest to train or assignment crews. Over the crest, there is an eastward 0.70% descending grade approaching Signal 242D and extending onto the York Subdivision.

1.4 Hump assignments

Humping and switching operations are carried out mainly at the north end of MacMillan Yard, where the classification tracks and receiving yard are located. Other RCLS assignments work in other parts of the yard and service some nearby customers.

At the north end of the yard, there are 3 dual-control hump RCLS assignment crews working each day, consisting of 1 foreman each; the remainder of the RCLS yard assignment crews operate as 2-person crews. The crews working at the north end of the yard generally switch short cuts of cars without the use of air brakes. Because cars are protected by the bowl-shaped topography of the yard, crews allow them to move under their own momentum. These yard crews do not usually access the main track to perform their regular duties.

1.5 West industrial yard assignment

The west industrial yard assignment operates 7 days a week in CN's MacMillan Yard. Reporting at 2100 daily, the assignment crew spots and lifts freight cars from customer facilities along the industrial tracks on the west side of MacMillan Yard. The crew typically receives a switch list, builds the train in the southeast portion of the yard, and then proceeds to the west industrial tracks via track W100. Most customers are serviced in the west industrial yard while the assignment is shoving northward. This area of the yard is not typically used by other assignments.

At the beginning of the shift, the assignment foreman receives a list of cars that need to be delivered to customers. The crew then proceeds to the L-yard to assemble the cars, which are placed in an order that facilitates the switching work to be performed later. Since some customers require air brakes when the cars are left at their facilities, those cars are placed next to the locomotives. At the discretion of the foreman, the train air brake line can be coupled and charged when assembling the train in the L-yard or once the cars have been shoved onto track W100.

The amount of switching performed each day depends on the number of cars to be delivered to customers, so the workload can vary. When the assignment is pulled from the L-yard to access track W100, it must clear the switch at the south end of the Halton outbound track. There is room for approximately 52 cars (3100 feet) between the switch and Signal 242D. If the assignment does not have enough room to clear the switch, the crew can either ask for a permissive signal and enter the York Subdivision to gain more track or move the cars to track W100 in separate cuts.

1.5.1 Regular foreman on the west industrial yard assignment

The regular foreman on the west industrial yard assignment was one of the most senior employees at MacMillan Yard, with 30 years of experience. This foreman had worked on the assignment since 2008 and had developed the west industrial job aid. The foreman's typical days off were Thursday and Friday. On these days, and at other times when the regular foreman was not available, the assignment was staffed from the yard spare board.

The regular foreman usually limited the cut of cars taken to the west industrial tracks to 60 cars and rarely accessed the main track to complete switching. If more than 60 cars were required, they were taken to the west industrial yard in multiple trips. When building a setup of any length, the regular foreman placed cars to be spotted with air at the head end of the assignment and charged those cars with air before proceeding to the west industrial tracks. This provided additional freight car air brakes to assist in controlling the assignment while the crew spotted other cars that required air. It also allowed cars that did not require air to be "kicked" or switched at the customer facility.

In the past, trainees were assigned to work on the west industrial yard assignment as part of their on-job training so that they could benefit from the regular foreman's knowledge and experience. However, due to the workload of the assignment, the time that trainees could spend using a Beltpack was sometimes limited. Following several conflicts with trainees over following proper procedures, the regular foreman had refused to accept trainees for more than 2 years before this incident. During this time, CN management assigned trainees to the west industrial job on the regular crew's days off, in an effort to provide trainees with some experience on the assignment. However, on such days, there was often less traffic, resulting in shorter trains, and the trainees did not go to all customers in the industrial yard. Consequently, during these 2 years, trainees received very little exposure to the west industrial yard assignment.

1.5.2 West industrial job aid

Most job aids for MacMillan Yard are kept in the CN Greater Toronto Area Job Aids Manual. The regular foreman produced a job aid to assist other crews in performing the duties of the west industrial yard assignment. The document described the preferred order for building the train before proceeding to the west industrial tracks. The job aid described the logistics of setting up movements as well as spotting and lifting cars in customer tracks. This included locations where cars were required to be spotted with air brakes applied. The job aid provided the following guidance for building the setup:

Building your setup at south

Ideally, when building the setup at south it is best to build in the following order although it can be varied to accommodate what customer have to be serviced.

From north to south:

- Norampac

- BWW 142

- BWW 141

- Steel centre

- Lumber bulkheads

- Lumber boxcar

- Metro

- Axiall

- KIK

The KIK, Axiall, Metro and Lumber would have air in them.

This will allow you to kick the Norampac and BWW cars into the clear track in the support yard on the W100 as they will need to be runaround to spot from the other end. Cars can be kicked in at 4mph and will roll in nicely. The steel can then be shoved into W116 or W115. If you need to go up the W200, then the Metro and Lumber cars can be set out of the way. The W200 can be done. Rehumps put into W117 and grab the Metros and Lumber. Afterwards Norampac can be pulled and doubled to the BWW's, put in W117 and take the loads and spot.Footnote 7

The job aid did not

- suggest limits on the number of cars that could be moved to track W100 in a single cut;

- suggest limits on tonnage and length of assignments that could be moved to track W100 in a single cut;

- specifically state when air should be applied through all or part of the assignment to assist with train control when accessing the main track and/or proceeding to the west industrial tracks via track W100; or

- provide the location of the south crest of the yard or discuss the effect of the 0.70% descending grade extending southward from the crest to the York Subdivision main track.

1.5.3 South yard job aid

For comparison, the S-yard job aid provides the following guidance for assignments switching in the S-yard:

S Yard

The switch to access S-yard is the tall stand switch located just north of the Hwy 407 overpass on the Halton outbound. There is a steep grade in all directions from the switch at the top of the hill, so caution should be used when in S-yard. The pullback continues all the way back to the signal at Snider West and is protected just before the light by a derail. It is good for 40-50 cars.

It is an extremely steep grade and when pulling cars from S031, air MUST be applied to the cars and a MAXIMUM of 18 cars can be pulled back at one time. Due to the varying length of the cars for S042, when handling loads onto the pullback, the movement should be kept to about 14 cars at a time WITH AIR, exercising caution and keeping the movement as close to the switch as possible. This movement MUST be pulled back at a speed that will allow stopping as close to the switch as possible. If the cut is pulled back too far, the engine will not be able to shove it up the hill due to the grade.Footnote 8

1.6 Rules and instructions on use of air brakes when operating remote control locomotive systems

Most switching operations in MacMillan Yard are performed without the use of train air brakes, and crews put air on cars only when customers specifically require this.

The CROR recognize that rules cannot cover all situations and that train crews must exercise some judgment to provide safe operations. Specifically, CROR Rule 106 (Crew Responsibilities) states the following:

Footnote 9The CROR provide for circumstances in which train air brakes are required for transfer movements. Specifically, CROR Rule 64 states the following:

64. TRANSFER REQUIREMENTS

- The locomotive engineer must verify that there are sufficient operative brakes to control the transfer, confirmed by a running test as soon as possible.

- Except where cautionary limits or block signals provide protection, transfers must have air applied throughout the entire equipment consist. The last three cars, if applicable, must be verified to have operative brakes.

- A transfer carrying dangerous goods must have air applied throughout the equipment when operating within any method of control.

- Remote control locomotives in transfer service may only operate on the main track when a qualified operator is equipped with an operative operator controlled unit (OCU). Each qualified operator, to a maximum of two, must have an operative OCU.Footnote 10

However, the movement in this occurrence was not considered a transfer movement described under CROR Rule 64, according to CROR Rule 65:

65. ENGINE IN YARD SERVICE REQUIREMENTS

An engine in yard service that is required to enter main track to double over, take head room or cross over a main track will not be considered a train or transfer except in application of Rules 301-315 and 560-578.Footnote 11

The CROR requirements for air brakes on transfer movements are reiterated in CN's GOI:

Sufficient braking effort to control the movement confirmed by a running brake test as soon as possible. Transfers operating in OCS territory, or carrying Dangerous goods must have air applied throughout the equipment. The last three cars, if applicable must be verified to have operative brakes on Transfers operating in OCS territory.Footnote 12

With respect to transfer movements, the GOI further state that

Prior to departure, the Locomotive Engineer or the Remote Control operator must verify that there is sufficient braking effort to control the transfer as determined by a running brake test.Footnote 13

The GOI define a running brake test as a "test of brakes performed on a moving train to ascertain the brakes are operational."Footnote 14

Section 6 of the GOI, Remote Control Locomotives, does not state when air brakes are required to be cut in and does not specify any restrictions on the number of cars or tonnage that may be handled by an RCLS operator.Footnote 15

No guidance in CN's GOI or the CN Macmillan Yard Operating Manual required the movement in this occurrence to be conducted using train air brakes, even when accessing the main track.

1.7 Assignment crew and trainmaster experience

At the time of the incident, both members of the assignment crew were generally unaware of the location of the south crest of the MacMillan Yard bowl, and the effect that the train length and tonnage could have on train handling while descending a 0.70% grade with only locomotive independent brakes available to control the assignment.

As conductors, the assignment crew had received little training on train handling,Footnote 16 and such training was not required.

1.7.1 Assignment foreman

The assignment foreman had started conductor training in February 2014 and had qualified as a conductor in August 2014, after having completed approximately 70 training trips. At the time of the occurrence, the assignment foreman had about 22 months of continuous service as a qualified conductor with CN.

The foreman had worked on the assignment twice as a trainee. Since qualifying as a conductor, the foreman had worked as a helper on the west industrial yard assignment fewer than 5 times and was expecting to work as a helper on the night of the occurrence.

1.7.2 Assignment helper

The assignment helper had started conductor training in July 2014 and had qualified as a conductor in January 2015, after having completed approximately 70 training trips. At the time of the occurrence, the assignment helper had 17 months of service as a qualified conductor with CN. However, during that time, the helper had been laid off on 2 occasions, for a total of 4 months. The helper had returned from the last layoff in May 2016, about 1 month before the occurrence.

The helper had worked on the assignment twice as a trainee. Since qualifying as a conductor, the helper had worked on the assignment about 11 times as a helper. However, the helper had not worked on the assignment since returning from layoff in May 2016.

1.7.3 Trainmaster

On the night of the occurrence, the trainmaster on duty worked a shift from 1800 to 0600 and was the only trainmaster on duty in the yard. The trainmaster had about 25 years of experience with CN and had worked in car control, customer service, risk management, and accounting before working as a trainmaster. The trainmaster had about 12 years of operational experience and was qualified as an LE, a conductor, and an RCLS operator.

1.8 Operational experience

Knowledge, skill, judgment, and experience are critical factors that directly affect an operating crew's ability to operate safely. Operating crews that work in yards must understand the nuances of switching manoeuvres directly affected by train length, tonnage, and speed, and must be able to control a train using automatic air brakes, locomotive independent brakes, or a combination of both. To accomplish this, hands-on experience with operating equipment and familiarity with the topographic features of the territory are essential.

1.8.1 Crew experience and familiarity with MacMillan Yard

Work on available local assignments was posted for bidding. The positions were awarded to the most senior employees who had submitted bids. Some positions were more desirable than others because of the rate of pay, days off, and hours of work. Typically, the evening and night shifts were the least desirable. Yard positions are often regarded as the least desirable, as the pay rates are the lowest.

When no job bids were received for a specific position, the position was normally awarded to employees with the least seniority. As a result, it was not unusual for 2 junior employees at a terminal to be paired together to work yard assignments, particularly during the evening and night shifts. In this occurrence, although both west industrial yard assignment crew members were qualified, they had limited experience working on that assignment. In contrast, companies in other transportation industries, such as aviation, have policies in place to minimize the risk that 2 operators with limited experience on a given route or task will work together.Footnote 17

To assess the effect that experience (seniority) had on familiarity with MacMillan Yard, RCLS and conductor training, and the west industrial yard assignment work, TSB investigators conducted interviews with 15 RCLS-qualified conductors, which included the assignment crew. This represented a 10% sampling of all MacMillan Yard operating employees. The following observations were made:

- The challenges of the west industrial yard assignment intimidated many of the less experienced conductors, who sought to avoid it when possible.

- More experienced qualified RCLS conductors who had worked on the west industrial yard assignment preferred to move the cars to track W100 in 2 separate cuts.

- During RCLS training, the trainers often took control of the RCLS equipment to ensure that yard productivity requirements were met.

- During the initial week of RCLS training, locomotives were not always available; therefore, some trainees received limited practical training.

- Newly qualified conductors were regularly required to train new trainees.

Seven of the 15 conductors interviewed had less than 28 months of operational experience at MacMillan Yard (Appendix B). The following observations were made about these conductors:

- When working as trainees in MacMillan Yard, all 7 conductors reported that they had received training from newly qualified conductors ("green vests").Footnote 18

- The first day that 2 of the conductors were deemed fully qualified, they were tasked with supervising another trainee. In both of these cases, the employees refused because they did not feel they had sufficient experience in the yard.

- When working as trainees, 4 of the 7 conductors never received training on the west industrial yard assignment, and the remaining 3 had trained on that assignment only a few times. As a result, all 7 had little operational experience on that assignment.

- Newly qualified conductors intentionally avoided the west industrial yard assignment because they did not feel adequately trained for it.

- At least 4 of the 7 conductors, including the assignment crew involved in this incident, did not understand the effect that an assignment's length and weight had on train handling when using only locomotive independent brakes to control an assignment.

1.9 Remote control locomotive system

The RCLS consists of 3 components:

- a remote control locomotive(s) (RCL);

- an onboard control computer, mounted inside the RCL to interface with the controls; and

- an OCU, commonly referred to as a Beltpack. The OCU is a lightweight remote-control device that attaches to the operator's safety vest.

Crew members can pass control of the locomotives back and forth as required ("pitch and catch"), but only 1 crew member can have control at a time. Either operator can activate an emergency brake application at any time, whether or not the operator is in control.

The OCU is equipped with (but not limited to) a speed selector, a forward and reverse selector, and a brake selector that includes an emergency brake feature (Figure 4 and Figure 5).

Beltpack operators choose a pre-selected speed of up to 15 mph, after which the operator does not have to manipulate the controls, as the RCLS takes the required actions to reach and maintain that speed. The system applies either the throttle or the brakes of the locomotives to maintain the pre-selected speed at ± 0.5 mph. The system adapts to train and terrain characteristics reactively, without taking the train length, tonnage, or slack into account.

1.10 Canadian National Railway Company use of remote control locomotive systems

Historically, a yard crew consisted of 3 employees, including an LE, a yard foreman to coordinate yard movements, and a yard helper. The yard foreman and the helper provided yard movement instructions by radio to the LE, who controlled the locomotive.

RCLS operations were introduced in Canada in the late 1980s. This technology was approved by Transport Canada (TC), and its use is governed by the CROR. It was initially used only during humping operations at CN. However, in the mid-1990s, its use was expanded to flat switching in CN yards and, in certain circumstances, on the main track. The introduction of RCLS operations eliminated the role of the LE in yard operations. Control of the locomotive became the responsibility of a yard foreman and/or a yard helper, who were typically qualified conductors.

MacMillan Yard was one of the original locations where RCLS operations were implemented. All switching assignments at MacMillan Yard are RCLS operations. Some yard assignments also travel on the main track using RCLS, to transfer from one yard to another or to travel to a customer siding to perform switching. The speed on RCLS yard assignments is limited to 15 mph, and the CROR restrict RCLS locomotives operating as a transfer on the main track to 15 mph as well. However, there are no tonnage or length restrictions.

1.11 Canadian National Railway Company remote control locomotive system training

Operating employees generally prefer road work (main-track trains) to yard work and tend to transfer to a terminal that offers road work as soon as their seniority permits. With the exception of those who have chosen to remain at MacMillan Yard because they prefer the regular schedule that yard work affords, operating employees working at MacMillan Yard tend to have less service and experience.

New CN operating employees must first qualify as conductors. Since all assignments at MacMillan Yard operate using RCLS, new hires receive their RCLS training in conjunction with the regular conductor training program.

The CN conductor training consisted of the following components:

- 7-week orientation and rules training;

- 1 week of Beltpack training;

- a minimum of 60 trips under the guidance of a qualified conductor; and

- 2 personal training days when the trainee conducts switching in a controlled environment and is evaluated by a trainer.

The Beltpack training portion was made up of a classroom component and a practical component under the supervision of an instructor. Once the classroom and practical components were completed successfully, trainee conductors put their knowledge into practice by working with regular RCLS assignments. The on-job training trips were divided between freight service (main-track) and yard RCLS assignments. CN conductor training continues until the conductor trainee is deemed qualified by a local manager, which usually takes about 5 to 7 months.

1.12 Training and qualification of railway operating employees

1.12.1 Railway Rules Governing Safety Critical Positions

The TC-approved Railway Rules Governing Safety Critical Positions were developed pursuant to section 20 of the Railway Safety Act.Footnote 19 Section 3 of those rules states the following:

A "Safety Critical Position" is herein defined as:

- any railway position directly engaged in operation of trains in main track or yard service; and

- any railway position engaged in rail traffic control.

Any person performing any of the duties normally performed by a person holding a Safety Critical Position, as set out in section 3 above, is deemed to be holding a Safety Critical Position while performing those duties.Footnote 20

1.12.2 Canadian Railway Employee Qualification Standards Regulations

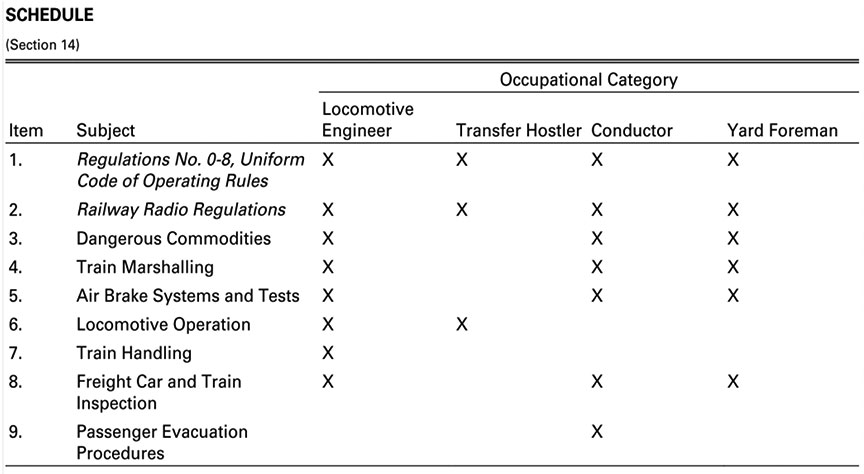

In Canada, federally regulated railways must abide by the Railway Employee Qualification Standards Regulations,Footnote 21 issued in 1987. These regulations establish the minimum qualifications for LEs, transfer hostlers, conductors, and yard foremen. They apply to all railway employees performing the duties of the specified occupational category, whether or not the employee is unionized. An excerpt from the regulations is provided in Appendix C.

Since the regulations came into force, there have been significant operational changes within the rail industry, including the following: crew size has been reduced, RCLS operations have been widely implemented across the country, and the use of management crews qualified through accelerated training has become common at both CN and Canadian Pacific Railway (CP). Despite these significant changes in railway operations, the regulations have not been modified in over 31 years.

When the regulations came into effect, most railway operating employees were unionized, and the use of management crews was not widespread. At that time, there was a graduated promotion from unionized brakeman / yard helper to conductor / yard foreman and then to LE. As the industry and the technology evolved, the role of brakeman was eventually eliminated, 2 years of experience as a brakeman was no longer required, and all new operating employees were hired as conductors. As a result, new unionized employees were considered to be qualified as yard helper, conductor, and yard foreman as soon as they completed their conductor training course.

Although the regulations require railway companies to file and report to TC information on their employee qualification program and any changes made to the program, the filings can be in the form of a summary and do not necessarily include all course content. While TC may occasionally conduct a cursory review of company submissions, the regulations do not require TC to review course content in detail or approve the content.

Over the years, training delivery has changed, and unionized conductor training has been accelerated to the point that some new conductor candidates can now qualify within 6 months.

Subsection 19(2) of these regulations requires that a railway company establish and modify its employee training programs in consultation with the trade unions representing its employees in the respective occupational categories. Therefore, qualification requirements such as course content, experience required for qualification (time served in the trade or number of trips), and graduated qualification for unionized candidates in all occupational categories are negotiated between the company and the respective trade unions.

1.12.3 Locomotive engineer training

Operating a locomotive is a complex task, and LEs are trained to recognize the characteristics of the train they are operating, such as length, tonnage, and weight distribution within the train. They must also know the characteristics of the territory (i.e., undulating terrain, grade, and curvature) in which they are operating. LEs must anticipate the train's response and adapt its operation to negotiate changes in terrain as well as to comply with signal indications and RTC instructions. To do this, they use the throttle and brakes. In addition, to reduce the forces in-train and between the train and the track, changes to the train speed must be planned and gradual. Under the regulations, LEs are also required to receive recurrent training in locomotive operation and train handling.

1.12.4 Conductor training

The regulations do not require conductors to receive training on locomotive operation or train handling, which would include considerations for tonnage distribution within a train or assignment, the topography of a given area, and the effect it can have on handling and maintaining control of a train.

1.12.5 Training of other railway employees

Training for unionized operating job categories such as RCLS operators and RTCs is not covered by the regulations, but most railways have training plans and manuals in place for those positions. The regulations also contain no minimum experience or course content requirements to carry out the duties of a management LE, conductor, or foreman.

CN encourages operations managers to be qualified in the running trades as conductors or LEs and provides incentives for management crews to maintain their qualifications. All other CN non-union employees are expected to become qualified conductors or LEs unless they are medically unfit to do so. CP has similar practices.

Both railways now periodically use management crews to operate trains at various terminals when necessary. Management crews can be sent to any terminal on the railway network during shortfalls in staffing in a service area.

CN's training for unionized and management railway operating employees met current regulatory requirements.

1.12.6 Railway Safety Act Review panel final report (2007)

In December 2006, the Minister of Transport, Infrastructure and Communities initiated the Railway Safety Act Review. The review was aimed at identifying gaps in the Railway Safety Act and making recommendations to strengthen the regulatory regime to meet the changing nature of the railway industry and its operations. In November 2007, the Railway Safety Act Review panel issued its final report, entitled Stronger Ties: A Shared Commitment to Railway Safety – Review of the Railway Safety Act.

Section 9.5 of the report dealt specifically with training for operating crews and stated, in part,

In the United States, the FRA [Federal Railroad Administration] certifies all locomotive crews. As well, the Department of Transportation in the U.S. certifies all aviation and marine crew members. In Canada, Transport Canada also certifies all aviation and marine crew members, but there are no provisions for Transport Canada certification of railway operating employees.

Transport Canada, Rail Safety Directorate has programs in place to address the qualifications of locomotive crews and rail traffic control positions. Nonetheless, there is a perception that because sole responsibility for certification of the candidates rests with the industry, there may not be sufficient objectivity. While consideration was given to recommending alternative approaches to the certification of the running trades, we understand that the current regulation will be superseded by new training rules and that these rules will address this issue.Footnote 22

Consequently, the Railway Safety Act Review panel did not issue a recommendation relating to operating crew training.

In recognition that the regulations were out of date and to help address some of the operational changes that had occurred since the regulations were issued, the railway industry, including the Railway Association of Canada, drafted the Rules Respecting Minimum Qualification Standards for Railway Employees. In 2009, the rules were submitted to TC for approval. Although TC initially approved the rules, the regulations were never repealed. Consequently, the regulations remain in force to this day.

1.12.7 Regulatory requirements for operating crews in the United States

Railways in the U.S. are required to ensure that only employees who meet the minimum federal safety standards serve as LEs and conductors. These federal safety standards are specified in the U.S. Department of Transportation Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Title 49,Part 240: Qualification and Certification of Locomotive Engineers (October 2012) and Part 242: Qualification and Certification of Conductors (October 2012). The FRA is responsible for the oversight and enforcement of these regulations.

The standards prescribe the minimum federal safety standards for the eligibility, training, testing, certification, and monitoring of operating employees but do not restrict a railway from adopting and enforcing more stringent requirements. Appendix D provides a summary of the U.S. regulations for operating crews.

1.12.8 Railway Safety Management System Regulations, 2015

On 01 April 2015, the Railway Safety Management System Regulations, 2015 (SMS Regulations) came into force and replaced the 2001 SMS Regulations. Many of the changes incorporated into the revised SMS Regulations responded to the recommendations from the Railway Safety Act Review in 2007 and from a study on rail safety by the Standing Committee on Transport, Infrastructure and Communities in 2008.

Under these regulations, federally regulated railway companies must develop and implement an SMS, create an index of all required processes, keep records, notify the Minister of proposed changes to their operations, and file SMS documentation with the Minister when requested.

Paragraph 5(k) and subsection 28(1) of the SMS Regulations state, in part, that a railway must have a process with respect to scheduling. The scheduling process outlined in the regulations requires that the company apply the principles of fatigue science when scheduling the work of the operating employees. There is no requirement to consider the experience of operating employees who may be paired together for work.

With regard to crew training, sections 25 to 27 of the SMS Regulations require a railway to have a process for managing knowledge. A railway company must establish a list setting out

- the duties that are essential to safe railway operations;

- the positions in the railway company that have responsibility for the performance of each of those duties; and

- the skills and qualifications required to perform each of those duties safely.

A railway company must also include in its SMS a plan for ensuring that an employee or supervisor who performs any of the duties in the list has the skills, knowledge, and qualifications required to perform his or her duties safely, as well as a method for verifying this.

In accordance with these sections of the regulations, CN had a process document outlining its plan for managing knowledge. The document contained the lists required by subsection 25(1) and the plan and methods required by section 27. In addition to the conductor, LE, and Beltpack operator positions, the CN list included other operational positions. The SMS Regulations do not require individual plans and methods for each position and do not prescribe the training requirements to qualify for each position.

With regard to employees performing train operations, CN identified the duties essential to safe railway operations and the positions performing the duties:

- Operating a train: Conductor

- Operating a locomotive: LE, Beltpack operator, conductor locomotive operator, and hostler

- Controlling train movement: RTC

For each position, the skills and qualifications required to perform essential duties were listed in a document that also outlined the training requirements for the positions. A review of the document revealed that

- conductors have to requalify every 3 years, but there is no practical component required to requalify;

- conductors and RCLS operators do not receive train simulator, train handling, or locomotive operation training;

- there is no requirement for RCLS operators to requalify in Beltpack operation; and

- RTCs must requalify every 3 years, but there is no practical component required to requalify.

Since the SMS Regulations came into effect in 2015, there have been 2 TC audits of CN's plans and methods associated with sections 25 to 27. The first audit was a regional, targeted audit, which focused on qualifications of signal employees who install and test signal devices. The second audit was a corporate audit, which included the skills and qualifications of operating crews.

In comparison, CP had a detailed list of essential duties for LEs and conductors, and a process for ensuring and verifying the required skills and qualifications for the performance of their duties essential to safe railway operations. However, CP did not have such a list or process for RCLS operators and related Beltpack operations. While CP conducted RCLS efficiency testing in an effort to ensure that employees have the requisite skills, qualifications, and knowledge for safe operations, CP did not consider RCLS to be an essential service, and there was no reference to RCLS contained in CP's SMS plan for managing knowledge.

1.13 United States regulatory guidance for use of remote control locomotive systems

In 2002, to better understand the safety implications of remote control locomotive operations, the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) initiated a research program consisting of several studies.

As a result, in September 2005, the FRA issued the following guidelines to the railroad industry for RCLS main-track terminal operations:

- Maximum locomotive horsepower of 3,000 working HP with a maximum of 8 axles;

- Maximum train length of 1,000 feet (about 20 cars);

- Maximum train speed of 15 mph;

- Prohibited from operating on grades of 0.5 percent or greater that extended more than ¼ mile.Footnote 23

The FRA RCLS guidelines remain in effect today.

After these guidelines were issued, Union Pacific Railroad Company contracted Rail Sciences Incorporated (RSI) to further evaluate RCLS operations. RSI conducted computer simulations and recommended updates to the original FRA guidelines based on the results of its analysis. RSI provided its simulation results to the FRA in a report dated December 2006. The FRA examined the report and analysis and concluded that the analysis was complete and adequately simulated the types of operations that would be encountered in actual RCLS main-track terminal operations. The FRA supported the RSI's conclusions and recommended updated guidelines, which state the following:

- Locomotive consist should not exceed 6,000 total working horsepower, utilizing no more than 12 actual axles;

- Train length (excluding locomotives) should not exceed 3,000 feet;

- Train tonnage (excluding locomotives) should not exceed 4,000 tons;

- Train should not exceed a total of 50 conventional cars and/or platforms;

- No more than 20 multilevel (autorack) cars, regardless of whether they are loaded or empty, may be in the train. Any continuous block of more than 5 multilevel (autorack) cars must be placed at the rear of the train;

- Train speed should not exceed 15 mph;

- Movements should be restricted from operating on any grade greater than 1.0 percent that extends for more than ½ mile.Footnote 24

No such guidelines have been proposed for Canadian railways.

1.13.1 Federal Railroad Administration Final Report: Safety of Remote Control Locomotive Operations (2006)

In March 2006, the FRA published its Final Report: Safety of Remote Control Locomotive (RCL) Operations. The report identified human factors issues inherent to RCLS operations that warranted close attention as RCLS technology continued to evolve, including operator training, preparation, and experience:

Training problems were noted in the following areas:

- Lack of training for a specific move to be made or specific area of a yard.

- Inadequate on-the-job training. This includes a lack of consistency and structure in the training, and a lack of preparation for those that provide training.

- Insufficient amount of hands-on training. Some RCLS operators have reported that they did not receive enough hands-on training with the beltpack before becoming qualified as an RCLS operator.Footnote 25

The report also highlighted the potential safety implications of pairing inexperienced crew members together, given the high level of turnover expected across the rail industry.Footnote 26

In the past, many of the employees who were initially trained in the use of RCLS technology had significant railroad experience to draw on. Experienced employees were familiar with railroad safety, operating rules, and the intricacies of working within busy classification yards.Footnote 27

In its report, the FRA issued the following recommended practices in regard to training:

- Railroads should employ instructors who have as much experience and knowledge of RCLS operations as possible.

- Railroads should provide formal "train-the-trainer" courses, so that training is as effective as possible.

- The amount of on-job training should be increased to cover the entire range of locations, operations, and configurations of cuts of cars that RCLS operators will encounter on the job.

- RCLS operators should also have a minimum amount of operating experience as a switchman or engineer before becoming an RCLS operator.

- Training should incorporate train-handling methods, familiarity with and knowledge of basic locomotive systems, and safe operating practices that inform RCLS operators of what they can and cannot do.Footnote 28

In May 2006, the FRA published the Final Report: A Comparative Risk Assessment of Remote Control Locomotive Operations Versus Conventional Yard Switching Operations. The objective of this study was to obtain a better understanding of remote control locomotive operations and their relative safety compared with conventional yard-switching operations. The study focused on yard-switching operations and did not address remote-control locomotive operations on main tracks, spur/industrial tracks, or sidings. The report noted that the FRA had only begun to collect accident data for remote control operations and that the data-collection process would require several years before sufficient data were available to analyze.

1.14 Potential gaps in regulatory oversight in Canada

The TSB reviewed historical and current railway work and training practices for unionized and management operating crews based on previous TSB reports, the Railway Safety Act Review panel final report (2007), and relevant regulations in Canada and the U.S. As detailed in the sections that follow, the TSB review identified significant gaps in the Railway Employee Qualification Standards Regulations.

1.14.1 Qualification standards

TC certifies all aviation and marine crew members, but there are no provisions for the certification of railway operating employees. The rail industry has the sole responsibility for qualification of the candidates. Since there is no independent regulatory oversight for the qualification of operating crews in Canada, there may not be sufficient objectivity concerning operating crew qualification training.

The U.S. regulations require that a practical training component be completed in order for an operating employee in any occupational category to qualify or requalify in a given position. Whereas Canadian regulations require that candidates for LE and transfer hostler positions demonstrate that they have the requisite theoretical and practical skills required to qualify initially, there is no practical training required for requalification of LEs, transfer hostlers, or conductors. The Canadian regulations contain qualification standards for on-job training instructors for LEs and transfer hostlers but no requirement for on-job training instructors for conductors or foremen. This means that an inexperienced, newly qualified conductor or foreman could be requested to act as an on-job training instructor for subsequent conductor candidates.

Furthermore, since the regulations apply only to company employees, it is difficult to ensure that contract instructors who are not company employees are qualified to deliver training or act as examiners for any occupational category.

1.14.2 Graduated qualification

In the past, there was a more graduated approach to operating crew qualification, which presented more opportunities for mentoring as new operating employees gained experience. With the loss of the brakeman position, conductors operating RCLS, and the accelerated training process, the opportunities for mentoring that previously existed within crews are now limited.

The regulations contain graduated qualification systems for unionized LEs, their on-job training instructors, and transfer hostler candidates, but not for any of the remaining occupational categories, which includes yard foreman. Consequently, some operating employees may not acquire sufficient on-job experience to work independently and safely in all situations.

1.14.3 Remote control locomotive system operations

The Railway Employee Qualification Standards Regulations came into force in 1987, before the widespread implementation of RCLS technology in the rail industry. The regulations do not contain an operational category for RCLS operators, nor do they require employees in any operational category to receive training specific to RCLS operations. Similarly, there is no requirement for RCLS operators to requalify in RCLS operation.

1.14.4 Conductors

In Canada, conductors normally operate RCLS yard assignments, using a Beltpack, within rail yards. These assignments can enter the main track to take up head room to assist with switching operations. Conductors can also operate transfers on the main track for distances of up to 20 miles at speeds of up to 15 mph, with no tonnage or train length restrictions. Conductors receive little training in locomotive operation or train handling, and the current regulations do not require such training.

Furthermore, the regulations do not require a junior employee to work with an experienced employee to enhance opportunities for mentoring. Currently, conductors with less than 2 years' experience are often paired together when working on RCLS assignment crews.

1.14.5 Management crews

Since company managers and supervisors are not unionized, they do not have to meet the same requirements for duration of training, number of trips, and experience as unionized staff.

A new manager may take accelerated training and subsequently become responsible for signing off on training and qualifying new employees, although the manager may have little experience.

Management crews can be sent anywhere in the country to make up for shortfalls in staffing in a service area. As a result, management crews may operate trains over any subdivision without having adequate familiarization training.Footnote 29

1.14.6 Rail traffic controllers

Although RTCs are involved in most aspects of train operations and are responsible for the safe movement of trains over a given territory in accordance with existing rules, bulletins, and company instructions, there is no occupational category and no corresponding training or requalification requirements for them.

1.14.7 Regulatory oversight

The regulations contain no requirements for course training material, test content, or test delivery for any of the operational categories.

U.S. regulations require course training material or tests to be reviewed, critiqued, or certified by the regulator. Canadian regulations have no such requirements. Although railways provide TC with information related to the railway training program, TC does not assess the adequacy of the railway training program and provides no further oversight with regard to the training of railway operating employees.

Operating employees can be laid off for extended periods, up to several years. Most railways, including CN, have policies in place outlining steps for familiarization or refresher training in preparation for reintegration in the workforce. However, there are no regulatory requirements for mandatory familiarization or refresher training when operating employees return to work for any of the operational categories.

1.15 TSB investigations outlining deficiencies in operating crew training regulations

Since 2002, the TSB has investigated 5 occurrences (including the fatality of a crew member) directly related to deficiencies in operating crew training and the related gaps in the regulations (Appendix E).Footnote 30

1.15.1 TSB Railway Investigation Report R02W0060

TSB Railway Investigation Report R02W0060 determined the following:

- The LE was first trained in 1976 and had never received any subsequent practical instruction on the use of locomotive high-capacity extended-range dynamic brake or the risks associated with its use in train-handling operations.

- Training for LEs had not kept pace with improvements in dynamic-brake technology and train-handling methodologies.

- The current LE training, as overseen by TC under the existing regulations, may not be adequate.

- The regulations contained no requirement for a practical component to be completed for an LE to requalify and missed an opportunity to familiarize LEs with new equipment and train-handling techniques.

TC responded to the report and indicated that, in fall 2003, it would begin a review of the Railway Employee Qualification Standards Regulations. Based on the results of the review, TC would make recommendations to the industry concerning LE training and dynamic testing.

1.15.2 TSB Railway Investigation Report R04W0035

TSB Railway Investigation Report R04W0035 determined that regulatory oversight of training and requalification of RCLS operators had not kept pace with improvements in technology and operations.

TC acknowledged that the regulations were outdated and should be revised. TC was considering creating a working group to revise the regulations.

1.15.3 TSB Railway Investigation Report R13W0260

TSB Railway Investigation Report R13W0260 determined the following:

- The conductor trainee, who was unfamiliar with the territory and working without direct supervision, misapplied a number of safety-critical operational procedures.

- Although railways file with TC a description of all employee training programs and subsequent changes related to each occupational category, the adequacy of the training programs was not assessed by the regulator.

- TC provided no further oversight with regard to the training of railway operating employees.

The investigation identified that, in 2009, TC approved the Rules Respecting Minimum Qualification Standards for Railway Employees, which were to come into force once the regulations were repealed. Under the new rules, conductor trainees would also receive on-job training under the direction of a training instructor for the duration of the training period. However, to date, the rules are not in place, and the regulations have not been repealed.

1.15.4 TSB Railway Investigation Report R15V0046

TSB Railway Investigation Report R15V0046 determined the following:

- Unlike operating employees whose primary job is to operate trains, management employees who operate trains on a part-time basis are not likely to gain the same level of experience, proficiency, and familiarity with the territory.

- The current regulatory framework does not adequately address the requirements for training, certification, and territory familiarization for railway management employees who operate trains.

1.15.5 TSB Railway Investigation Report R16W0074

TSB Railway Investigation Report R16W0074 determined the following:

- If safeguards are not in place to ensure that crews are not only qualified, but also possess sufficient operational experience, there is an increased risk for operational errors and accidents to occur.

- If the current Canadian Railway Employee Qualification Standards Regulations are not updated, gaps will remain, and TC will not be able to conduct effective regulatory oversight and enforcement of training programs for management and unionized operating crews, RCLS operators, RTCs, and contract trainers, increasing the risk of unsafe train operations.

1.16 Other TSB investigations involving training or experience while switching using remote control locomotive systems

The TSB has investigated 5 other occurrences involving RCLS switching operations (Appendix G). A review of these investigations revealed that, in 4 of the 5 cases, the inexperience of the operating crew played some role in the occurrence.

- TSB Railway Investigation Report R16W0074 determined that operating crew inexperience played a role in the occurrence.

- TSB Railway Investigation Report R07T0270 determined that crew inexperience and inadequate training contributed to the occurrence.

- TSB Railway Investigation Report R07V0213 determined that management crew inexperience, inadequate management crew training, and the implementation of an operational change related to RCLS switching operations contributed to the accident. Although a risk assessment was conducted for the change involved, it was inadequate to identify all the hazards and mitigate the risks of switching long, heavy cuts of cars on a descending grade.

- TSB Railway Investigation Report R07W0042 determined that crew inexperience, inadequate training, and some form of distraction that occurred while conducting RCLS switching operations contributed to the accident.

1.17 Best practices in developing competence

The Rail Safety and Standards Board in the United Kingdom published a guidance document entitled Good Practice Guide on Competence Development. The guide, developed in consultation with the railway industry, was intended to provide best practices for developing comprehensive systems to manage competence rather than simply ensuring compliance with regulations.Footnote 31

"Competence" refers to the overall ability to function effectively in a position and results from the combination of functional, technical, and non-technical skills. According to the guide, non-technical skills include situational awareness, decision making, and workload management, which have been shown to play a key role in incidents and accidents.Footnote 32

The Office of Rail Regulation in the United Kingdom published a guide entitled Developing and Maintaining Staff Competence. The guide recognizes that training programs should be sufficient to prepare individuals to handle expected operations and that experience, obtained under supervision, allows individuals to carry out progressively more complex tasks:

Training and development seeks to create a level of competence for the individual or team, sufficient to allow individuals or teams to undertake the operation at a basic level. Initially this will be under direct supervision, which will become less direct. Over time, as knowledge and practical experience grows, operations can be carried out at a more complex level.Footnote 33

The guide recognized that competence development is an important contributor to managing risks, specifying that the first step in developing a competence management system is to identify activities that affect operational safety and that are critical for controlling risk.Footnote 34 This will allow a combination of risk control measures to be identified and actions taken to develop competence where this is required to manage risks.Footnote 35

1.18 TSB Lac-Mégantic investigation and Recommendation R14-04

On 06 July 2013, shortly before 0100, eastbound Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway freight train MMA-002, which had been parked unattended for the night on the main track at Nantes, Quebec, Mile 7.40 of the Sherbrooke Subdivision, started to roll. The train travelled about 7.2 miles, reaching a speed of 65 mph. At about 0115, while approaching the centre of the town of Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, 63 tank cars carrying petroleum crude oil (UN 1267) and 2 box cars derailed. As a result of the derailment, 47 people were fatally injured. About 6 million litres of petroleum crude oil spilled. There were fires and explosions, which destroyed 40 buildings, 53 vehicles, and the railway tracks at the west end of Mégantic Yard. There was environmental contamination of the downtown area and the adjacent river and lake.

Since 1996, the TSB has pointed out the need for robust defences to prevent runaways, yet runaways have continued to occur in Canada. While equipment runaways are generally considered rare, they can also be high-risk events and have extreme consequences, particularly if they involve dangerous goods, as demonstrated by the Lac-Mégantic occurrence. For this reason, the Board recommended that

the Department of Transport require Canadian railways to put in place additional physical defences to prevent runaway equipment.

Transportation Safety Recommendation R14-04

1.18.1 Actions by Transport Canada and industry following TSB Recommendation R14-04

On 29 October 2014, TC issued its emergency directive on additional physical defences for trains with operating locomotives that are left on the main track. It stated the following:

4a) Ensure that when equipment or movement are [sic] left unattended on main track, in addition to any securement requirements in Rule 112 of the CROR, at least one additional physical securement measure or mechanism is also used. The additional physical securement measures or mechanisms must prevent equipment from uncontrolled motion and must be one or more of the following:

- Permanent derails used within their design specifications;

- Mechanical emergency devices;

- Mechanical lock parking brake once approved by the Association of American Railroads (AAR);

- Reset Safety Control (RSC) with roll-away protection where air pressure is maintained or auto start is provided;

- Moving the equipment to a track protected with derails or bowled terrain verified by survey or track profile; or

- Other appropriate physical securement device accepted by Transport Canada.Footnote 36

TC also required railway companies to formulate rules to address the securement of railway equipment. Following extensive consultations with the industry, the newly revised CROR Rule 112 was approved by the Minister of Transport and came into effect on 15 October 2015.Footnote 37 Entitled "Leaving Unattended Equipment," the rule included 7 control measures that could be used as a secondary means of physical securement to reduce the risk of uncontrolled movements.

1.18.2 Board reassessment of Transport Canada's response to TSB Recommendation R14-04 (March 2018)

In March 2018, the Board reassessed TC's response to Recommendation R14-04 and acknowledged that TC has continued to monitor implementation of CROR Rule 112 and to monitor companies for compliance. However, in 2017, there were 62 occurrences involving uncontrolled movements, the second-highest annual total in the past 10 years. When the 10-year average (2008–2017) of 54.1 uncontrolled movements per year is compared with the most recent 5 years (2013–2017), the average number of uncontrolled movements per year has increased by 10% to 59.8. The reassessment indicated that

Uncontrolled movements continue to pose a risk to the rail transportation system. As the current defences do not seem sufficient to reduce the number of uncontrolled movements and improve safety, the Board considers the response to the recommendation as being Satisfactory In Part.

1.19 TSB Railway Investigation Report R16W0074 and safety concern

On 27 March 2016, at about 0235 Central Standard Time, while switching in Sutherland Yard in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, CP 2300RCLS training yard assignment was shoving a cut of cars into track F6. As the assignment was brought to a stop, empty covered hopper car EFCX 604991 uncoupled from the train, unnoticed by the crew. The car rolled uncontrolled through the yard and onto the main track within cautionary limits of the Sutherland Subdivision. The car travelled about 1 mile and over 2 public automated crossings before coming to a rest on its own. There were no injuries and there was no derailment. No dangerous goods were involved.

The investigation determined that, despite TC and industry initiatives, the desired outcome of significantly reducing the number of uncontrolled movements has not yet been achieved. Consequently, the Board was concerned that the current defences are not sufficient to reduce the number of uncontrolled movements and improve safety.

1.20 TSB occurrence statistics involving unplanned/uncontrolled movements

Before July 2014, the TSB Regulations defined a "reportable railway incident" as an incident resulting directly from the operation of rolling stock, in which "there is runaway rolling stock."Footnote 38 In July 2014, the TSB Regulations were revised, and this was changed to require reporting of any incident in which "there is an unplanned and uncontrolled movement of rolling stock."Footnote 39 While the criteria for reporting remained the same, the 2014 change was made to clarify what was meant by "runaway rolling stock."

From 2008 to 2017, there were 541 occurrences reported to the TSB related to unplanned and uncontrolled movements among all railways in Canada (Table 1).

| Reason for unplanned or uncontrolled movement | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of control | 6 | 0 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 21 |

| Switching without air | 17 | 14 | 10 | 16 | 12 | 24 | 21 | 22 | 18 | 21 | 175 |

| Securement | 25 | 37 | 25 | 32 | 43 | 42 | 38 | 35 | 29 | 39 | 345 |

| Total | 48 | 51 | 37 | 51 | 55 | 69 | 59 | 58 | 51 | 62 | 541 |

Uncontrolled movements generally fall into 1 of 3 causal categories:

- Loss of control: When a car, a cut of cars, or a train is left standing while attended, and available air brakes or locomotive systems cannot hold it or an LE or a Beltpack operator cannot control it using the available air brakes.

- Switching without air: When a movement is switching with the use of the locomotive independent brakes only (i.e., no air brakes are available on the cars being switched). When an uncontrolled movement occurs, this can result in the cars exiting a yard, siding, or customer track and entering the main track.

- Securement: When a car, a cut of cars, or a train is left unattended and begins to roll away uncontrolled, usually because

- no hand brake has been applied or insufficient hand brakes have been applied;

- a car (or cars) is equipped with faulty or ineffective hand brakes; and/or

- the train air brakes release for various reasons.

Table 2 provides a breakdown of the occurrences by consequences.

| Consequence | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Derailment of 1 to 5 cars | 23 | 29 | 18 | 22 | 26 | 26 | 28 | 28 | 27 | 28 | 255 |

| Derailment of more than 5 cars | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 14 |

| Collision | 24 | 30 | 24 | 32 | 28 | 40 | 35 | 32 | 23 | 34 | 302 |

| Affected the main track* | 9 | 4 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 61 |

| Involving dangerous goods | 16 | 12 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 14 | 17 | 14 | 9 | 18 | 125 |

| Injuries or fatalities | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 49 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 55 |

* Originated on the main track, moved onto the main track, or fouled the main track.

Of the 541 occurrences, the primary factor was loss of control, as in this occurrence, in 21 (4%); switching without air in 175 (32%); and insufficient securement in 345 (64%). As well, there were 302 unplanned/uncontrolled movements (56%) that resulted in a collision, and 61 (11%) that affected the main track. Of the 21 unplanned/uncontrolled movements that involved loss of control, as in this occurrence, 14 of them affected the main track.

Since 1994, in addition to this occurrence, the TSB has investigated 29 other occurrences that involved uncontrolled movements (Appendix F). The most significant of these occurrences was the 2013 Lac-Mégantic accident.

2.0 Analysis

No equipment or track defects were considered contributory to this occurrence. The analysis will focus on the actions of the crew that led to the uncontrolled movement, the effect of track gradient and train weight when operating without operative freight car air brakes, job briefings and job aids, employee operational experience on the west industrial yard assignment, regulatory oversight of training and qualifications, and statistics on uncontrolled movements.

2.1 The incident

At the south end of MacMillan Yard, the south crest of the bowl is on top of the Halton Subdivision railway overpass, about 1644 feet west of Signal 242D. There is a 0.35% ascending grade for trains approaching the south crest from the north. Once trains have passed over the crest, there is an eastward 0.70% descending grade approaching Signal 242D and extending east onto the York Subdivision. In this incident, the assignment had just accessed the York Subdivision main track when it began to roll uncontrolled eastward, ultimately rolling for about 3 miles.

The CN remote control locomotive system (RCLS) 2100 west industrial yard assignment crew had planned to pull all 74 cars at once. This required the assignment to gain access to the York Subdivision main track and move southward a distance of approximately 20 car lengths in order to clear the switch at the south end of the Halton outbound track before reversing to access track W100. The crew had not supplied air to the head-end cars, leaving only the locomotive independent brakes to control the assignment as it accessed the main track.

2.1.1 Effect of track gradient and weight of the assignment

The assignment consisted of 2 head-end locomotives, 72 loaded cars, and 2 empty cars. The 2 empty cars were in the head-end third of the train, located 17 and 19 car lengths from the head end, respectively. The assignment was 4537 feet long and weighed 9116 tons. Apart from the 2 empty cars, the assignment's weight was relatively equally distributed throughout the length of the assignment.

The assignment was assembled and began pulling the 74 cars southward from the yard onto the York 3 yard track. The assignment helper was located on the locomotive platform and controlled the assignment using a Beltpack, while the foreman was positioned on the ground at the track W100 switch. The assignment initially had difficulty moving and could reach a speed of only about 4 mph while pulling southward because of the weight of the assignment and the 0.35% ascending grade approaching the south crest.

When the assignment stopped at Signal 242D, the 24th car behind the locomotives was located on the south crest, 1644 feet west of the signal. About 36% of the assignment length and weight was located on the 0.70% descending eastward grade, and about 64% of the length and weight remained on the 0.35% northward descending grade. Consequently, the assignment could come to a controlled stop at Signal 242D using only the available locomotive independent brakes.

The assignment waited at Signal 242D for a permissive signal indication that would allow it to access the York Subdivision main track to move eastward, so that it could clear the switch at the south end of the Halton outbound track, then shove back to access the track W100 switch. At 2359:22, the helper received the expected permissive signal indication and began to pull the assignment eastward while the foreman communicated the distance required to clear the switch over the radio. After accessing the main track, the assignment reached a speed of about 8 mph. To prepare to stop the assignment at the request of the foreman, the helper applied the locomotive independent brakes, but the assignment continued to accelerate.