Stall and collision with terrain

Privately registered

Cessna 150G, C-FWGF

Saint-Rémi, Quebec

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

History of the flight

Toward the end of the afternoon on 21 April 2023, the student pilot and owner of the Cessna 150G aircraft (registration C-FWGF, serial number 15067098) and a friend arrived at the field of a private farm in Saint-Urbain-Premier, Quebec, where the aircraft had been parked. At 1753,Footnote 1 the student pilot sent a text message to his flight instructor to inform him that he was going to fly. The instructor, who was in Saint-Lazare, Quebec, authorized the solo flight.Footnote 2

The aircraft took off at approximately 1830 for a local flight, with the student pilot and his friend on board. Weather conditions were suitable for a day visual flight rules (VFR) flight, and winds were from the north-northwest at about 14 knots. At approximately 1920, the aircraft flew at low altitudeFootnote 3 over a residential area west of Saint-Rémi, Quebec, where about 15 people were attending an outdoor gathering on a private property. One of the individuals recognized the aircraft and called the student pilot at 1921 using a mobile application that allowed video calls, asking him to put on a “show.” The conversation lasted 21 seconds, and shortly afterwards, the aircraft approached the gathering from the north.

The aircraft began to fly in a steep nose-up attitude and then, after executing a manoeuvre that the investigation was unable to identify, ended up in a vertical descent. The aircraft then severed power lines before crashing onto the roof of an automobile parked in the driveway of a house approximately 100 feet from the gathering.

A fire broke out. Several people rushed over to help out the student pilot and passenger. Both were seriously injured and taken to hospital by ambulance. The fire spread to the house and was brought under control by firefighters once they arrived at the scene. No one on the ground was injured. The aircraft was destroyed.

Student pilot information

The student pilot had a valid Category 4 medical certificate, issued by Transport Canada (TC) on 26 April 2022, and a student pilot permit issued on 24 June 2022.

The student pilot had begun flight training on 28 January 2022 on a Cessna 172 aircraft owned by Ikaros International Flight Training Inc. (IKAROS). He had acquired the occurrence aircraft on 16 June 2022 and then continued his flight training on this aircraft. According to his flight training record, he had conducted his first solo flight on 24 June 2022. At the time of the occurrence, his record showed 163.3 total flight hours, including 158.1 flown on the occurrence aircraft.

Instructor information

The flight instructor had a commercial pilot licence – aeroplane and a valid Category 1 medical certificate. Among his ratings was a Class 2 Flight Instructor rating valid until 01 July 2023, and he was IKAROS’s founder and chief flight instructor.

TC had issued a flight training unit operator certificate to IKAROS on 06 September 2013. TC suspended this operator certificate on 23 February 2023 at the request of IKAROS, which no longer met the certificate requirements because the school’s only aircraft was destroyed when the hangar it was stored in collapsed. From then on, the instructor continued to provide flight training as a freelance instructor.

Aircraft information

The occurrence aircraft was manufactured in 1967 by the Cessna Aircraft Company in Wichita, Kansas, United States, and designated as “Model 150G.” It was equipped with an emergency locator transmitter that could transmit only on 121.5 MHz and 243 MHz. No distress signal was reported after the collision.

The aircraft’s technical records could not be obtained, and it was impossible to establish the total air time hours, the date that maintenance had last been performed, or whether any deficiencies had been identified.

Accident site and examination of the wreckage

The intensity of the fire that broke out after the collision indicates that there was fuel on board. The middle section of the aircraft, including the cockpit, was completely destroyed by the fire. No deficiencies in flight control continuity were identified in the components that were undamaged by the fire.

An examination of the automobile revealed substantial scoring marks on the roof and right front fender, consistent with damage typically caused by propeller rotation.

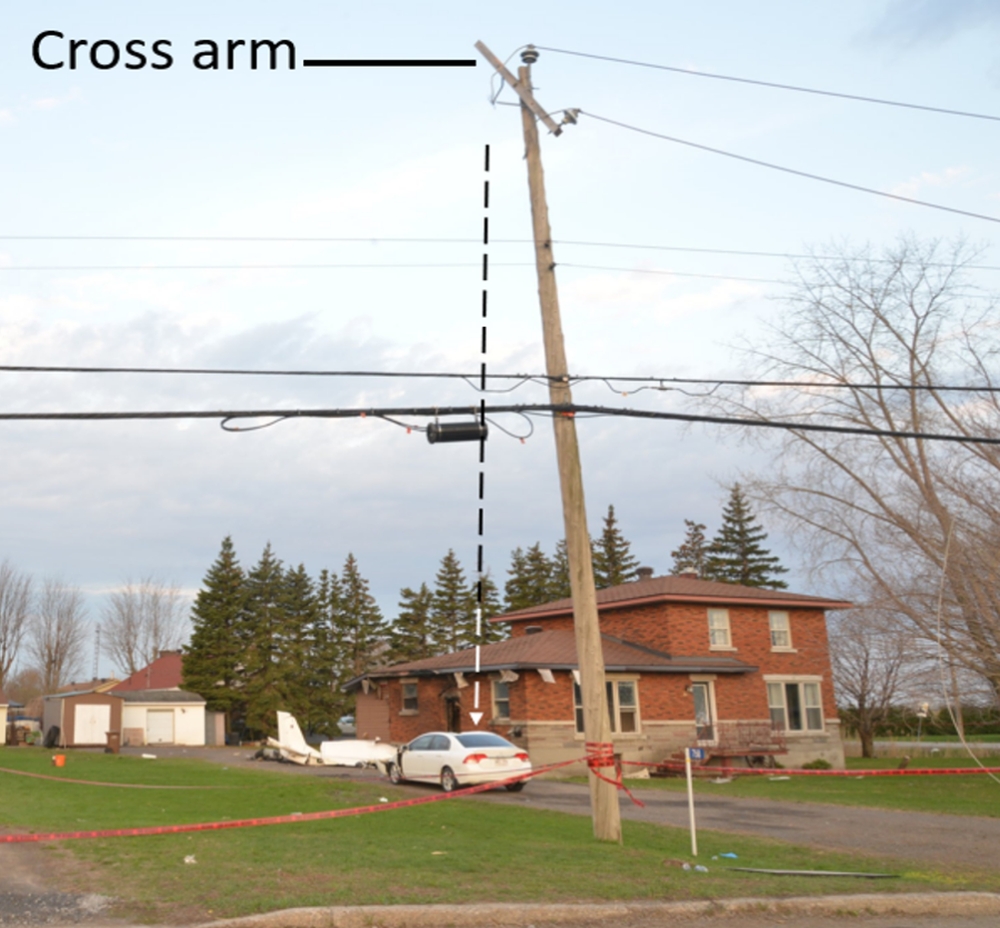

The angle formed by a line drawn between the top part of the hydro pole near the house and the automobile was approximately 45° (Figure 1), suggesting that the aircraft’s horizontal speed was low when it collided with the power lines.

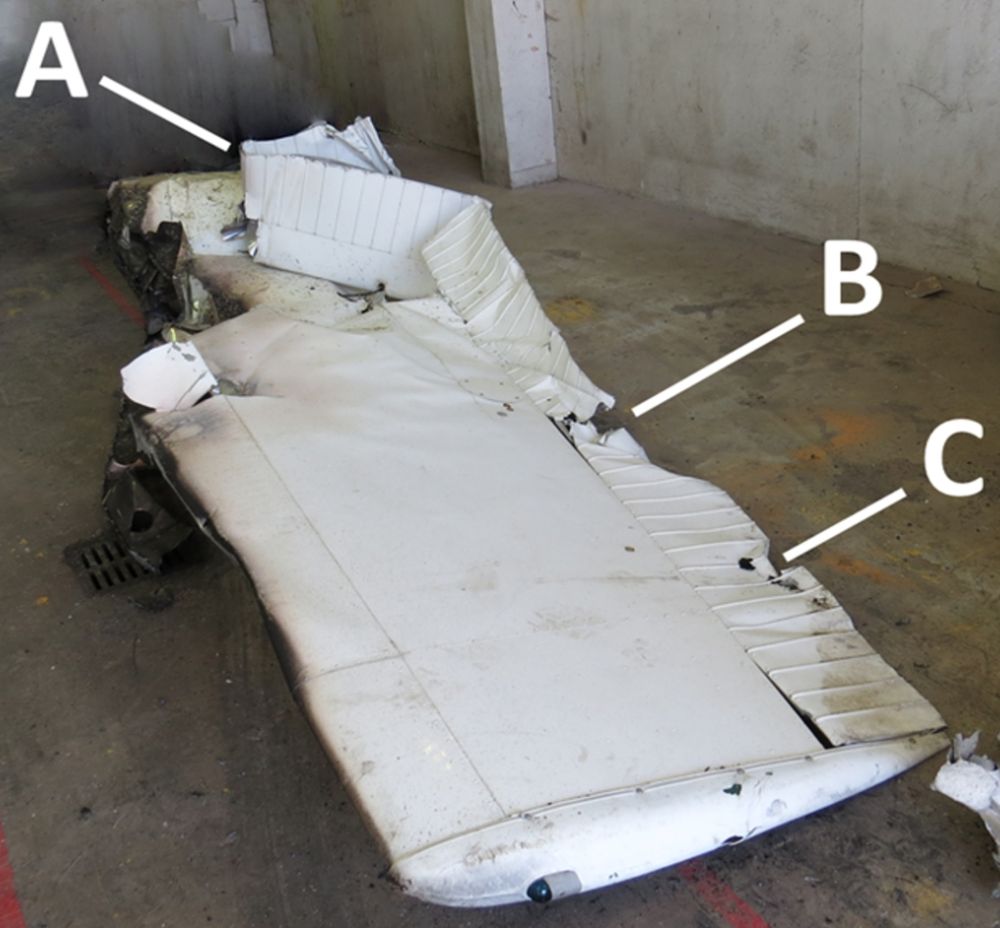

The examination of the aircraft’s right wing revealed 3 dents along the trailing edge (Figure 2): 2 consistent with an impact with a power line (A and C) and the other one (B) consistent with an impact with the cross arm of the hydro pole. The left wing did not exhibit any damage due to impact with the power lines or the hydro pole.

Flight training

Flight training for a private pilot licence – aeroplane requires the completion of a minimum of 45 hours of flight, with a minimum of 17 hours dual instruction flight time and 12 hours solo flight time.Footnote 4 These flight times must be entered in the pilot training record, along with ground school instruction.

The occurrence pilot’s training record was kept and updated by the flight instructor. It indicated that the student pilot had accumulated 20.8 hours of dual instruction flight and 142.5 hours of solo flight. The Ground School Instruction Record section of the record had no entries, and there was no evidence to confirm that the student pilot had begun the ground school instruction provided online by IKAROS.

Training flights were conducted from IKAROS’s base at the Montréal/St-Lazare Aerodrome (CST3), Quebec, until 24 August 2022. On that date, the student pilot had accumulated a total of 14.8 hours of dual instruction flight and 26.6 hours of solo flight.

The student pilot then conducted his solo flights from the St-Mathieu-de-Laprairie Aerodrome (CML8), Quebec, 27 nautical miles east of CST3, because this is where he usually parked his personal aircraft (the occurrence aircraft). Given that the instructor was not at CML8, he remotely authorized the solo flights.

Direction and supervision of solo training flights

The holder of a student pilot permit is authorized to conduct a solo training flight if the following conditions are met:

- the flight is conducted for the purpose of the holder’s flight training;

- the flight is conducted in Canada;

- the flight is conducted under day VFR;

- the flight is conducted under the direction and supervision [emphasis added] of a person qualified to provide training toward the permit, licence or rating for which the pilot-in-command experience is required; and

- no passenger is carried on board.Footnote 5

The TSB investigated a helicopter collision with terrain that occurred on 19 November 2018, in which a student pilot was conducting a solo training flight under the supervision of a freelance instructor.Footnote 6 Although the term “direction” is not defined in the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs), during the investigation, TC indicated that it considered the term “direction” to mean instructions and directives that the instructor gives to the trainee regarding expectations for the training flight. Thus, the trainee may not decide on how the flight is carried out or simply do what they want. This TC interpretation is in line with the definition of a pre-flight briefing.Footnote 7 According to CARs 405.31,

No person shall commence a training flight unless the trainee has received from the flight instructor

- a pre-flight briefing; and

- where new flight exercises are to be conducted during the flight, preparatory ground instruction.Footnote 8

In the months preceding the occurrence, the instructor accepted that the student pilot was regularly flying for his own pleasure and often provided no directives regarding exercises to practise in flight. The instructor had also informed him that his student pilot permit did not allow him to carry passengers. However, the student pilot regularly took a passenger on solo flights without notifying his instructor.

On the day of the occurrence, the instructor checked the weather conditions for the CML8 area and did not give the student pilot any directives. He did not know the planned take-off and landing times or the flight route planned by the student pilot. He was also unaware that the aircraft had been parked on a private property in Saint-Urbain-Premier for at least 1 week. Furthermore, no flight plan or flight itinerary was filed for the occurrence flight.

During the 2018 TSB investigation mentioned above, TC indicated that it allowed direction and supervision to be done remotely for solo training flights. However, TC was of the opinion that remote supervision should only be done occasionally and that remote supervision for every solo flight was not a good practice.

After the instructor had begun acting as a freelance instructor, the student pilot accumulated 26.3 flight hours, all for solo and remotely supervised flights.

The student’s training was being conducted in accordance with subparagraph 406.03(2)(b)(i) of the CARs, which does not require freelance instructors to notify TC of their training activities, making regulatory oversight of these instructors difficult. The only time that a TC inspector would normally provide regulatory oversight of a freelance instructor is when an official complaint is received regarding a poor practice, or when the inspector becomes aware of an accident or incident that occurs during flight training. TC must therefore count on freelance instructors to comply with regulations in effect and to follow best practices.

In this occurrence, TC was informed on 16 June 2022 that the student pilot was receiving flight training on an aircraft other than IKAROS’s aircraft and that flight training was being conducted from CST3. However, no further updates were sent to TC.

Low-flying and flying over a built-up area or an assembly of persons

When flying at lower altitudes is required to practise an exercise such as a diversion during a cross-country flight, it must be conducted in compliance with the regulations in effect.

The CARs stipulate the following:

[...] an aircraft shall be deemed to be operated over a built-up area or over an open-air assembly of persons if the built-up area or open-air assembly of persons is within a horizontal distance of:

- 500 feet from a helicopter or balloon; or

- 2,000 feet from an aircraft other than a helicopter or balloon.Footnote 9

Furthermore, according to the CARs, no person shall operate an aircraft over a built-up area or over an open-air assembly of persons at an altitude that is lower than 1000 feet above the highest obstacle located within a horizontal distance of 2000 feet, with the exception of a takeoff, approach, or landing.Footnote 10 However, the terms “built-up area” and “assembly of persons” are not defined.

In this occurrence, the aircraft flew over a residential area and an assembly of 15 or so persons at less than 500 feet above ground level, and at a horizontal distance of less than 2000 feet.

Low-speed manoeuvre and stall in flight

When an aircraft flies at a certain airspeed, the airflow around the wings creates the lift necessary to raise and maintain the aircraft in the air. If the aircraft’s airspeed drops below the minimum needed to create enough lift, the aircraft can no longer be maintained in flight and stalls.

The stall speed varies based on several factors such as the aircraft’s angle of bank and flap position. The Cessna Model 150 Owner’s Manual contains the calibrated stalling speedsFootnote 11 (CAS) when the aircraft weighs 1600 pounds and power is off (Figure 3) as well as an indicated airspeed (IAS) correction tableFootnote 12 (Figure 4).

The occurrence aircraft was equipped with a stall warning system, which worked properly during stall exercises carried out in the presence of the instructor, the last of which had been conducted on 15 February 2023. According to the owner’s manual, a steady aural signal is produced 5 to 10 mph before the actual stall speed is reached.Footnote 13

In order for an aircraft to recover from a stall, its altitude must be high enough to allow the pilot to execute the recovery manoeuvre because a loss of altitude can be expected. Therefore, if the flight is conducted too close to the ground, the height available above the ground may be insufficient to enable flight recovery after a stall.

According to information gathered during the investigation and the examination of the accident site, the aircraft was in a near-vertical descent after conducting a low-speed manoeuvre, a situation that corresponds to a stall.

Safety messages

It is important that pilots respect the distance and altitude requirements for flying over a built-up area or an assembly of persons, given that these requirements provide a minimum safety margin to protect persons and property on the ground if low-level manoeuvres are conducted or flight issues occur.

Student pilots are reminded that solo flights are authorized only for practising training manoeuvres necessary to obtain a pilot permit or licence.

To ensure the safety of training flights, including solo flights, instructors must evaluate and reinforce the adoption and implementation of good airmanship practices by student pilots. It is essential that instructors actively direct and supervise such solo flights; however, this can be challenging if student pilots use their own aircraft and if instructors supervise the flights remotely.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s investigation into this occurrence. The Board authorized the release of this report on . It was officially released on .

![Stalling speeds depending on the aircraft’s angle of bank and flap position when the aircraft has a gross weight of 1600 pounds and power is off (Source: Cessna Aircraft Company, <em>Cessna Model 150 Owner’s Manual</em> [1967], Section V: Operational Data, Figure 5-2)](/sites/default/files/eng/rapports-reports/aviation/2023/a23q0041/images/a23q0041-figure-03.jpg)

![Correction table showing indicated airspeeds and calibrated airspeeds with flaps up and down (Source: Cessna Aircraft Company, <em>Cessna Model 150 Owner’s Manual</em> [1967], Section V: Operational Data, Figure 5-1)](/sites/default/files/eng/rapports-reports/aviation/2023/a23q0041/images/a23q0041-figure-04.jpg)