Lateral runway excursion

Propair Inc.

Beech King Air A100, C-GJJF

Wemindji Airport (CYNC), Quebec

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

On 04 November 2023, the Beech King Air A100 aircraft (registration C-GJJF, serial number B-123), operated by Propair Inc., was conducting a medical evacuation flight under instrument flight rules, from Rouyn-Noranda Airport (CYUY), Quebec, to Wemindji Airport (CYNC), Quebec, with 2 pilots and 3 mission personnel on board. At 0227 Eastern Daylight Time, the aircraft touched down slightly left of the centreline of Runway 28 at CYNC. The left propeller and main landing gear then struck a snow windrow that extended along the entire length of the runway. The aircraft exited to the left of the runway and came to rest in the snow approximately 45 feet from the edge of the runway. One member of the mission personnel received minor injuries. The aircraft’s left propeller and engine were damaged, as were the flaps on both sides.

1.0 Factual information

1.1 History of the flight

1.1.1 Background

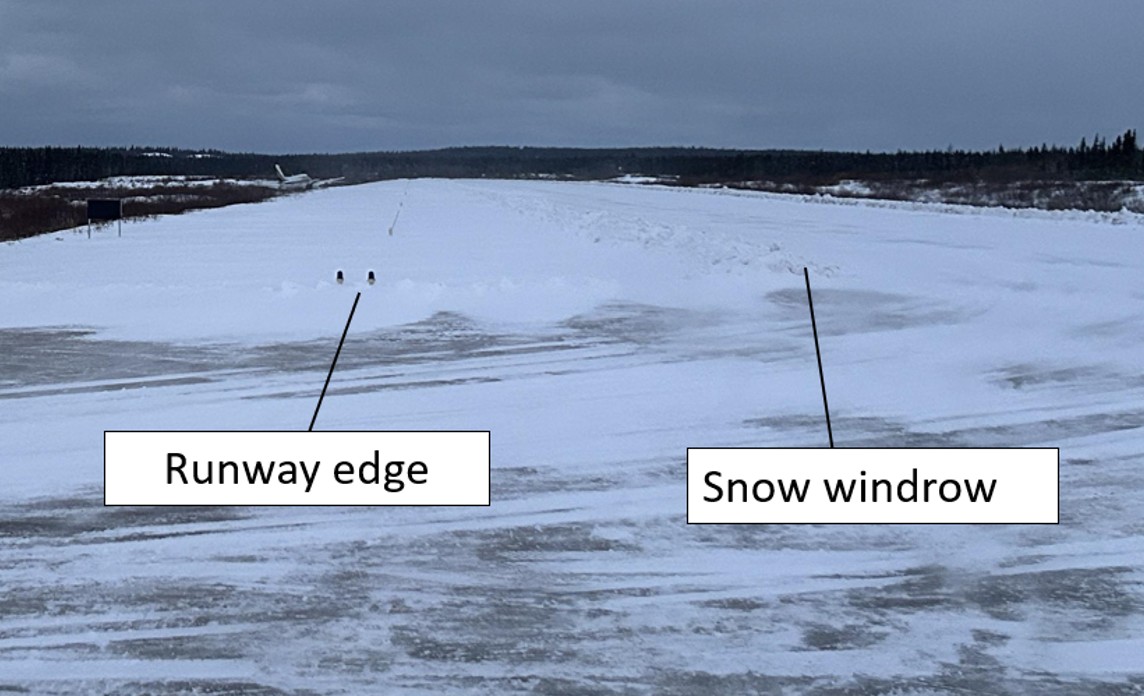

On the morning of 03 November 2023, the vehicle operator responsible for winter maintenance at Wemindji Airport (CYNC)All locations are in the province of Quebec, unless otherwise indicated., began his shift at 0800All times are Eastern Daylight Time (Coordinated Universal Time minus 4 hours). and was the only person working at the airport that day. Given that snow had fallen overnight, he began to remove snow from the runway.CYNC has a single runway, Runway 10/28. He did this in an asymmetrical pattern, over a width of approximately 65 feet, leaving 2 windrows, each about 18 inches high. One windrow was encroaching 23 feet onto the southern edge of the runway, while the other was encroaching 12 feet onto the northern edge of the runway. Estimating that the snow had been sufficiently removed, he moved on to other tasks in preparation for flights happening that day.

The airport register indicated that the daily inspection of facilities, including movement areas, had been completed by the vehicle operator on the morning of 03 November, after the snow had been removed, and nothing unusual had been noted.

At 1530, the 1st aircraft with a scheduled flight landed on Runway 28. The pilot told his colleague, who was following in a 2nd aircraft, that the runway was narrow. Believing that he would not be able to turn around on the runway width available, the pilot continued to the end of the runway so that he could turn around and backtrack to the terminal. The 2nd aircraft also landed without incident, and the pilot turned around on the runway to return to the terminal.

Neither of these pilots reported the snow windrows on the runway to either the airport operator or NAV CANADA.

A runway surface condition NOTAM (RSC NOTAM) was issued at 1620. Valid for 24 hours, the RSC NOTAM reported the following conditions:

- a mix of compacted snow and gravel over 80% of the runway width;

- 1/8 inch of wet snow over 20% of the width.

At 2033, Propair Inc.’s (Propair’s) dispatch received a call from the aeromedical evacuation coordination centre requesting a flight from CYNC to Chisasibi Airport (CSU2). A crew consisting of 2 pilots and 3 mission personnel was assigned to the flight. The captain arrived at Rouyn-Noranda AirportPropair is based in Rouyn-Noranda. (CYUY), at around 2230 to prepare for the flight to CYNC and the medical evacuation (MEDEVAC) flight from CYNC to CSU2. The RSC NOTAM for the runway at CYNC and the weather conditions and forecasts for CYNC and CSU2 were checked. Given that weather conditions were poor at CSU2, a decision was made to conduct the medical evacuation to Montréal/Pierre Elliott Trudeau International Airport (CYUL).

At around midnight on 04 November, the CYNC vehicle operator inspected the runway in anticipation of the arrival of 2 Propair MEDEVAC flights during the night, with the 2nd being the occurrence aircraft. The operator noted that there had been no change in the conditions compared to those observed when he had left at the end of the afternoon, some 8 hours earlier.

At approximately 0014, the 1st flight took off from CYUY bound for CYNC, as flight PRO4200M.

1.1.2 Occurrence flight

At 0054, the occurrence aircraft, a Beech King Air A100, took off from Runway 26 at CYUY bound for CYNC to conduct the MEDEVAC flight as flight PRO4215M, with the crew assigned by the company’s dispatch on board. The captain, who was seated on the left, was the pilot flying (PF). The pilot seated on the right also had a captain rating on type but was acting as first officer and pilot monitoring (PM) for the occurrence flight.

At approximately 0115, the Propair dispatch contacted CYNC staff to report that 2 flights were en route. The person at CYNC who responded did not mention anything out of the ordinary to Propair at this time.

At 0145, flight PRO4200M landed without incident on Runway 28 at CYNC. The pilot on the ground contacted the pilot of flight PRO4215M to provide a pilot weather report, but did not mention the runway conditions.

At 0208, 23 minutes after flight PRO4200M had landed without incident, flight PRO4215M began its descent for an area navigation approach to Runway 28.

The approach was conducted in accordance with the criteria set out in the company’s standard operating procedures (SOPs) and the pilot’s operating manual (POM). The aircraft crossed the runway threshold at a height of approximately 30 feet and touched down on the runway about 400 feet beyond the threshold at 0227, slightly to the left of the normal runway centreline, but within lateral boundaries of the runway. Shortly after touchdown, the left main landing gear and propeller struck a snow windrow that was on the runway and extended along the entire length of the runway (Figure 1).

The aircraft then swerved to the left and exited the runway. It came to rest in the snow approximately 45 feet from the left edge of the runway (Figure 2).

The pilots secured the aircraft, and the occupants were able to exit through the door. One member of the mission personnel received minor injuries but was able to evacuate the aircraft without assistance. The vehicle operator, who was at the terminal, quickly drove to the site and drove the occupants to the terminal in his vehicle. The aircraft sustained minor damage.

1.2 Injuries to persons

Two pilots and 3 mission personnel were on board. Table 1 outlines the degree of injuries received.

Degree of injury | Crew | Passengers | Persons not on board the aircraft | Total by injury |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Fatal | 0 | 0 | – | 0 |

Serious | 0 | 0 | – | 0 |

Minor | 0 | 1 | – | 1 |

Total injured | 0 | 1 | – | 1 |

1.3 Damage to aircraft

The left propeller and engine, as well as the flaps on both sides, were slightly damaged by the impact with the snow windrow.

1.4 Other damage

A runway edge light was dislodged during the runway excursion.

1.5 Personnel information

1.5.1 Flight crew

Captain | First officer | |

|---|---|---|

Pilot licence | Commercial pilot licence – aeroplane (CPL) | Commercial pilot licence – aeroplane (CPL) |

Medical expiry date | 01 October 2024 | 01 October 2024 |

Total flying hours | 1134.1 | 1320.1 |

Flight hours on type | 700.6 | 423.5 |

Flight hours in the 24 hours before the occurrence | 1.7 | 0 |

Flight hours in the 7 days before the occurrence | 6.1 | 24.5 |

Flight hours in the 30 days before the occurrence | 54.2 | 79.7 |

Flight hours in the 90 days before the occurrence | 138.7 | 164 |

Flight hours on type in the 90 days before the occurrence | 138.7 | 164 |

Hours on duty before the occurrence | 3.9 | 3.9 |

Hours off duty before the work period | 104.6 | 50 |

The captain and first officer held the appropriate licence and ratings for the flight in accordance with existing regulations.

1.5.2 Vehicle operator responsible for winter maintenance

Date hired by the airport | 31 October 2023 |

|---|---|

Employment status | Seasonal |

Restricted Radio Operator Certificate – Aeronautical (ROC-A) | 30 July 2021 |

Experience at aerodromes | A few replacement jobs from September 2015 to December 2015 |

Hours on duty before the occurrence | Approximately 2 hours 30 minutes* |

Hours off duty before the work period | Approximately 8 hours |

* The vehicle operator had finished his workday around 1600 the previous day and had returned to the airport around midnight to inspect the runway in anticipation of the 2 MEDEVAC flights.

The vehicle operator responsible for winter maintenance on the day of the occurrence had been working at the airport for a few days and had not yet received any official training (see section 1.18.3.3.2 Training and supervision).

1.6 Aircraft information

Manufacturer | Beech Aircraft Corporation* |

|---|---|

Type, model, and registration | King Air A100, C-GJJF |

Year of manufacture | 1972 |

Serial number | B-123 |

Certificate of airworthiness issue date | 13 November 1987 |

Total airframe time | 29 141.7 hours |

Engine type (number of engines) | Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6A-28 (2) |

Propeller type (number of propellers) | Hartzell Propeller Inc. HC-D4N (2) |

Maximum allowable take-off weight | 12 008 lb (5446 kg) |

Recommended fuel type(s) | Jet A, Jet A-1, Jet B |

Fuel type used | Jet A |

* Textron Aviation Inc. currently holds the type certificate for this aircraft.

There were no recorded outstanding defects in the aircraft’s journey log at the time of the occurrence. There was no indication that a component or system malfunction played a role in this occurrence.

The aircraft’s weight and centre of gravity were within the prescribed limits.

1.7 Meteorological information

The limited weather information system (LWIS) report issued at 0200 on 04 November for CYNC stated the following conditions:

- Winds from 270° true (T) at 13 knots

- Temperature −4 °C and dew point −6 °C

- Altimeter setting 29.85 inches of mercury (inHg)

The conditions reported by the LWIS at midnight, which were used by the pilots for flight planning purposes, were the following:

- Winds from 290°T at 15 knots, gusting to 22 knots

- Temperature −4 °C and dew point −6 °C

- Altimeter setting 29.82 inHg

The weather at the time of landing was not considered to be a factor in this occurrence.

1.8 Aids to navigation

Not applicable.

1.9 Communications

Not applicable.

1.10 Aerodrome information

CYNC has 1 runway, Runway 10/28, which is gravel. It is 3511 feet long and 100 feet wide, and is lit by a type K, variable intensity aircraft radio control of aerodrome lighting (ARCAL) system. This runway is connected to Taxiway A, which is also gravel.

CYNC has a community aerodrome radio station, available Monday through Friday and on Sundays at set times, up to 2200 at the latest, to provide pilots with aviation support services, including weather and communication services.

1.11 Flight recorders

The aircraft had 2 GTN 650 global positioning system (GPS) units manufactured by Garmin.

The aircraft was also equipped with a cockpit voice recorder (CVR), which had a recording capacity of 120 minutes.

The 3 units were sent to the TSB Engineering Laboratory in Ottawa, Ontario, for examination. Flight path and speed data for the occurrence flight were downloaded from the memory cards in the GPS units. The CVR data were successfully downloaded and contained audio recordings for the occurrence flight.

1.12 Wreckage and impact information

The GPS data gathered, and photos of the occurrence site helped to determine that after touchdown, 1.8 seconds passed before the left main landing gear wheel and the propeller of the left engine struck the snow windrow on the runway. The aircraft then swerved left, exited the runway, and came to rest on its wheels 1000 feet beyond the threshold and 45 feet beyond the edge of the runway.

1.13 Medical and pathological information

There is no indication that either the flight crew’s performance or the vehicle operator’s performance were negatively affected by medical or physiological factors. Based on a review of the flight crew’s work and rest schedule, there was no indication that the crew’s performance was degraded by fatigue.

1.14 Fire

There was no indication of fire either before or after the occurrence.

1.15 Survival aspects

Not applicable.

1.16 Tests and research

1.16.1 TSB laboratory reports

The TSB completed the following laboratory reports in support of this investigation:

- LP154/2023 – NVM Recovery – GPS and Transponders

- LP173/2023 – CVR Audio Recovery

1.17 Organizational and management information

1.17.1 Propair Inc.

Propair holds an air operator certificate (AOC) and conducts its activities in accordance with the requirements of subparts 703 (Air Taxi Operations) and 704 (Commuter Operations) of the Canadian Aviation Regulations (CARs). The occurrence flight was being conducted pursuant to Subpart 703. The company also holds an approved maintenance organization certificate issued under CARs Subpart 573.

The company offers charter services for passengers and cargo, as well as an aeromedical transportation service. Propair is the main provider of MEDEVAC flights for the Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay.

1.17.2 NAV CANADA

NAV CANADA provides air navigation services in Canadian airspace. The Minister of Transport has delegated to NAV CANADA “[t]he responsibility for the collection, evaluation, and dissemination of aeronautical information”Transport Canada, TP 14371E, Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM), effective 05 October 2023 to 21 March 2024, MAP – Aeronautical Charts and Publications, section 1.0: General Information. and “[t]he responsibility for the provision of aviation weather services in Canadian airspace,”Ibid., MET – Meteorology, section 1.1: General. NAV CANADA is the main source of information available for flight planning purposes; it has a website dedicated to flight planning.NAV CANADA, Flight Planning, at https:// https://spaces.navcanada.ca/workspace/flightplanning/ (last accessed on 29 December 2025).

1.17.3 Wemindji Airport

CYNC is one of the Canadian airports that are owned and operated by Transport Canada (TC) under an airport certificate. However, TC subcontracts a portion of the airport’s administration, operation, and maintenance to the Cree Nation of Wemindji.

1.17.3.1 Airport operator

When an airport operator is a corporation, as is the case here, airport management is delegated to an individual: the airport manager.

The CARs use the term principal to refer to this person, and define it as follows:

principal means: [...]

h) in respect of an airport:

(i) any person who is employed or contracted by its operator on a full- or part-time basis as the airport manager, or any person who occupies an equivalent position;

(ii) any person who exercises control over the airport as an owner; and

(iii) the accountable executive appointed by its operator [...].Transport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations, paragraph 103.12(h).

Contrary to similar positions with air operators and approved maintenance organizations, the airport manager position does not have any minimum requirements in terms of relevant experience or specific qualifications under the regulations.

1.17.3.2 Staff

1.17.3.2.1 Transport Canada

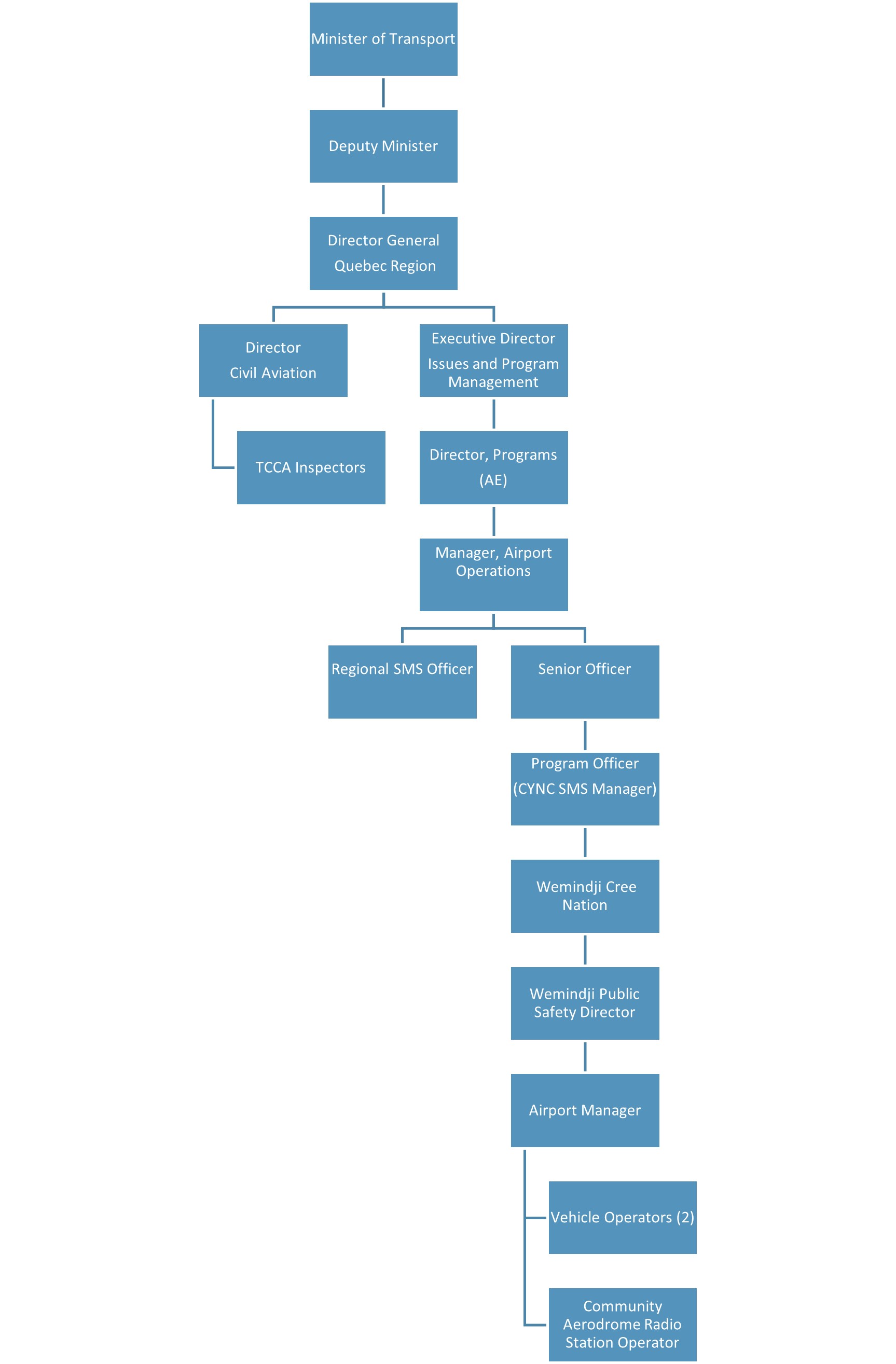

As the airport operator, TC appoints staff members as delegated officers and assigns them responsibility for one or more airports. In the case of CYNC, the airport manager is the person who has administrative and financial authority, or the accountable executive (AE). The AE reports to the Executive Director, Issues and Program Management, who reports to the Office of the Regional Director General – TC Quebec Region (Appendix A).

This AE, who has the highest level of responsibility for airport operations, is also in charge of all activities covered by the operator certificates and of maintaining the safety management systems (SMSs) at airports owned and operated by TC in the Quebec Region.In total, TC owns 14 airports (11 small and 3 large) in Quebec and operates 11 of them.

Furthermore, the TC staff below, who report to the AE, all have responsibilities related to TC airports:

- Manager, Airport Operations

- Regional SMS Officer

- Airport Operations Senior Officer

- Program Officer (SMS Manager).

1.17.3.2.2 Cree Nation of Wemindji

The Cree Nation of Wemindji is an Indigenous community in Quebec with roughly 1600 residents;In 2021, there were 1562 residents in the community according to census data from that year. it is located on the eastern shore of James Bay. Its band council consists of 7 elected council members who determine the community’s direction and supervise the various departments in the community.

The Cree Nation of Wemindji signed a subcontract with TC for certain aspects of CYNC management. Under the terms of the contract, staff working at the airport, including the airport manager, are hired and supervised by the Cree Nation. Staff working at the airport report to the Cree Nation Department of Public Safety.

At the time of the occurrence, the airport had 4 employees:

- Airport manager

- 2 vehicle operators

- Community aerodrome radio station operator

1.17.3.2.3 Staffing-related issues

From March 2022 to July 2023, there was significant staff turnover in the TC Airport Operations team. There was a wave of departures of people occupying many key positions in the spring of 2022. The hiring of the employees to fill these positions spanned over 2022 and 2023, which left many positions unoccupied for long periods:

- A senior officer had been hired in July 2022, 1 month after the position had been vacated. This officer’s integration process was not structured. From the time he occupied the position, he had to make do with a reduced workforce and take on numerous responsibilities, including those of regional SMS officer and program officer, in addition to performing some of the tasks from his former position.

- There were 3 successive acting regional managers, Airport Operations, from March 2022 to January 2023, when the position was filled permanently.

- The program officer position, which had been vacant since November 2022, was filled in April 2023.

- The regional SMS officer position remained vacant from May 2022 to July 2023, that is more than 1 year, before it was filled.

This situation increased the workload for existing staff and made the integration of new staff more difficult. At the time of the occurrence, some of the positions had been filled for less than 1 year.

The departure of experienced staff inevitably leads to a loss of organizational knowledge. To limit the effects, an integration period that includes adequate training in the tasks to be performed as well as support from an experienced person is essential. According to the information gathered during the investigation, this integration period could not be ensured in most cases because there was not enough staff available to train the new employees.

The Cree Nation of Wemindji also regularly faces issues with the staff responsible for the operation of CYNC. Recruiting local staff, whether seasonal (as is the case for snow removal vehicle operators) or permanent, was cited as a recurring problem. At the time of the occurrence, the airport manager position had been vacant and filled on an acting basis since November 2022.

1.17.4 Transport Canada Civil Aviation Directorate

1.17.4.1 Mission

TC Civil Aviation (TCCA) implements and manages TC’s Aviation Safety Program across Canada by means of an aviation safety regulatory framework and of aviation safety oversight.Transport Canada, Transport Canada Civil Aviation Program Manual for the Civil Aviation Directorate, Issue 5 (27 July 2021).

TCCA’s mission is:

To develop and administer policies and regulations for the safest civil aviation system for Canada and Canadians using a systems approach to managing risks.Ibid., section 4.3(1): TCCA’s vision and mission, p. 8.

TCCA prefers to use a systems approach to managing risks because it “promotes transparent processes that establish clear lines of accountability for decision-making.”Ibid., section 4.3(4): TCCA’s vision and mission, p. 9.

This approach is intended to be used in the development of policies and regulations, but also in the administration of those policies and regulations—in other words, in TCCA oversight activities.

It is up to TCCA, to ensure that all stakeholders, and in particular airport operators, comply with regulations in effect and applicable safety standards.

1.17.4.2 Organizational structure

At the time of the occurrence, TCCA was being led by a Director General and an Associate Director General. It consisted of a headquarter and 5 regional branches.

The regional branches are operational units responsible for aviation safety oversight at companies that hold a Canadian aviation document and are generally headquartered in their region, as well as other operators, such as airport operators. Their quality assurance and data analysis activities improve the oversight program. They also have regional enforcement units, which may take punitive action to enforce the law.Ibid., Appendix A (9) – TCCA organizational descriptions, p. 22.

(4) Regional directors have a line reporting relationship with a regional Director General and a functional reporting relationship with the Director General and Associate Director General, Civil Aviation. […]

(5) The functional relationship allows the Director General, Civil Aviation (DGCA) to provide direction within the scope of the Civil Aviation Directorate. The line relationship signifies a command over resources and activities.Ibid., sections 4.5(4) and (5): Organizational structure, pp. 9 and 10.

The AE position at Wemindji Airport reports to the Executive Director, Issues and Program Management who in turn reports to the Regional Director General – Quebec region. Similarly, the Director, Civil Aviation for the Quebec region also reports directly to the Regional Director General – Quebec region (Appendix A).

1.18 Additional information

1.18.1 Flight planning

1.18.1.1 General

Regardless of the type of flight operations, flight planning is a crucial step in flight safety. It is when all of the elements needed for the flight must be gathered and reviewed.

According to section 602.71 of the CARs, “[t]he pilot-in-command of an aircraft shall, before commencing a flight, be familiar with the available information that is appropriate to the intended flight.”Transport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations, section 602.71.

For general aviation aircraft, flight planning is carried out by the pilot and is often limited to the use of aviation information available in NAV CANADA aeronautical information publications and on various websites.

For commercial air operators and some private operators, pilots have more resources available to them, such as the company operations manual and SOPs. Pilots may also have the assistance of a flight coordination service for flight planning and execution.

One of Propair’s dispatch centre’s responsibilities is to manage requests for medical evacuations. For the occurrence flight, the dispatcher coordinated with the client and assigned a team for the mission. Flight planning, including consultation of aeronautical information, is the flight crew’s responsibility.

1.18.1.2 Aeronautical information

NAV CANADA, which is responsible for distributing aeronautical information in Canada, publishes various aeronautical information products based on the nature and validity period of the information being published.

Notices known as NOTAMs are issued to distribute operationally significant information that is of a temporary nature and of short duration, which includes information on runway conditions.Transport Canada, TP 14371E, Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM), effective 05 October 2023 to 21 March 2024, MAP – Aeronautical Charts and Publications, section 3.1: General. In that case, NAV CANADA issues a runway surface condition (RSC) NOTAM “to alert pilots to natural winter surface contaminants […] that could affect aircraft breaking and other operational performance.”NAV CANADA, Terminav terminology database, at https://www1.navcanada.ca/logiterm/addon/terminav/termino_view.php?id=fa8bfe6d@6feeb229400e0a48af405086adcd5516&m=8b6f8e6d&fid=11461 (last accessed on 30 December 2025).

According to the Canadian NOTAM Operating Procedures:

The aerodrome operator or his/her delegate is responsible for the origination, revision and cancellation of NOTAMs pertaining to the following circumstances:

- any projection by an object through an obstacle limitation surface relating to the aerodrome;

- the existence of any obstruction or hazardous condition affecting aviation safety within the aerodrome boundaries;

- any change in the level of services at the aerodrome set out in an aeronautical information product and pertinent to aviation safety, excluding instrument procedures. […]

- the closure of the aerodrome or any part of the manoeuvring area of the aerodrome;

- the presence of contaminant on the movement area; […]

The Aerodrome Operator is responsible for providing runway surface conditions and quantitative braking action information to NAV CANADA. The information shall be either input directly at the site in an authorized web-based application or an authorized automated system, communicated in a written format using the AMSCR/CRFI [aircraft movement surface condition report/Canadian Runway Friction Index] form available from Transport Canada or NAV CANADA (or a similar paper or electronic format), or communicated verbally.NAV CANADA, Canadian NOTAM Operating Procedures, version 6.0 (20 April 2023), section 2.2.2: Aerodrome Operator, p. 19.

The NOTAM procedures also state that the “[c]leared width of the runway (if reduced)”Ibid., section 8.3.2: Item (E) – Runway Surface Condition Reporting by Full Runway Length, p. 129. must be indicated in an RSC NOTAM.

In this occurrence, an RSC NOTAM containing the information provided by the snow removal vehicle operator had been issued for CYNC. This NOTAM did not mention the presence of snow windrows on the runway or the reduced runway width.

1.18.2 Pilot decision making and situational awareness

Decision making in general is a cognitive process that involves identifying and choosing a course of action from several alternatives. Decision making for pilots occurs in a dynamic environment and includes 4 steps: gathering information, processing information, making decisions, and implementing the decisions. The U.S. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) defines aeronautical decision making as “a systematic approach to the mental process used by pilots to consistently determine the best course of action in response to a given set of circumstances. It is what a pilot intends to do based on the latest information he or she has.”Federal Aviation Administration, FAA-H-80803-25C, Pilot’s Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (2023), Chapter 2: Aeronautical Decision-Making, p. 2-1 at https://www.faa.gov/sites/faa.gov/files/04_phak_ch2.pdf (last accessed on 30 December 2025).

Situational awareness is an integral part of pilot decision making. Situational awareness is defined as the perception of the elements in the environment, the comprehension of their meaning and the projection of their status in the near future.M. R. Endsley, “Situation Awareness,” in: G. Salvendy and W. Karwowski (ed.), Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics, 5th Edition, (John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2021), pp. 434–435. In a dynamic environment, situational awareness requires extracting information from the environment, integrating this information with relevant internal knowledge to create a coherent mental model of the current situation, and using this mental model to predict future events.

Information on runway conditions is one of the elements that helps to create this mental model. Updated information is therefore essential to help the flight crew prepare accordingly and carry out a plan for a safe landing. The occurrence flight crew did not have this updated information, given that they were not informed of the snow windrows on the runway and were therefore unable to prepare accordingly. Furthermore, given that the occurrence took place at night, even though visibility was good, the flight crew did not see the snow windrows on the runway before landing, which was also the case for the flight crew of the flight that landed before them.

1.18.3 Airport operations in Canada

Airport operations in Canada are governed by Part III of the CARs, specifically Subpart 302, which states, in part, the requirements for the issuance of airport certificates and the obligations of airport operators. The related standardTransport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations, Standard 322: Airports. and recommended standards and practices are set out in the TC publication known as TP 312Transport Canada, TP 312E, Aerodrome Standards and Recommended Practices: Land Aerodromes, 5th Edition (effective 15 January 2020).,Pursuant to section 302.07 of the CARs, the various versions of TP 312 are in effect and applicable based on the date that the airport certificate was issued and the facilities were commissioned. It states these obligations.

As an airport certificate holder, TC is required to operate CYNC in accordance with the regulations and recommended standards and practices in effect.

1.18.3.1 Airport certificate and operations manual

Sections 302.02 to 302.06 of the CARs discuss how to obtain an airport certificate, and section 302.02 states that airport operators must submit an airport operations manual (AOM) to TC for approval when they apply for a certificate. The AOM “shall set out the standards to be met and the services to be provided by an airport operator.”Transport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations, subsection 302.08(3). It contains the airport operator’s policies and procedures, including those with respect to the SMS required under section 107.02 of the CARs.Ibid., paragraph 302.08(4)(f). In some respects, it is a written contract between the airport operator and TCCA; in the case of CYNC, it is between TC and TCCA. “The operator of an airport shall operate the airport in accordance with the airport operations manual.”Ibid., subsection 302.08(5).

According to subsection 302.08(1) of the CARs, the operator must maintain the AOM and have any proposed amendment approved by TCCA. Furthermore, the CYNC SMS Manual requires an annual review of the AOM.

The last amendment to the CYNC AOM was made in May 2017 and approved by TCCA on 24 July 2017.

1.18.3.2 Communication of information

Subpart 302 of the CARs sets out airport operator obligations with respect to the communication of information when certain situations arise at airports, including any hazardous condition such as an obstructed runway:

(2) Subject to subsection (3), the operator of an airport shall give to the Minister, and cause to be received at the appropriate air traffic control unit or flight service station, immediate notice of any of the following circumstances of which the operator has knowledge:

(a) any projection by an object through an obstacle limitation surface relating to the airport;

(b) the existence of any obstruction or hazardous condition affecting aviation safety at or in the vicinity of the airport;

(c) any reduction in the level of services at the airport that are set out in an aeronautical information publication;

(d) the closure of any part of the manoeuvring area of the airport; and

(e) any other conditions that could be hazardous to aviation safety at the airport and against which precautions are warranted.

(3) Where it is not feasible for an operator to cause notice of a circumstance referred to in subsection (2) to be received at the appropriate air traffic control unit or flight service station, the operator shall give immediate notice directly to the pilots who may be affected by that circumstance.Ibid., subsections 302.07(2) and (3).

In the case of CYNC, communication of information regarding movement surface conditions was delegated to the subcontractor, or more specifically, the airport manager, under the terms of the service contract.Transport Canada, Technical Specifications – Contract for the Administration, Operation and Maintenance of the Wemindji Airport, Wemindji, Quebec, Contract No. T3033-170060, RDIMS No 13695791 (March 2018), Appendix 3 – Description of Duties and Qualifications, p. 27.

Information on runway surface conditions at CYNC had been communicated to NAV CANADA the day before the occurrence. NAV CANADA had then published this information as an RSC NOTAM at 1620. The NOTAM made no mention of the presence of windrows on the runway or of the reduced runway width. Valid for 24 hours, it was still in effect when planning took place for the occurrence flight and when the occurrence took place.

1.18.3.3 Winter maintenance

Sections 302.410 through 302.419 of the CARs, and the related Standard 322, discuss winter maintenance at airports.

According to Standard 322:

[t]he objectives of airport winter maintenance planning are to minimize the effects of winter conditions and to establish requirements and procedures pursuant to the Canadian Aviation Regulations to prevent or eliminate hazardous conditions in order to maintain safe aircraft operations.Transport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations, Standard 322: Airports, division IV –Airport Winter Maintenance: Foreword.

1.18.3.3.1 Winter maintenance plan

Section 302.410 of the CARs sets out an airport operator’s obligation to develop a winter maintenance plan, review it at least once a year, amend it as necessary, and inform the affected staff.

Section 302.411 of the CARs states the elements that must be included in the plan, including the following:

(b) a description of the winter maintenance operations to be carried out in an airside area once it is identified as a priority 1 area, priority 2 area or priority 3 area;

(c) communication procedures that meet the requirements of subsection 322.411(2) of the Airport Standards — Airport Winter Maintenance;

(d) procedures for publishing a NOTAM in the event of winter conditions that might be hazardous to aircraft operations or affect the use of movement areas and facilities used to provide services relating to aeronautics;Transport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations, section 302.411.[…]

The CYNC winter maintenance plan was approved in accordance with the regulations. It describes the policies, standards, guidelines, and responsibilities related to the removal of snow and ice from the movement areas of CYNC. According to the plan, the airport manager is responsible for directing, managing, and organizing snow and ice removal, ensuring that the required information is transmitted to the Québec Flight Information Centre (FIC), and coordinating the full or partial closure of the airport as necessary, based on specific criteria.Wemindji Airport, Winter Maintenance Plan 2023–2024 (version 8), p. 9. The snow clearing staff, meanwhile, are responsible for carrying out snow and ice removal also in accordance with a set of criteria and an established priority list. According to the list, the top priority is to clear the runway along its entire length and width. During snowstorms, however, the runway may be cleared to a minimum width of 80 feet, with the aim of clearing the entire width as soon as possible.Ibid., pp. 11 and 12.

The winter maintenance plan and the AOM state that the snow clearing staff are also responsible for inspecting and evaluating runway conditions at least twice a day (in the morning and at the end of the day),Ibid., p. 16. maintaining close contact with the Québec FIC, and providing the Québec FIC with regular runway condition reports and transmitting all information required to ensure effective coordination of snow removal operations.Ibid., p. 10.

The CYNC winter maintenance plan sets out the criteria for the frequency of aircraft movement surface condition reports (AMSCR), particularly when the cleared width of the runway falls below full width.Ibid., p. 16.

To summarize, the purpose of the winter maintenance plan is to provide guidance to the entire staff involved in winter operations at the airport and to ensure that movement areas are safe for aircraft, passengers, and vehicles. The plan is in effect during the winter, which extends from 01 November to 30 April.

From 2017 to 2023, annual reviews of the winter maintenance plan were carried out after 01 November, with the exception of 2019. For the 2021–2022 winter, the review took place toward the end of February 2022, which was close to the end of the season, and for winter 2023–2024, it took place on 30 November. The investigation was unable to determine whether the staff information sessions required after each annual review were being held during this period.

1.18.3.3.2 Training and supervision

Sufficient training is essential in a workplace to reduce hazards and manage risks associated with the use of equipment and the completion of tasks. This training is particularly important for airport snow removal staff, who must have access to all information necessary on equipment, safety procedures, and risk assessments associated with winter conditions.

Section 302.418 of the CARs discusses training for winter snow removal operations and states the following:

(1) The operator of an airport shall not assign duties in respect of its airport winter maintenance plan to a person unless that person has received training from the operator on those duties and on the matters set out in section 322.418 of the Airport Standards — Airport Winter Maintenance.

(2) The operator of the airport shall not assign supervisory duties in respect of its airport winter maintenance plan to a person unless that person has received training on those duties and on the content of the plan.

(3) Each year, before the start of winter maintenance operations, the operator of the airport shall provide persons who will be assigned duties in respect of its airport winter maintenance plan with training on any amendments that have been made to the plan since the previous winter.Transport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations, section 302.418.

In compliance with section 322.418 of the CARs Standard, CYNC’s winter maintenance plan stipulates that the airport manager must review the skills of workers, identify the airport’s needs, and provide training on the following subjects before the start of winter operations:

- The safe use of vehicles;

- Radio communication;

- Airport layout;

- The inspection, storage and application of sand;

- Procedures governing Aircraft Movement Surface Condition Reports (AMSCR), including observations, recording and transmission by NES [NOTAM entry system] (or by fax to the Quebec FIC);

- Methods for removing ice and snow from runway surfaces, runway and threshold lights, navigation aids, signage and windsocks;

- Familiarization with the Winter Maintenance Plan.Wemindji Airport, Winter Maintenance Plan 2023–2024 (version 8), p. 14.

Training must be competency-based and include a practical performance-based aspect.Transport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations, subsection 302.418(4).

In addition, new employees at CYNC must receive training on:

- Aerodrome Standards and Recommended Practices (TP 312)

- Winter Maintenance

- Emergency Measures

- Wildlife Management

- Human Factors

- Safety Management System (SMS).Transport Canada, Technical Specifications – Contract for the Administration, Operation and Maintenance of the Wemindji Airport, Wemindji, Quebec, Contract No. T3033-170060, RDIMS No. 13695791 (March 2018), section 3.8, p. 19.

The snow removal vehicle operator on duty the day of the occurrence had been hired a few days before and had not yet received training. He was the only employee working that day.

The CYNC acting airport manager at the time of the occurrence had been a vehicle operator before taking on the duties of airport manager in November 2022. He had received the required snow removal training in February 2019. However, he was travelling on the day of the occurrence, and no one was replacing him.

1.18.3.4 Safety and risk management

1.18.3.4.1 Safety management system

Safety has always been paramount at airports, but the introduction of SMSs has changed how it is managed. An SMS introduces a systemic risk management framework that has a safety oversight element, which should help to manage risks proactively and reactively.

Since early 2008, SMSs have been mandatory for airports pursuant to sections 107.01 and 107.02 of the CARs. The holder of an airport certificate issued under section 302.03 of the CARs “shall establish and maintain a safety management system.”Transport Canada, SOR/96-433, Canadian Aviation Regulations, section 107.02. This system shall include:

(a) a safety policy on which the system is based;

(b) a process for setting goals for the improvement of aviation safety and for measuring the attainment of those goals;

(c) a process for identifying hazards to aviation safety and for evaluating and managing the associated risks;

(d) a process for ensuring that personnel are trained and competent to perform their duties;

(e) a process for the internal reporting and analyzing of hazards, incidents and accidents and for taking corrective actions to prevent their recurrence;

(f) a document containing all safety management system processes and a process for making personnel aware of their responsibilities with respect to them;

(g) a quality assurance program;Ibid., section 107.03.

TCCA has developed an SMS implementation framework that has 4 phases and includes the following 6 components:

- Safety management plan

- Document management

- Safety oversight

- Training

- Quality assurance

- Emergency preparedness.Transport Canada, Advisory Circular (AC) 300-02: Safety Management System Implementation Procedures for Airport Operators (Issue 04: 05 June 2009), p. 4, at https://tc.canada.ca/sites/default/files/2022-02/300-002_e.pdf (last accessed on 06 January 2026).

Each component has one or more elements that need to be put in place during specific phases.

CYNC developed its SMS in accordance with the regulations and combined all relevant, required information in a complete reference manual. For the purposes of this investigation, given the COVID-19 pandemic and the fact that evaluation of phase IV, completed in June 2016, was the final step in the implementation of the SMS, the TSB’s examination went as far back as this phase.

1.18.3.4.2 Wemindji Airport Safety Management System Manual

The CYNC SMS ManualTransport Canada, Safety Management System Manual – Wemindji Airport, RDIMS No. 5574410-v11 (30 August 2018). explains the fundamentals of safety management, that is, a safety culture and a proactive approach, as well as the policies implemented to support these.

The Airport Safety Policy signed by the AE, on which the CYNC SMS is based, states the following:

The Airport Safety Management System is a proactive method of preventing and managing safety risks. Managing safety means identifying and mitigating risks before occurrences happen.Ibid., section 2.1: Airport Safety Policy, p. 7.

The manual also describes SMS roles and responsibilities, as well as procedures and processes, and provides guidelines for ensuring safety through a proactive culture, continuous improvement, and effective communications. It emphasizes integrating safety with financial management and human resource management. The manual also points out the importance of hazard reporting, training, internal safety oversight, and a quality assurance program that includes periodic reviews and updates to maintain regulatory compliance.

Finally, the CYNC SMS Manual states that it must be officially reviewed at least once a year, preferably during the 1st fiscal quarter, in conjunction with the annual management review by the SMS manager. The manual must be amended as necessary to ensure its effectiveness.

At the time of the occurrence, the CYNC SMS Manual had last been updated on 30 August 2018.

1.18.3.4.3 Risk management

Proactive risk management involves actively seeking out potential safety hazards, analyzing, and assessing the associated risks, then putting mitigation measures in place to reduce the level of risk. For each activity, the operator must assess the potential hazards. This may mean conducting risk assessments to identify potential hazards and applying risk management techniques. These risk assessments should be conducted “during the implementation of your SMS and at regular intervals thereafter”Transport Canada, Advisory Circular (AC) 107-001: Guidance on Safety Management Systems Development, Issue No. 01 (01 January 2008), section 6.3.2(a): Assessment Frequency. and “when major operational changes are planned.”Ibid., section 6.3.2(b): Assessment Frequency.

According to information gathered during the investigation, no risk assessments were conducted for some of the circumstances at CYNC. Specifically, there were no assessments of the risks associated with the staff working at the airport, whether it be the high turnover, the presence of an acting manager over an extended period, or the performance of untrained and unsupervised staff.

However, 1 month before the occurrence, a risk assessment of the staff turnover in the Programs Branch at TC and a list of mitigation measures had been submitted to the AE. Some of the mitigation measures, such as training new employees, holding SMS committee meetings, and developing a work plan, had been implemented but had not had the time to have a significant impact at the time of the occurrence.

1.18.3.4.4 Quality assurance program

1. General

TCCA defines quality assurance as follows:

Quality assurance is based on the principle of the continuous improvement cycle. In much the same way that SMS facilitates continuous improvements in safety, quality assurance ensures process control and regulatory compliance through constant verification and upgrading of the system. These objectives are achieved through the application of similar tools: internal and independent audits, strict document controls and on-going monitoring of corrective actions.Ibid., section 9.2(1): PDCA, p. 48.

Section 12 of CYNC’s SMS Manual is dedicated to the airport’s quality assurance program. The purpose of this program is to obtain a systems-based independent evaluation that is focused on the following:

- Determining compliance with regulatory requirements;

- Identifying areas of non-conformance with internal policies and procedures; and

- Identifying opportunities to improve the Airport’s policies, procedures and processes.Transport Canada, Safety Management System Manual – Wemindji Airport, RDIMS No. 5574410-v11 (30 August 2018), section 12.1: Introduction, p. 26.

CYNC’s SMS Manual also states:

When properly implemented, the Quality Assurance Program ensures that procedures are carried out consistently, that problems can be identified and resolved, and that the Airport can continuously review and improve its procedures, and operations.Ibid.

To achieve this goal, the CYNC quality assurance program includes routine safety inspections, operational audits, SMS audits, and site visits. Routine safety inspections are conducted by operational staff daily. Operational audits are carried out on a 3-year cycle, in accordance with the CARs. SMS audits validate compliance with established SMS procedures. Site visits, which occur at least twice a year, are an opportunity for TC staff to conduct an inspection, hold any necessary meetings on site, and meet with airport staff in person, understanding that Indigenous communities prefer these types of interactions.

At CYNC, operational audits and SMS audits are conducted at the same time by the regional SMS manager or an independent third party, if necessary.

The CYNC AE is responsible for:

- Ensuring the implementation, maintenance and proper functioning of the SMS;

- Initiating internal verification audits, in collaboration with the Executive Committee;

- Ensuring available financial and human resources to conduct the audits;

- Approve the implementation of the corrective measures plans following the results of internal audits.Ibid., section 12.4: Responsibilities for Carrying Out the Quality Assurance Program, p. 28.

2. Audits and site visits

According to version 11 of the CYNC SMS Manual, dated August 2018, which had not been revised at the time of the occurrence, operational audits and SMS audits are conducted at the same time, staggered over 3 years: TP 312 facilities the 1st year (2017–2018), manuals the 2nd year (2018–2019), and interviews the 3rd year (2019–2020). The CYNC quality assurance program did not have an audit plan for after 2020.

The last operational audits and SMS audits at CYNC were conducted by an independent third party on behalf of the airport operator from 15 October to 05 November 2018. Several operational items, such as snow removal, the emergency response plan, and the airport SMS, were evaluated. The audits revealed the following findings:

- need to review and update the winter maintenance plan every year before 30 September to prepare for winter;

- recommendation to provide the airport with the necessary equipment to spread the abrasive products required for ice removal;

- suggestion to develop a complete training program for snow removal operations, including written tests to evaluate knowledge, especially for seasonal employees;

- recommendation to provide additional training to staff on the production of AMSCRs;

- recommendation to inspect movement area surfaces daily and issue an AMSCR when conditions change, in accordance with section 2.5.1.3 of TP 312;When the inspections were conducted, the movement area surfaces were covered with a light layer of snow, but no AMSCR had been issued.

- recommendation to record NOTAMs in a log and check their accuracy on the NAV CANADA website;NOTAMs were being issued verbally or sent by fax to the flight service station, but no paper copies were available on site.

- need to keep all training certificates pertaining to the emergency response plan in a specific file at the airport to facilitate tracking;

- recommendation to have the Wemindji Airport emergency coordinator take the necessary training on the emergency plan as soon as possible;

- importance of meeting the deadlines stipulated in the SMS Manual for reviewing occurrence reports and conducting investigations;

- recommendation to record the start and end dates of all steps related to proactive and reactive reports, and ensure that the SMS Manual reflects these changes;

- suggestion to follow up with employees regarding SMS-related reports.

In addition to these operational audits and SMS audits, the quality assurance program includes site visits at least twice a year. These visits, conducted by the TC program officer, include meetings with the airport manager and operational staff, along with safety committee meetings. Each site visit is followed up with a site visit report, which is formally reviewed and updated as necessary after 3 months to ensure the effectiveness of any corrective action put in place.

From 2018 to the date of the occurrence, the following site visits were conducted by the program officer:

- 2018: 3 visits (instead of the required 2), 1 of which was conducted in April to welcome the new airport manager;

- 2019: 1 visit in March for winter, during which the outstanding items from the visits held from 2016 to 2019 were reviewed;

- 2022: 1 visit in November to help the program officer who held the position from April 2021 to November 2022 to become familiar with the airport.

No site visits took place from the one in November 2022 until the date of the occurrence.

3. Corrective action plan

According to the SMS quality assurance program, the program officer must produce a corrective action plan (CAP) based on audit reports. This plan must include a schedule for the proposed corrective actions (immediate, short term, and long term) and must be approved by the AE.

After the operational and SMS audits were conducted at CYNC in 2018, recommendations were made to improve snow removal operations, the emergency response plan, and the SMS. However, no CAP was established to address the issues raised.

At the time of the occurrence, no other audits had been conducted at CYNC since 2018, and there were no site visits in 2020 or 2021, or from November 2022 until the occurrence.

1.18.3.4.5 Safety management system management reviews

According to the CYNC SMS Manual, the SMS manager, in collaboration with the airport manager, must conduct an annual review of the SMS program during the 1st fiscal quarter to ensure that the program is effective and remains that way. The review includes the following:

[…]

- Portrait of the year (number of SMS reports, risk management, risk profile, hazard list)

- Review of SMS Policies (changed if needed)

- Review of goals, objectives and performance indicators (updated if needed) […]

- Risk assessment

- Assessment of the effectiveness of corrective actions

- Examination of internal audit(s) […]

- Measure of employee understanding of their SMS roles and responsibilities

- Assessment of changes that could have an impact on the SMS (update the SMS if needed)

- Organizational or technical changes that may have an impact on the SMS;

- Evaluation of previous management reviews and follow-up measures.Transport Canada, Safety Management System Manual – Wemindji Airport, RDIMS No. 5574410-v11 (30 August 2018), section 6: Management Review, p. 15.

Amendments may be made as needed, and once the management review is completed, the report is sent to the regional SMS officer, who has it approved by the AE.

No management reviews were conducted for fiscal years 2019–2020, 2021–2022, and 2022–2023. The review for 2020–2021 had not been approved by the AE.

1.18.4 Airport regulatory surveillance by Transport Canada Civil Aviation

1.18.4.1 General

Regulatory surveillance is TCCA’s main tool for verifying whether a Canadian aviation document holder is complying with regulatory requirements. TCCA oversight has evolved since SMSs were first put in place: in addition to traditional regulatory oversight, it includes a series of activities intended to verify whether Canadian aviation document holders have effective systems that enable them to comply with regulatory requirements and manage risks proactively.

TCCA conducts systems-level surveillance (assessments and program validation inspections [PVIs]) and process-level surveillance (process inspections [PIs]), targeted inspections, and compliance inspectionsTransport Canada, Staff Instruction (SI) SUR-001: Surveillance Procedures, Issue No. 09 (04 August 2020), section 5.0: Surveillance activities, pp. 16–17. to provide oversight in a way that promotes effective safety management, while enabling intervention as necessary to ensure that there is at least a minimum degree of compliance with regulations.

When the CARs require an SMS, as is the case for airports in Canada, TCCA has a responsibility to evaluate and validate the SMS. Furthermore, it is these SMSs that are the primary focus of surveillance activities, especially assessments, which are intended to assess the effectiveness of an operator’s systems and the degree of compliance with the CARs.

PVIs are used to review one or more elements of an SMS or any of the operator’s other regulated areas using sampling methods to check if the operator can meet regulatory requirements on an ongoing basis.

PIs are inspections that focus on one or more specific processes. They verify whether the processes are accomplishing their objectives and meeting regulatory requirements.

Targeted inspections are flexible surveillance activities that combine compliance monitoring with information gathering to gain an understanding of a certain topic or issue.

Compliance inspections are designed to check that a product or activity meets applicable regulatory requirements or standards. The frequency of these various types of periodic inspections depends on factors such as the type of operations, turnover of key staff in the enterprise, its compliance history, and the nature of the findings identified during previous surveillance activities.

If, during their various surveillance activities, TCCA inspectors identify deficiencies or non-compliances with regulatory requirements, they make findings, which are factual accounts based on evidence of non-compliance with the CARs requirements. All findings of non-compliance to a rule of conductIn Transport Canada, Staff Instruction (SI) SUR-029: Addressing Deficiencies Identified Through Surveillance, Issue No. 03 (03 May 2023), section 2.3: Definitions and abbreviations, p. 6, TCCA defines a rule of conduct as “a provision which requires or prohibits a particular conduct or behaviour.” require corrective action by the enterprise, which must submit a CAP to TCCA within 30 days.

A CAP describes how the enterprise plans to resolve the regulatory non-compliance and ensure ongoing compliance in the future. The CAP must include the following elements:

- factual review of the finding;

- root-cause analysis;

- proposed corrective actions (short term and long term);

- implementation timelines; and

- managerial approval.

TCCA acknowledges receipt of the CAP. The inspector evaluates the CAP to determine if it adequately addresses the non-compliances and if the processes used to develop the CAP are appropriate given the organization’s size and complexity.

After the CAP has been presented, it is up to TCCA to check if the short-term corrective actions have been implemented and have resolved the identified non-compliances. To assess the effectiveness of long-term corrective actions, TCCA will include all areas of non-compliance in the scope of the next planned surveillance activity.

If all short-term corrective actions have been completed and have brought the operator back into compliance with regulatory requirements, results have been recorded, and no further action is necessary, the convening authorityTransport Canada, Staff Instruction (SI) SUR-001: Surveillance Procedures, Issue No. 09 (04 August 2020), section 2.3: Definitions and abbreviations, p. 6, indicates that the convening authority is “the individual that oversees and is accountable for the conduct of a surveillance activity”. may close the file.

When the corrective actions have not been implemented or are not effective, TCCA must take the appropriate action, which may include:

(i) A request that the enterprise produce another CAP or revise the current one;

(ii) A provision for further time for the enterprise to implement corrective action;

(iii) Enforcement action;

(iv) Certificate action.Ibid., section 12.16(3): Not Completed (Short Term and Long Term), p. 42.

These actions are determined on a case-by-case basis by the TCCA convening authority, who must “document the decision to take action and the process used to arrive at said action.”Ibid., section 12.16(4), p. 42.

1.18.4.2 Transport Canada Civil Aviation surveillance of Wemindji Airport

1.18.4.2.1 Assessment of safety management system implementation

The gradual implementation of SMSs recommended by TCCA can be broken down into 4 phases, with the last one being the final confirmation that the SMS complies with the CARs and that the operator can maintain this compliance.

On 14 June 2016, TCCA completed its assessment of CYNC’s SMS. This assessment, which covered the period from 12 June 2011 to 12 June 2016, addressed all components of the SMS and compliance with the relevant standards set out in TP 312. The assessment report, published 8 months later, in March 2017, contained a total of 15 findings of non-compliance, 11 of which were moderate,The Rapport d’évaluation - 14 juin 2016 - Aéroport de Wemindji produced by Transport Canada, Quebec Region, 5151-Q554, p. 11 indicates that [translation]: “A finding is considered moderate where a surveillance activity has identified that the area under surveillance has not been fully maintained and examples of non-compliance indicate that it is not fully effective; however, the enterprise has clearly demonstrated the ability to carry out the activity and a simple modification to their process is likely to correct the issue”. and 4 of which were major,The same document goes on to indicate on p. 11 that [translation]: “A finding is considered major where a surveillance activity has identified that the area under surveillance has not been established, maintained and adhered to or is not effective, and a system-wide failure is evident. A major finding will typically require more rigorous and lengthy corrective action than a minor or moderate finding”.,TCCA stopped classifying non-compliances with the publication of SI SUR-001 Issue No. 09 in June 2019 and of SI SUR-029 Issue No. 02 in October 2019. and the 6 elements of CYNC’s SMS were deemed non-compliant with regulatory requirements.

A CAP was presented to TCCA on 23 June 2017. The short-term corrective actions for the majority of the 15 findings pertained to staff training and adherence to procedures. Overall, the root-cause analysis highlighted that insufficient time, resources, and budget were the main reasons for the deficiencies in staff training. The long-term corrective actions were related to quality assurance processes, including manual revisions and management reviews.

The corrective actions for 3 of the moderate findings were accepted in September 2017. The proposed actions to address the other 8 moderate findings and the 4 major findings were rejected. A new version of the CAP was presented to TCCA at the end of February 2018. All the proposed actions were accepted on 29 March 2018.

The surveillance activities carried out for the evaluation of CYNC’s SMS were completed on 20 January 2020. Notes on file mentioned that there were still several deficiencies (e.g., quality assurance program generally not being followed and the absence of procedure for updating manuals). The notes on file also indicated that the enterprise had stated its willingness to put measures in place to achieve positive performance goals.

1.18.4.2.2 Compliance inspection

On 29 October 2019, TCCA carried out a compliance inspection at CYNC and met with the acting airport manager. In its report, TCCA made comments on some of the physical characteristics and facilities and noted that staff training was up to date, the SMS process was working well, and communications with the TC SMS manager were deemed to be effective.

1.18.4.2.3 Targeted inspections

During the COVID-19 pandemic, TCCA did not conduct any site visits to CYNC, but it did produce 2 status reports for the airport based on information obtained remotely. TCCA noted items pertaining to operations and the continuation of air services during the pandemic.

According to the report dated 21 April 2020, the certificate holder’s operations had continued as normal, with no changes to the structure or key staff, despite the reduction in the number of flights.

The report dated 15 June 2021 further states that runway maintenance was being performed as normal to ensure safety. MEDEVAC flights were continuing as needed, and no employees had been laid off. The SMS was continuing to be managed, and no organizational changes had been made that might affect airport operations. Despite the drop in revenue associated with the lower landing fees collected by CYNC, the airport did not experience financial pressures.

1.18.4.2.4 Process inspection in 2023

Approximately 2 months before the occurrence, TCCA conducted a PI of CYNC’s quality assurance program. The PI, which took place from 11 to 15 September 2023, revealed the following issues with safety planning and management [translation]:Transport Canada, Feuille de travail pour l’inspection de processus, Aéroport de Wemindji, RDIMS No. 19587160.

- Internal audit planning: Only the 2018–2019 management review was available.Ibid., p. 6. The management reviews for 2019–2020 and 2021–2022 were missing and the review for 2020–2021, completed in January 2022, was not signed by the AE.

- Internal audit process: The airport operator did not demonstrate that it was communicating findings to the AE and, where applicable, whether the findings were being communicated in accordance with the documented process.Ibid., p. 16.

- Corrective action process: The airport operator was not implementing corrective action in response to findings arising from the quality assurance program.Ibid., p. 18.

- Management and control: The airport operator was not ensuring that the SMS manager was performing his duties with respect to quality assurance and, where applicable, whether these duties were being performed in accordance with the documented process.Ibid., p. 28.

On 29 November 2023, following this PI, a finding of non-compliance was issued with respect to the rule of conduct set out in section 302.504(c) of the CARs because the airport certificate holder was not fulfilling its obligation to ensure that the SMS manager was performing the duties required under section 302.505 of the CARs.

TCCA records for CYNC did not contain any documents pertaining to enforcement or certificate action from 2010 to 2024.

1.18.5 TSB recommendations regarding safety management systems and regulatory oversight

TSB Air Transportation Safety Investigation Report A13H0001,TSB Air Transportation Safety Investigation Report A13H0001, at https://www.tsb.gc.ca/eng/enquetes-investigations/aviation/2013/a13h0001/a13h0001.html (last accessed on 07 January 2026). which examined an Ornge air ambulance accident that occurred in 2013 at Moosonee, Ontario, revealed that operators with an SMS do not all have the same capability and willingness to manage risks effectively. Therefore, the regulator must be able to vary the type, frequency, and focus of its surveillance activities to provide effective oversight to operators that are unwilling or unable to meet regulatory requirements or effectively manage risk. Further, the regulator must be able to take appropriate enforcement action in these cases.

In investigation A13H0001, the TSB noted that TC’s approach to surveillance activities did not lead to the timely rectification of the non-compliance.

Consequently, the Board recommended that

the Department of Transport conduct regular SMS assessments to evaluate the capability of operators to effectively manage safety.

TSB Recommendation A16-13TSB Recommendation A16-13: Oversight of commercial aviation in Canada: SMS assessments (issued 15 June 2016), accessible at https://www.tsb.gc.ca/eng/recommandations-recommendations/aviation/2016/rec-a1613.html (last accessed on 07 January 2026).

Furthermore, investigations have shown that where operators have been unable or unwilling to address safety deficiencies, TC has had difficulty adapting its approach to ensure that deficiencies are effectively identified and addressed quickly.

Therefore, to ensure that operators use their SMS effectively, and to ensure that they continue operating in compliance with regulations, the Board also recommended that

the Department of Transport enhance its oversight policies, procedures, and training to ensure the frequency and focus of surveillance, as well as post-surveillance oversight activities, including enforcement, are commensurate with the capability of the operator to effectively manage risk.

TSB Recommendation A16-14TSB Recommendation A16-14: Oversight of commercial aviation in Canada: policies, procedures and training (issued 15 June 2016), accessible at https://www.tsb.gc.ca/eng/recommandations-recommendations/aviation/2016/rec-a1614.html (last accessed on 07 January 2026).

Since then, the TSB has followed up with TC regarding the actions taken to address these 2 recommendations. TC responded to each recommendation by indicating the concrete actions that had been taken or that were going to be taken, and the TSB assessed these responses. At the time of publication of this report, TC’s most recent responses to these 2 recommendations were received in September 2024. The TSB assessed TC’s responses as unsatisfactory. The TSB’s assessment of these responses, as well as previous responses and assessments, can be found on the TSB website.Air transportation safety recommendations, at https://www.tsb.gc.ca/eng/recommandations-recommendations/aviation/index.html (last accessed on 07 January 2026).

1.18.6 TSB Watchlist

The TSB Watchlist identifies the key safety issues that need to be addressed to make Canada’s transportation system even safer.

Safety management and regulatory surveillance are Watchlist issues.

The TSB has repeatedly highlighted the advantages of having an SMS. As this occurrence has shown, simply having an SMS does not guarantee an appropriate safety level. An SMS must be effective so that hazards and their associated risks can be managed through the necessary mitigation measures.

ACTION REQUIRED The issue of safety management in air transportation will remain on the Watchlist until

|

Adopting an effective SMS is only part of the equation. Effective regulatory surveillance is also necessary. As this occurrence has shown, if appropriate action is not taken in response to non-compliances identified through surveillance activities, the non-compliances will not be rectified.

ACTION REQUIRED The issue of regulatory surveillance in air transportation will remain on the Watchlist until TC demonstrates that its surveillance framework can:

Successfully addressing TSB Recommendation A16-14 is key to achieving these objectives. |

2.0 Analysis

The investigation did not reveal any defects that may have prevented the occurrence aircraft from functioning normally. The flight crew members held the appropriate licences and ratings in accordance with regulations and there was no indication that their performance was degraded by physiological factors such as fatigue.

To better understand why this occurrence happened, the analysis will begin by focusing on snow removal operations at Wemindji Airport (CYNC), followed by pilot decision making during the approach and landing. It will then examine safety and risk management at CYNC, and end with Transport Canada Civil Aviation (TCCA) regulatory surveillance.

2.1 Snow removal operations at Wemindji Airport

Given that snow had accumulated on the CYNC runway during the night of 02 to 03 November, the vehicle operator on duty began removing snow from the runway upon arrival at the airport on the morning of 03 November. The snow was removed from the runway in an asymmetrical manner, over a width of approximately 65 feet, leaving 2 snow windrows, each about 18 inches high, with one 23 feet from the southern edge and the other 12 feet from the northern edge.

The CYNC airport operations manual (AOM) states that a facilities inspection must be conducted every day, including movement areas and winter maintenance. Furthermore, the CYNC AOM and winter maintenance plan state that aircraft movement surface condition reports (AMSCRs) must be produced at least twice a day during the entire winter. The winter maintenance plan specifies that these reports must be produced in the morning and at the end of the day.

The vehicle operator, who had begun his job a few days before the occurrence, had not yet received training on the winter maintenance plan or the snow removal procedures specific to the airport. Not knowing that the runway needed to be cleared across its entire width, he felt that a wide enough path had been cleared and began doing other tasks that needed attending, given that he was the only employee working at the airport that day.

Airport logs indicate that a facilities inspection was conducted the morning of 03 November, with nothing out of the ordinary noted or reported in the runway surface condition NOTAM (RSC NOTAM).

The successful landing of 2 flights during the day may have validated the vehicle operator’s belief that enough snow had been removed, which may explain why he prioritized other tasks and did not note or report any deficiencies concerning the runway condition in the RSC NOTAM.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

The vehicle operator found himself completing tasks and making decisions for which he had not been trained and did not have the necessary experience or knowledge. He therefore partially removed the snow from the runway, leaving snow windrows that reduced the width asymmetrically along the entire length of the runway, and did not mention the windrows in the information to be included in the RSC NOTAM.

Training snow removal staff is crucial, but supervising snow removal operations is also a control mechanism that is essential for priority management and workload distribution, reinforcing adherence to snow removal procedures, and ensuring that risks are managed effectively. Proper supervision provides independent validation of decisions made by staff and assessment of the associated risks and ensures that tasks are performed correctly and completely in the interest of safety. Having qualified supervisors who have received specific training in managing risks associated with snow removal operations is indispensable to guarantee effective and independent monitoring of operations. On the day of the occurrence, the airport manager was absent, and no qualified staff was at the airport to supervise the vehicle operator.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

Because snow removal activities were not being supervised on the day of the occurrence, the runway remained partially clear without any mention in the RSC NOTAM, and the hazardous situation was not identified or corrected.

2.2 Pilot decision making during the approach and landing

The RSC NOTAM in effect at the time of landing indicated a mix of compacted snow and gravel over 80% of the runway width, and 1/8 inch of wet snow over the remaining 20%. Given that the RSC NOTAM did not indicate that the runway width had been reduced or that there were snow windrows on the runway, it was understood that the entire width of the runway had been cleared.

Approximately 30 minutes before the arrival of the 1st Propair Inc. (Propair) medical evacuation (MEDEVAC) flight (PRO4200M), the company’s dispatch spoke with CYNC’s snow removal vehicle operator to inform him of the arrival of the 2 flights. During this call, there was no mention that the runway width was reduced. The pilot of flight PRO4200M landed on Runway 28 without incident and contacted the pilot of the occurrence flight (PRO4215M), which was following PRO4200M, to provide a weather report. However, the pilot made no mention of snow windrows on the runway.

The occurrence aircraft’s approach phase was conducted in accordance with the criteria set out in the company’s standard operating procedures (SOPs) and the pilot’s operating manual (POM). Although the aircraft touched down slightly to the left of the centreline, it was within the lateral boundaries of the runway. Still, the left main landing gear and propeller struck a snow windrow that was on the runway, 23 feet from the edge. The aircraft then swerved and exited the runway, coming to rest approximately 45 feet from the runway edge.

Situational awareness requires extracting information and integrating it with one’s knowledge to create a mental model of the situation and predict future events. If pilots have accurate information on actual runway conditions, they can create a mental model that reflects reality and adjust their manoeuvres to conduct a safe landing. Given that the occurrence aircraft’s flight crew had not been informed of the snow windrows on the runway, they were not able to create a mental model that reflected reality or prepare accordingly.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

With no mention of the reduced runway width or of the snow windrows in the RSC NOTAM, the flight crew had created the mental model of an unencumbered runway, which may have been reinforced by the previous flight’s normal landing. The flight crew was therefore unable to take appropriate action in response to the actual runway conditions.

During the landing, the aircraft touched down slightly to the left of the centreline and the left main landing gear and propeller struck a snow windrow that was on the runway 23 feet from the edge. The aircraft then swerved and exited the runway. It came to rest approximately 45 feet from the edge of the runway.

The snow windrows on the runway were also not perceived as a hazard that needed to be reported by the pilots who used the runway on the day of the occurrence and the day before, even though they considered the situation to be unusual.

Finding as to risk