ISSN 2561-2247

The original version was signed by

Kathleen Fox

Chair

Transportation Safety Board of Canada

The original version was signed by

The Honourable Dominic LeBlanc

Minister of Intergovernmental and Northern

Affairs and Internal Trade, and President of

the Queen’s Privy Council for Canada

Chair's message

The past year has been a very productive one for the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB), with achievements in a number of different areas.

For instance, a core element of our mandate is to conduct independent investigations of selected transportation occurrences, and in 2017–18 we started and completed significantly more investigations than the previous year. Not only that, but we also reduced the overall average time each one took to complete, and almost completely eliminated the existing backlog of investigations.

Once that more technical side of our work was completed, we made sure people knew about our findings and recommendations, both the Canadian public as well as those in government and industry who are best-placed to take action and improve transportation safety. To that end, not only did we issue dozens of deployment notices, news releases, and media advisories, but we also fielded hundreds of media inquiries and set up numerous interviews with TSB investigators and senior officials—in addition to producing press conferences and YouTube videos, constantly updating our website, and sharing tweets and occurrence photos on social media.

Internally, we worked hard to streamline some of our organizational processes and fine-tune our approach to project management. This led to increased efficiency and better use of resources, and should help us to be more nimble in the future as we respond to an ever-changing environment.

Externally, we were pleased to note the recent passage of Bill C-49, which will require the mandatory installation of voice and video recorders in lead locomotives operating on main track. The Bill also contains amendments to the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act that will remove the legal barrier preventing companies from using on-board recorders for proactive safety management purposes. These changes have long been sought by the TSB and will help us advance safety going forward.

Finally, as a result of safety actions taken by “change agents”, we were able to close a total of 28 safety recommendations this year, almost all of them having received our highest rating of “Fully Satisfactory”. This puts the overall success rate at almost 80 percent — which is no small accomplishment when you consider that we’ve issued about 600 of these since the TSB was first created in 1990. There’s still room for improvement, however, and that’s exactly what we’ll keep doing as we strive to make Canada’s transportation system—already one of the world’s best—even safer.

Kathleen Fox

Results at a glance

2017-18 Transportation Safety Board of Canada

Resource Utilization

Financial: $32,409,284

Human: 214 full-time equivalents

- The accident rate and the number of fatalities continued to decrease in the Air, Marine and Pipeline sectors.

- In 2017-18, the TSB launched investigations for 54 of the reported occurrences. During the year, 66 investigations were completed, compared with 44 in the previous year. The number of investigations in progress at the end of the fiscal year decreased to 62 from 71 at the start. The backlog of old investigations was almost entirely eliminated.

- The average time to complete an investigation was 503 days, compared to 569 days in 2016-17 and the five-year average of 527 days. The reduction in average time over the past year is due to the TSB’s efforts to streamline processes and fine-tune its project management approach.

- A total of 63 safety recommendations were reassessed during 2017-18 with the result that the Board closed 28 of them, including 26 as Fully Satisfactory. This brings the TSB to an overall total of 79.6% of its recommendations assessed as Fully Satisfactory - a 3.3 percentage point increase compared to March 2017.

- The Media relations team issued 67 news releases and 16 media advisories, an increase of 26% over the previous year.

- During the year, TSB officials appeared before five Parliamentary committees on various matters related to transportation safety.

For more information on the TSB’s plans, priorities and results achieved, see the “Results: what we achieved” section of this report.

Raison d'être, mandate and role: who we are and what we do

Raison d'être

The Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board, referred to as the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) in its day-to-day activities, is an independent agency created in 1990 by an Act of Parliament. It operates at arm’s length from other government departments and agencies to ensure that there are no real or perceived conflicts of interest. The TSB’s sole objective is to advance air, marine, rail and pipeline transportation safety.

The President of the Queen’s Privy Council for Canada (who also serves as Minister of Intergovernmental and Northern Affairs and Internal Trade) is the designated minister for the purposes of tabling the TSB’s administrative reports in Parliament, such as the Departmental Plan and the Departmental Results Report. The TSB is part of the Privy Council portfolio of departments and agencies.

Mandate and role

The TSB performs a key role within the Canadian transportation system. We provide Canadians with an organization entrusted to advance transportation safety by:

- conducting independent investigations, including, when necessary, public inquiries, into selected transportation occurrences in order to make findings as to their causes and contributing factors;

- identifying safety deficiencies as evidenced by transportation occurrences;

- making recommendations designed to reduce or eliminate any such safety deficiencies;

- reporting publicly on our investigations and related findings; and

- following-up with stakeholders to ensure that safety actions are taken to reduce risks and improve safety.

The TSB may also represent Canadian interests in foreign investigations of transportation accidents involving Canadian citizens or Canadian registered, licensed or manufactured aircraft, ships or railway rolling stock. In addition, the TSB carries out some of Canada's obligations related to transportation safety at the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the International Maritime Organization (IMO).

As one of the world leaders in its field, the TSB regularly shares its investigation techniques, methodologies and tools with foreign safety organizations by inviting them to participate in in-house training programs in the areas of investigation methodology or human and organizational factors. Under the terms of international agreements, the TSB also provides investigation assistance to foreign safety organizations, such as downloading and analyzing flight recorder data or overseeing engine tear-downs. The TSB also shares data and reports with sister organizations, in addition to participating in international working groups and studies to advance transportation safety.

For more general information about the department, see the “Supplementary information” section of this report.

Operating context and key risks

Operating context

Operating context: conditions affecting our work

The TSB operates within the context of a very large and complex Canadian and international transportation system. Many Canadian and foreign organizations are responsible for, and involved in, improving transportation safety. The TSB does not have any power or authority to direct others to implement its recommendations or to make changes. The Board must therefore present its findings and recommendations in such a manner that compels others to act. This implies ongoing dialogue, information sharing and strategic coordination with many organizations such as Transport Canada, the National Energy Board and the Canadian Coast Guard. The TSB must also engage industry and foreign regulatory organizations in a similar fashion. Through various means, the TSB must present compelling arguments that will convince these “agents of change” to allocate resources and take action in response to identified safety deficiencies despite their many other competing priorities.

Furthermore, with the increasing globalization of the transportation industry, governments and industry are seeking greater harmonization of policies and practices between countries in order to facilitate cross-border trade, as well as the movement of people and goods. For example, rules that apply to trains crossing the Canada / U.S. border on a daily basis must be harmonized in order to avoid slowing or stopping their movements or creating administrative issues for the companies. This in turn makes the TSB’s work more difficult. In order to achieve results (i.e. get safety actions implemented), the TSB can no longer simply engage and convince Canadian stakeholders to act on their own. The TSB must convince both Canadian and foreign stakeholders to take actions in a coordinated and consistent manner.

The TSB's volume of activities is influenced by the number, severity and complexity of transportation occurrences, none of which can be effectively predicted. This uncertainty poses certain challenges with respect to the planning and management of TSB resources. Additionally, over the past few years the TSB’s visibility has increased significantly as a result of high-profile occurrence investigations, the TSB’s Outreach Program, and the increased use of social media to share safety information. The TSB’s enhanced visibility has generated higher stakeholder and public expectations than ever before.

In 2017-18, the TSB allocated a significant amount of resources to specific projects aimed at reviewing and modernizing its core business processes and its products so that the TSB is better positioned to continue fulfilling its mandate and to meet expectations in the years to come. For example, a new Policy on Occurrence Classification was created and will be implemented in fiscal year 2018-19. Efforts initiated in 2016-17, to eliminate the backlog of old investigations continued throughout the 2017-18 fiscal year while the management team ensured that a proper balance was maintained between the achievement of the short and long-term objectives.

Key risks: things that could affect our ability to achieve our plans and results

The TSB faces key strategic risks that represent a potential threat to the achievement of our mandate. These risks warrant particular vigilance from all levels of the organization.

A significant risk is managing workload and expectations. The TSB cannot predict the volume of activities since these are influenced by the number, severity and complexity of transportation occurrences. The public’s expectation is that the TSB will deploy and investigate all serious occurrences, will deliver timely answers on each investigation, and will make a difference in preventing future occurrences. This has resulted in higher expectations relating to the timeliness of TSB’s safety products, the quality of its work, and the number of safety products completed.

In a business environment where available resources are not expected to increase, the TSB must continue to meet its mandate within the existing limited budget. While there have been ongoing efforts to become more efficient in all areas of the organization, the constantly changing environment continues to create new demands and resource pressures. Furthermore, recently negotiated collective agreements for employees have resulted in significant cumulative increases in salary costs that could not be absorbed within the TSB’s budget. Discussions were therefore undertaken with central agencies to seek incremental funding for the short and long term.

Another risk faced by the TSB is challenges to its credibility. With the advent of social media, the public and media want factual information on what happened within minutes / hours, and they expect regular progress reports throughout the investigations. Key stakeholders also want timely information for their own use within their Safety Management System (SMS) or programs, and litigants want timely information to file early lawsuits. If the TSB does not ensure the review and modernization of its enabling legislation, core investigation processes, quality assurance / control processes, and make effective use of modern technologies, there is a risk that questions could be raised about the TSB’s processes, its continued relevance and its reputation.

The success of the TSB depends upon the expertise, professionalism and competence of its employees, so maintaining a qualified and healthy workforce remains a key risk. Challenges include recruiting and retaining experienced and qualified personnel in certain operational areas due to higher private sector salaries, a shortage of skilled workers for certain positions, and the on-going retirement of the baby-boomer cohort of employees. Another challenge is the need to be vigilant with respect to employee wellbeing. Due to the nature of the work performed by the TSB, employees may be exposed to significant work related stress. Occupational health and safety is also important, in particular because of the risks associated with deployments to occurrence sites involving exposure to many hazards. Without a skilled and healthy workforce, the TSB would not be able to deliver its mandate and achieve its key strategic objectives.

| Risks | Mitigating strategy and effectiveness | Link to the department's Core Responsibilities | Link to mandate letter commitments and any government‑wide or departmental priorities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Managing workload and expectations in a changing environment The TSB's ability to continue to effectively deliver its mandate and meet its obligations is at risk due to the unpredictable nature of occurrences, high public expectations, changing government priorities, limited financial resources, and other external changes beyond the TSB's control. |

The TSB will:

|

Independent safety investigations and communication of risks in the transportation system |

|

| Challenges to the TSB's credibility There is a risk that the TSB's operational effectiveness and credibility could be impacted if it fails to efficiently and effectively respond to requests for information and challenges to the TSB's legislation, business processes and methodologies. |

The TSB will:

|

Independent safety investigations and communication of risks in the transportation system |

|

| Maintaining a qualified and healthy workforce The TSB faces elevated risks in recruiting and retaining personnel due to specialized qualifications and the nature of its work. |

The TSB will:

|

Independent safety investigations and communication of risks in the transportation system |

|

Results: what we achieved

Core Responsibilities

Independent safety investigations and communication of risks in the transportation system

Description

The TSB’s sole objective is to advance air, marine, rail and pipeline transportation safety. The TSB has the following four key programs to support the core responsibility:

- Aviation Occurrence Investigations

- Marine Occurrence Investigations

- Rail Occurrence Investigations

- Pipeline Occurrence Investigations

All four occurrence investigations programs are governed by the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act and the Transportation Safety Board Regulations. The Aviation Occurrence Investigations program is also governed by Annex 13 of the Convention on International Civil Aviation, and the Marine Occurrence Investigations program is also governed by the Casualty Investigation Code of the International Maritime Organization.

Under the Aviation, Marine, Rail and Pipeline programs, the TSB conducts independent investigations into selected transportation occurrences in, or over Canada, to identify causes and contributing factors. These programs include the publication of investigation reports, the formulation and monitoring of recommendations and other safety communications, as well as the conduct of outreach activities to advocate for changes to operating practices, equipment, infrastructure, and regulations to advance transportation safety.

The Aviation Occurrence Investigations program may also conduct investigations internationally, and includes the fulfillment of specific Government of Canada obligations related to transportation safety under conventions of the International Civil Aviation Organization and other international agreements.

The Marine Occurrence Investigations program may also conduct investigations internationally, and includes the fulfillment of specific Government of Canada obligations related to transportation safety under conventions of the International Maritime Organization and other international agreements.

The Rail Occurrence Investigations program also includes the provision of assistance, upon request, to the provinces for the investigation of short-line railway occurrences under provincial jurisdiction.

Planning highlights

The achievement of the TSB’s mandate is measured through three sets of departmental performance indicators. First, some performance indicators are aimed at reporting upon the overall safety of the transportation system. However, many variables influence transportation safety and many organizations play a role in this ultimate outcome. There is no way to directly attribute overall safety improvements to any specific organization. Accident and fatality rates are used as the best available indicators. In recent years, these indicators have reflected positive advancements in transportation safety and positive results are expected again in 2018-19.

Secondly, the TSB’s departmental results are also measured through actions taken by its stakeholders in response to its safety communications. Finally, results are also measured through efficiency indicators. The TSB must present compelling arguments that convince “change agents” to take actions in response to identified safety deficiencies. The responses received, the actions taken and their timeliness are good indicators of the TSB’s impact on transportation safety. The TSB actively engages with stakeholders in all modes. However, the established performance targets vary by mode to reflect the different base lines and the differing challenges from one mode to another.

Even though the average time to complete investigations was reduced in the past year, the TSB has not fully achieved all its targets for all performance indicators in all modes of transportation. A new Policy on Occurrence Classification was developed and will be implemented in fiscal year 2018-19. As many changes will be made to business processes and new products will be introduced, the TSB’s performance indicators and related targets will need to be reviewed and updated to properly measure results for each mode of transportation.

Serving Canadians

In 2017-18, the TSB completed the implementation of the new investigation management approach introduced in summer 2016. This new approach includes: a greater emphasis on team work, more rigorous project management, increased collaboration across organizational units, and refresher training for investigators on the investigation methodology and report writing. Efforts to catch-up on the backlog of older investigations were also completed. However, despite these efforts, the TSB did not fully meet its efficiency targets in 2017-18. However, real and measurable progress was achieved on a number of indicators.

Efforts were made to collaborate with Transport Canada to review all outstanding recommendations and take appropriate actions to close some older ones that have been outstanding for much too long. A particular focus was placed on aviation recommendations given the larger number of outstanding recommendations in that program. The TSB has also continued its outreach activities to engage stakeholders in proactive discussions and encourage them to initiate safety actions that can mitigate the risks identified. Work also continued on the implementation of the TSB’s Open Government Plan. Additional data elements from the modal occurrence databases were added to the datasets published on the TSB web site and the open data portal. Further enhancements continue to be made to the TSB web site and to the TSB presence on the Canada.ca site.

Improving core business process and products

Significant time and effort has been invested in 2017-18 to review and modernize the TSB’s investigation policies, processes and products. A number of working groups were used to engage employees and managers from across the TSB in this renewal exercise. A new Policy on Occurrence Classification has been finalized for publication in early 2018-19. The implementation of changes in the way the TSB conducts its investigations and reports on them has started and will continue progressively over the coming year. New products, such as short form reports, will also be introduced in order to better respond to the needs of our stakeholders and the public.

New processes for program evaluation and lessons learned were also developed and will be put in place to support continuous improvement and help the TSB become a learning organization.

Updating legislative and regulatory frameworks

One of the long standing safety issues in the rail mode is the implementation of locomotive voice and video recorders (LVVR). These recorders could provide very valuable information to assist TSB investigators in their work. These recorders could also help the railways proactively manage safety if used properly. In response to the TSB call for action, the Minister of Transport had identified this issue as a key priority for 2017-18 and Bill C-49 was tabled in Parliament in May 2017. This new legislation made its way through Parliament and received Royal Assent in May 2018. The TSB will now shift its focus on working in close collaboration with Transport Canada to develop appropriate regulatory proposals to implement the provisions of the new legislation.

During 2017-18, the TSB has made small modifications to its regulations in order to clarify certain sections in light of stakeholder feedback. These regulatory changes were published in the Canada Gazette, Part I for formal consultation.

Results

| Departmental Results | Departmental Indicators | Target | Date to achieve target | 2017–18 Actual results | 2016–17 Actual results | 2015–16 Actual results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation system is safer | Accident rate (over 10-year period) | Continue downward trend in accident rateFootnote 1 | 31 March 2018 | Aviation = Met: There has been a significant downward trend in the accident rate for Canadian-registered aircraft over the past 10 years. The aviation accident rate in 2017 was 4.3 accidents per 100,000 hours flown, below the 10-year average of 4.8. |

Aviation = Met: There has been a significant downward trend in the accident rate for Canadian-registered aircraft over the past 10 years. The aviation accident rate in 2016 was 4.5 accidents per 100,000 hours flown, below the 10-year average of 5.7. |

Aviation = Met: There has been a significant downward trend in the accident rate for Canadian-registered aircraft over the past 10 years. The aviation accident rate in 2015 was 5.1 accidents per 100,000 hours flown, below the 10-year average of 5.8. |

| Marine = Met: 2017 accident rates for Canadian flag commercial vessels, for foreign commercial non-fishing vessels, and for fishing vessels was lower than the 10-year averages. The marine accident rates in 2017 were: 2.5 accidents per 1,000 vessel movements for Canadian flag commercial vessels, below the 10-year average of 3.1. 1.3 accidents per 1,000 vessel movements for foreign commercial non-fishing vessels, below the 10-year average of 1.5. 5.8 accidents per 1,000 active fishing vessels, below the 10-year average of 6.7. |

Marine = Met: 2016 accident rates for Canadian flag commercial vessels, for foreign commercial non-fishing vessels, and for fishing vessels was lower than the 10-year averages. The marine accident rates in 2016 were: 2.7 accidents per 1,000 vessel movements for Canadian flag commercial vessels, below the 10-year average of 3.0. 1.0 accident per 1,000 vessel movements for foreign commercial non-fishing vessels, below the 10-year average of 1.5. 6.2 accidents per 1,000 active fishing vessels, below the 10-year average of 6.7. |

Marine = Met: 2015 accident rates for Canadian flag commercial vessels, for foreign commercial non-fishing vessels, and for fishing vessels was lower than the 10-year averages.Footnote 2 | ||||

| Rail = Not met: The main-track accident rate in 2017 was 2.6 accidents per million main-track train miles, above the 10-year average of 2.4. | Rail = Not met: The main-track accident rate in 2016 was 2.8 accidents per million main-track train miles, up from the 10-year average of 2.5. | Rail = Not met: The main-track accident rate in 2015 was 3.0 accidents per million main-track train miles, up from the 10-year average of 2.5. | ||||

| Pipeline = Met: The 2017 rate was 0.3 pipeline accidents per exajoule, below the 10-year average of 0.5. | Pipeline = Met: The 2016 rate was 0 pipeline accidents per exajoule, below the 10-year average of 0.6. | Pipeline = Met: The 2015 rate was 0 pipeline accidents per exajoule, down from the 10-year average of 0.6. | ||||

| Number of fatal accidents (over 10-year period) | Reduction in number of fatal accidentsFootnote 3 | 31 March 2018 | Aviation = Met: The number of fatal accidents was 21, below the 10-year average of 33.4 and fatalities in 2017 totaled 32, lower than the 10-year average of 57. | Aviation = Met: The number of fatal accidents was 29, below the 10-year average of 33.9 and fatalities in 2016 totaled 45, lower than the 10-year average of 58. | Aviation = Met: The number of fatal accidents and fatalities in 2015 was 29, below the 10-year average of 35.4 and fatalities in 2015 totaled 47, lower than the 10-year average of 60. | |

| Marine = Met: The number of fatal accidents was 10, below the 10-year average of 12.4 and the number of fatalities in 2017 totaled 11, lower than the 10-year average of 16.4. | Marine = Met: The number of fatal accidents was 4, below the 10-year average of 13.7 and the number of fatalities in 2016 totaled 7, lower than the 10-year average of 17.5. | Marine = Met: The number of fatal accidents was lower than the 10-year average. However, the number of fatalities in 2015 was up slightly from the 10-year average. | ||||

| Rail = Not met: The number of fatal accidents in 2017 was 75, above the 10-year average of 67. Rail fatalities totaled 77 in 2017, above the 10-year average of 76. |

Rail = Met: The number of fatal accidents in 2016 was 62, below the 10-year average of 70. Rail fatalities totaled 66 in 2016, lower than the 10-year average of 78. |

Rail = Met: The number of fatal accidents in 2015 was 46, down from the 10-year average of 75. Rail fatalities totaled 46 in 2015, down from the 10-year average of 84. |

||||

| Pipeline = Met: There have been no fatal accidents. | Pipeline = Met: There have been no fatal accidents. | Pipeline = Met: There have been no fatal accidents. | ||||

| The regulators and the transportation industry respond to identified safety deficiencies | Percentage of responses to recommendations assessed as Fully SatisfactoryFootnote 4 | Aviation= 64% | 31 March 2018 | Aviation = Met: 73% | Aviation= Not Met: 64% | Aviation = Met: 67% |

| Marine = 85% | Marine = Met: 86% |

Marine = Not met: 84% | Marine = Met: 87% | |||

| Rail = 89% | Rail = Not met: 88% | Rail = Met: 88% | Rail = Met: 88% | |||

| Pipeline= 100% | Pipeline = Met: 100% | Pipeline = Met: 100% | Pipeline = Met: 100% | |||

| Percentage of safety advisories on which safety actions have been taken | Aviation= 60% | 31 March 2018 | Aviation = Met: 100% | Aviation= Met: 100% | Aviation= Met: 100% | |

| Marine= 60% | Marine = Not met: 0% | Marine = Not met: 33% | Marine = Met: 60% | |||

| Rail = 75% | Rail = Not met: 29% | Rail = Not met: 50% | Rail = Met: 75% | |||

| Pipeline= 75% | Pipeline = Not ApplicableFootnote 4a | Pipeline = Not ApplicableFootnote 5 | Pipeline= Not ApplicableFootnote 4b | |||

| Average time recommendations have been outstanding (active and dormant recommendations) | 7 years | 31 March 2018 | Aviation = Not met: 12.4 years | Aviation = Not met: 14.2 years | Aviation = Not met: 15.1 years | |

| Marine = Not met: 10.9 years | Marine = Not met: 12.5 years | Marine = Not met: 14.8 years | ||||

| Rail = Met: 6.5 years |

Rail = Met: 6.3 years | Rail = Not met: 7.4 years | ||||

| Pipeline = Not Applicable | Pipeline = Not Applicable | Pipeline = Not Applicable | ||||

| Occurrence investigations are efficient | Average time for completing investigation reports | 450 days | 31 March 2018 | Aviation = Not met: 545 days | Aviation Not met: 656 days | Aviation = Not met: 548 days |

| Marine = Not met: 466 days | Marine = Exceeded: 438 days | Marine = Exceeded: 406 days | ||||

| Rail = Not met: 481 days | Rail = Not met: 519 days | Rail = Not met: 525 days | ||||

| Pipeline = Exceeded: 275 days | Pipeline = Not Applicable | Pipeline = Not met: 650 days | ||||

| Percentage of investigations completed within the published targettime | 75% | 31 March 2018 | Aviation = Not met: 28% | Aviation = Not met: 15% | Aviation = Not met: 21% | |

| Marine = Not met: 50% | Marine = Not met: 43% | Marine = Not met: 73% | ||||

| Rail = Not met: 40% | Rail = Not met: 29% | Rail = Not met: 25% | ||||

| Pipeline = Met: 100% | Pipeline = Not Applicable | Pipeline = Not met: 0% |

| 2017–18 Main Estimates |

2017–18 Planned spending |

2017–18 Total authorities available for use |

2017–18 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2017–18 Difference (Actual spending minus Planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23,827,409 | 24,377,678 | 27,332,657 | 26,156,576 | 1,176,081 |

| 2017–18 Planned full-time equivalents | 2017–18 Actual full-time equivalents | 2017–18 Difference (Actual full-time equivalents minus Planned full-time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 169 | 169 | 0 |

Financial, human resources and performance information for the TSB's Program Inventory is available in the GC InfoBase.Footnote i

Internal Services

Description

Internal Services are those groups of related activities and resources that the federal government considers to be services in support of programs and/or required to meet corporate obligations of an organization. Internal Services refers to the activities and resources of the 10 distinct service categories that support Program delivery in the organization, regardless of the Internal Services delivery model in a department. The 10 service categories are: Management and Oversight Services; Communications Services; Legal Services; Human Resources Management Services; Financial Management Services; Information Management Services; Information Technology Services; Real Property Services; Materiel Services; and Acquisition Services.

Results

Despite some challenges in 2017-18, the Internal Services program continued to deliver on-going services in support of the four investigation programs and corporate obligations. Work continued on implementation of the Open Government initiative and additional data elements were added to datasets available on the web. Continuous improvement measures were implemented with respect to Information Management. Work with Library and Archives Canada to finalize the review and update of retention and disposal schedules for TSB records of enduring business value is almost completed. The Electronic Occurrence Notification Systems (EONS) and updated Pipeline occurrence database were successfully deployed in Fall 2017.

The Finance Division continued to work in collaboration with the HR Division and PSPC compensation personnel to ensure that Phoenix issues were minimized and employees were paid in a timely manner. Where appropriate, cash advances were issued to employees. Work started on the implementation of the new Employment Equity Plan. A new Telework Policy was implemented to provide employees with more flexibility. A series of awareness workshops on mental health in the workplace were offered to employees.

Progress was made on the strategy to co-locate the TSB’s Head Office and Engineering Lab in a modern facility within the National Capital Region through participation in the Federal Science and Technology Infrastructure Initiative. Our Quebec office moved to new modern offices.

The utilization of human resources for Internal Services was lower than planned due to vacancies in some positions.

| 2017–18 Main Estimates |

2017–18 Planned spending |

2017–18 Total authorities available for use |

017–18 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2017–18 Difference (Actual spending minus Planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5,589,145 | 5,718,221 | 6,533,849 | 6,252,708 | 281,141 |

| 2017–18 Planned full-time equivalents | 2017–18 Actual full-time equivalents | 2017–18 Difference (Actual full-time equivalents minus Planned full-time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 51 | 45 | (6) |

Analysis of trends in spending and human resources

Actual expenditures

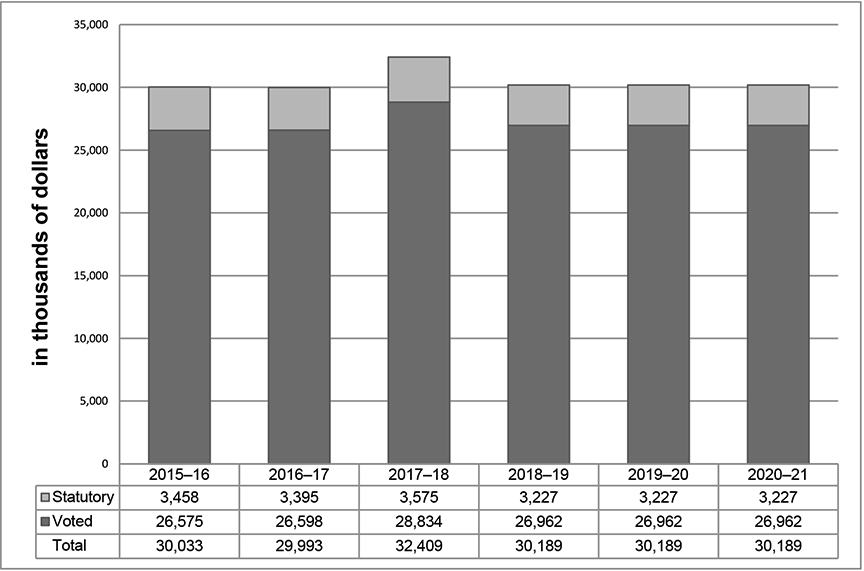

Departmental spending trend graph

Departmental spending trend graph - Details

| 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statutory | 3,458 | 3,395 | 3,575 | 3,227 | 3,227 | 3,227 |

| Voted | 26,575 | 26,598 | 26,834 | 26,962 | 26,962 | 28,962 |

| Total | 30,033 | 29,993 | 32,409 | 30,189 | 30,189 | 30,189 |

| Core Responsibilities and Internal Services | 2017–18 Main Estimates |

2017–18 Planned spending |

2018–19 Planned spending |

2019–20 Planned spending |

2017–18 Total authorities available for use | 2017–18 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2016–17 Actual spending (authorities used) | 2015–16 Actual spending (authorities used) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent safety investigations and communication of risks in the transportation system | 23,827,409 | 24,377,678 | 24,151,162 | 24,151,162 | 27,332,657 | 26,156,576 | 23,989,597 | 24,360,425 |

| Internal Services | 5,589,145 | 5,718,221 | 6,037,790 | 6,037,790 | 6,533,849 | 6,252,708 | 6,003,148 | 5,672,065 |

| Total | 29,416,554 | 30,095,899 | 30,188,952 | 30,188,952 | 33,866,506 | 32,409,284 | 29,992,745 | 30,032,490 |

The 2015-16 to 2017-18 actual spending results presented are actual amounts as published in the Public Accounts of Canada. Actual spending in fiscal years 2015-16 and 2016-17 was lower than 2017-18 as the TSB had actively reduced its expenditures in the first two years in order to establish a reserve fund to pay for retro-active salary expenditures in 2017-18. The increase in salary spending in 2017-18 is due to the implementation of newly signed collective agreements, which resulted not only in increases to employees’ current year salaries but also payments for employees’ retroactive salary increases from previous years. The TSB received additional funding in Supplementary Estimates B in the amount of $1.8 million to assist with this funding pressure. However, the additional funding was not fully utilized because a number of positions were vacant for a portion of the year thereby freeing-up some funds.

Although most impacts resulting from the signed collective agreements were resolved in 2017-18, there are still two collective agreements that remain unsigned at the end of 2017-18. The TSB will need to pay the associated retroactive salary costs, as well as the retroactive salary increases for Executives and Governor-in-Council appointees, in future years. Additional future liabilities for the TSB exist in the form of deferred compensatory leave and vacation payouts for the past two years which are anticipated to be paid out in 2019-20. The TSB is implementing contingency measures in order to cover these future costs.

In accordance with the definition of planned spending, amounts for 2018-19 and ongoing fiscal years consists of Main Estimates amounts only. The TSB's authorities increased by $0.8 million compared to the previous year's Main Estimates. This increase in funding is primarily attributable to collective bargaining adjustments and the associated amounts for Employee Benefit Plans.

Actual human resources

| Core Responsibilities and Internal Services | 2015–16 Actual full-time equivalents | 2016–17 Actual full-timeequivalents | 2017–18 Planned full-time equivalents |

2017–18 Actual full-time equivalents | 2018–19 Planned full-time equivalents | 2019–20 Planned full-time equivalents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent safety investigations and communication of risks in the transportation system | 164 | 168 | 169 | 169 | 170 | 170 |

| Internal Services | 45 | 46 | 51 | 45 | 50 | 50 |

| Total | 209 | 214 | 220 | 214 | 220 | 220 |

Actual and forecast full-time equivalents for 2017-18 and prior years are less than the anticipated 220 due to vacant positions. Planned figures for 2018-19 and onward show a stable workforce.

Expenditures by vote

For information on the TSB's organizational voted and statutory expenditures, consult the Public Accounts of Canada 2017–2018.Footnote ii

Government of Canada spending and activities

Information on the alignment of the TSB’s spending with the Government of Canada’s spending and activities is available in theGC InfoBase.Footnote ia

Financial statements and financial statements highlights

Financial statements

The TSB's financial statements (unaudited) for the year ended March 31, 2018 are available on the departmental website.

Financial statements highlights

| Financial information | 2017–18 Planned results |

2017–18 Actual results |

2016–17 Actual results |

Difference (2017–18 Actual results minus 2017–18 Planned results) | Difference (2017–18 Actual results minus 2016–17 Actual results) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total expenses | 35,398 | 35,782 | 35,375 | 384 | 407 |

| Total revenues | 35 | 120 | 73 | 85 | 47 |

| Net cost of operations before government funding and transfers | 35,363 | 35,662 | 35,302 | 299 | 360 |

The 2017–18 Planned Results are based on estimates known at the time of the Departmental Plan. The difference between total expenses for 2017–18 Planned Results and 2017–18 Actual is mainly due to events not known during the Departmental Plan preparation phase. Planned expenses for 2017-18 were estimated at $35.4 million while actual expenses are slightly higher at $35.8 million.

On an accrual accounting basis, TSB total operating expenses for 2017-18 are $35.8 million, a slight increase of $0.4 million (1.1%) when compared to the previous fiscal year. There was no significant variance in any of the categories of expenses.

The TSB’s revenues are incidental and result from cost recovery activities from training or investigation activities, proceeds from the disposal of surplus assets, and fees generated by requests under the Access to Information Act.

| Financial Information | 2017–18 | 2016–17 | Difference (2017–18 minus 2016–17) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total net liabilities | 5,970 | 6,015 | (45) |

| Total net financial assets | 3,091 | 2,226 | 865 |

| Departmental net debt | 2,879 | 3,789 | (910) |

| Total non‑financial assets | 4,771 | 4,966 | (195) |

| Departmental net financial position | 1,892 | 1,177 | 715 |

The TSB’s total net liabilities consist primarily of accounts payable and accrued liabilities relating to operations which account for $3.4 million and 56% (57% in 2016-17) of total liabilities. The liability for employee future benefits pertaining to severance pay represents $1.1 million and 18% (18% in 2016-17) of total liabilities, while the liability for vacation pay and compensatory leave accumulated by employees but not taken at year-end represents $1.5 million and 26% (25% in 2016-17). As a result, the TSB’s total net liabilities are consistent to previous year’s balances.

Total net financial assets consist of accounts receivable, advances, and amounts due from the Consolidated Revenue Fund (CRF) of the Government of Canada. The amount due from the CRF represents 89% or $2.8 million (86% in 2016-17) of the year-end balance, an increase of $0.8 million. This represents an increase in the amount of net cash that the TSB is entitled to draw from the CRF in the future to discharge its current liabilities without further appropriations. The TSB’s total net financial assets have increased by $0.9 million between years resulting from the higher amount due from the CRF.

Total non-financial assets consist primarily of tangible capital assets, which make up $4.6 million or 97% of the balance (97% in 2016-17), with inventory and prepaid expenses accounting for the remainder. The decrease of $0.2M in non-financial assets between years is due to the annual amortization of assets ($0.9 million) which is offset in part by the acquisition of new assets ($0.7 million).

Supplementary information

Corporate information

Organizational profile

Appropriate minister: The Honourable Dominic LeBlanc

Institutional head: Kathleen Fox

Ministerial portfolio: Privy Council

Enabling instrument[s]: Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act,Footnote iii S.C. 1989, c. 3

Year of incorporation / commencement: 1990

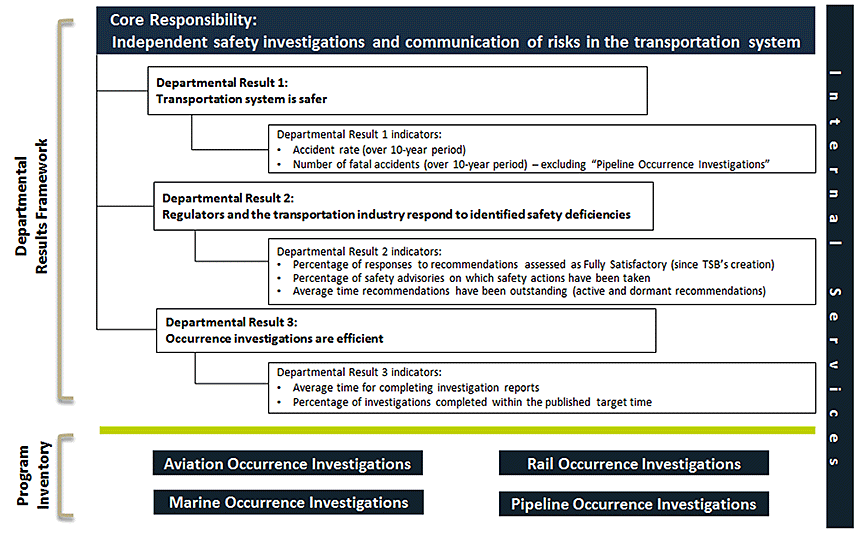

Reporting framework

The TSB Departmental Results Framework and Program Inventory of record for 2017–18 are shown on the next page.

| 2017–18 Core Responsibilities and Program Inventory | 2016–17 Lowest-level program of the Program Alignment Architecture | Percentage of lowest-level Program Alignment Architecture program (dollars) corresponding to the Program in the Program Inventory |

|---|---|---|

| Independent safety investigations and communication of risks in the transportation system | Independent investigations into transportation occurrences contribute to making the transportation system safer | |

| Aviation Occurrence Investigations | Aviation Occurrence Investigations | 100 |

| Marine Occurrence Investigations | Marine Occurrence Investigations | 100 |

| Rail Occurrence Investigations | Rail Occurrence Investigations | 100 |

| Pipeline Occurrence Investigations | Pipeline Occurrence Investigations | 100 |

| Internal Services | Internal Services | 100 |

Supporting information on the Program Inventory

Financial, human resources and performance information for the TSB's Program Inventory is available in the GC InfoBase.Footnote ib

Supplementary information tables

The following supplementary information tables are available on the TSB's website:Footnote iv

Organizational contact information

Additional information about the Transportation Safety Board of Canada and its activities is available on the TSB websiteFootnote v or by contacting us at:

Transportation Safety Board of Canada

Place du Centre

200 Promenade du Portage, 4th Floor

Gatineau, Quebec K1A 1K8

E-mail: communications@tsb.gc.ca

Social media: socialmedia-mediassociaux@tsb.gc.ca

Toll Free: 1-800-387-3557

Appendix: Definitions

- appropriation (crédit)

- Any authority of Parliament to pay money out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund.

- budgetary expenditures (dépenses budgétaires)

- Operating and capital expenditures; transfer payments to other levels of government, organizations or individuals; and payments to Crown corporations.

- Core Responsibility (responsabilité essentielle)

- An enduring function or role performed by a department. The intentions of the department with respect to a Core Responsibility are reflected in one or more related Departmental Results that the department seeks to contribute to or influence.

- Departmental Plan (Plan ministériel)

- A report on the plans and expected performance of an appropriated department over a three year period. Departmental Plans are tabled in Parliament each spring.

- Departmental Result (résultat ministériel)

- A Departmental Result represents the change or changes that the department seeks to influence. A Departmental Result is often outside departments’ immediate control, but it should be influenced by program-level outcomes.

- Departmental Result Indicator (indicateur de résultat ministériel)

- A factor or variable that provides a valid and reliable means to measure or describe progress on a Departmental Result.

- Departmental Results Framework (cadre ministériel des résultats)

- Consists of the department’s Core Responsibilities, Departmental Results and Departmental Result Indicators

- Departmental Results Report (Rapport sur les résultats ministériels)

- A report on an appropriated department’s actual accomplishments against the plans, priorities and expected results set out in the corresponding Departmental Plan.

- evaluation (évaluation)

- In the Government of Canada, the systematic and neutral collection and analysis of evidence to judge merit, worth or value. Evaluation informs decision making, improvements, innovation and accountability. Evaluations typically focus on programs, policies and priorities and examine questions related to relevance, effectiveness and efficiency. Depending on user needs, however, evaluations can also examine other units, themes and issues, including alternatives to existing interventions. Evaluations generally employ social science research methods.

- experimentation (expérimentation)

- Activities that seek to explore, test and compare the effects and impacts of policies, interventions and approaches, to inform evidence-based decision-making, by learning what works and what does not.

- full time equivalent (équivalent temps plein)

- A measure of the extent to which an employee represents a full person year charge against a departmental budget. Full time equivalents are calculated as a ratio of assigned hours of work to scheduled hours of work. Scheduled hours of work are set out in collective agreements.

- gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) (analyse comparative entre les sexes plus [ACS+])

- An analytical approach used to assess how diverse groups of women, men and gender-diverse people may experience policies, programs and initiatives. The “plus” in GBA+ acknowledges that the gender-based analysis goes beyond biological (sex) and socio-cultural (gender) differences. We all have multiple identity factors that intersect to make us who we are; GBA+ considers many other identity factors, such as race, ethnicity, religion, age, and mental or physical disability. Examples of GBA+ processes include using data disaggregated by sex, gender and other intersecting identity factors in performance analysis, and identifying any impacts of the program on diverse groups of people, with a view to adjusting these initiatives to make them more inclusive.

- government-wide priorities (priorités pangouvernementales)

- For the purpose of the 2017–18 Departmental Results Report, those high-level themes outlining the government’s agenda in the 2015 Speech from the Throne, namely: Growth for the Middle Class; Open and Transparent Government; A Clean Environment and a Strong Economy; Diversity is Canada’s Strength; and Security and Opportunity.

- horizontal initiatives (initiative horizontale)

- An initiative where two or more departments are given funding to pursue a shared outcome, often linked to a government priority.

- non budgetary expenditures (dépenses non budgétaires)

- Net outlays and receipts related to loans, investments and advances, which change the composition of the financial assets of the Government of Canada.

- performance (rendement)

- What an organization did with its resources to achieve its results, how well those results compare to what the organization intended to achieve, and how well lessons learned have been identified.

- performance indicator (indicateur de rendement)

- A qualitative or quantitative means of measuring an output or outcome, with the intention of gauging the performance of an organization, program, policy or initiative respecting expected results.

- performance reporting (production de rapports sur le rendement)

- The process of communicating evidence based performance information. Performance reporting supports decision making, accountability and transparency.

- plan (plan)

- The articulation of strategic choices, which provides information on how an organization intends to achieve its priorities and associated results. Generally a plan will explain the logic behind the strategies chosen and tend to focus on actions that lead up to the expected result.

- planned spending (dépenses prévues)

- For Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports, planned spending refers to those amounts that receive Treasury Board approval by February 1. Therefore, planned spending may include amounts incremental to planned expenditures presented in the Main Estimates.

A department is expected to be aware of the authorities that it has sought and received. The determination of planned spending is a departmental responsibility, and departments must be able to defend the expenditure and accrual numbers presented in their Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports. - priority (priorité)

- A plan or project that an organization has chosen to focus and report on during the planning period. Priorities represent the things that are most important or what must be done first to support the achievement of the desired Strategic Outcome(s) or Departmental Results.

- Program (programme)

- Individual or groups of services, activities or combinations thereof that are managed together within the department and focus on a specific set of outputs, outcomes or service levels.

- Program Inventory (répertoire des programmes)

- Identifies all of the department’s programs and describes how resources are organized to contribute to the department’s Core Responsibilities and Results.

- result (résultat)

- An external consequence attributed, in part, to an organization, policy, program or initiative. Results are not within the control of a single organization, policy, program or initiative; instead they are within the area of the organization’s influence.

- statutory expenditures (dépenses législatives)

- Expenditures that Parliament has approved through legislation other than appropriation acts. The legislation sets out the purpose of the expenditures and the terms and conditions under which they may be made.

- sunset program (programme temporisé)

- A time limited program that does not have an ongoing funding and policy authority. When the program is set to expire, a decision must be made whether to continue the program. In the case of a renewal, the decision specifies the scope, funding level and duration.

- target (cible)

- A measurable performance or success level that an organization, program or initiative plans to achieve within a specified time period. Targets can be either quantitative or qualitative.

- voted expenditures (dépenses votées)

- Expenditures that Parliament approves annually through an Appropriation Act. The Vote wording becomes the governing conditions under which these expenditures may be made.