Grounding

loaded bulk carrier "CSL ATLAS"

Lower Cove

St. George's Bay, Newfoundland

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

The "CSL ATLAS" departed from Lower Cove, Newfoundland, bound for New York, U.S.A. The master did not engage the services of a pilot for the departure. Shortly after, the vessel grounded 1.1 cables west of Pigeon Head. The "CSL ATLAS" jettisoned 5,645 tonnes of cargo and was refloated later the same day. The vessel sustained extensive damage to the underside portion of the hull; three compartments were holed. There was neither pollution nor injury as a result of this grounding.

The Board determined that the "CSL ATLAS" grounded because the master sailed at night from a port with which he was unfamiliar, did not employ the recognized departure procedure, did not establish either a bridge resource management regime or a voyage plan for leaving the berth, and did not engage either the pilot or tug available.

1.0 Factual Information

1.1 Particulars of the Vessel

| "CSL ATLAS" | |

| Official Number | 71599 |

| Port of Registry | Nassau, Bahamas |

| Flag | Bahamian |

| Type | Self-unloading bulk carrier |

| Gross Tons Footnote 1 | 41,173 |

| Cargo | 57,289 tonnes of limestone pellets |

| Length | 227.40 m |

| Breadth | |

| 32.05 m | Draught F Footnote 2: 12.00 m (at departure) A: 12.25 m |

| Built | 1990, Verolme, Brazil |

| Propulsion | One two-stroke, six-cylinder Sulzer diesel engine rated 11,995 kW, driving a single fixed-pitch right- handed propeller - Bow thruster fitted |

| Owners | CSL International Beverly, Massachusetts, U.S.A. |

1.1.1 Description of the Vessel

The "CSL ATLAS" has five holds beneath which are double-bottom tanks. The bow thruster compartment and the forward peak tank are forward of the collision bulkhead and extend from the main deck to the bottom of the shell plating. The...

1 Units of measurement in this report conform to International Maritime Organization (IMO) standards or, where there is no such standard, are expressed in the International System (SI) of units.

2 See Glossary for all abbreviations and acronyms.

3 All times are NST (Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) minus 3½ hours) unless otherwise stated.

...navigation bridge, crew accommodation and engine-room are all located aft (see photographs - Appendix A).

1.2 History of the Voyage

The sequence of events is derived from interviews of the ship's personnel. It does not correlate in all respects with other physical evidence.

The "CSL ATLAS" arrived at Lower Cove, Newfoundland, at 1448 Footnote 3, on 16 December 1993. A pilot, employed by the mining company, assisted in berthing the vessel. The master and the pilot decided to berth the vessel port side to the wharf because of the strong northerly winds.

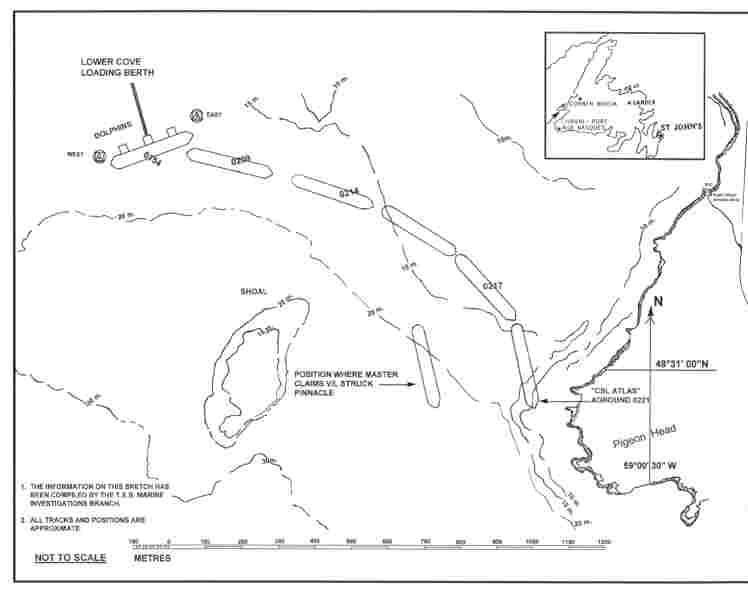

Upon completion of loading, the vessel departed from Lower Cove at 0154, 18 December, bound for New York, U.S.A. (see sketch of area - Appendix B). The master, who had not requested the services of a pilot, had the conduct of the vessel. On the bridge with the master were the officer of the watch (OOW) and a helmsman. The chief officer and one cadet were stationed forward, and the second officer and one cadet were stationed aft.

Because of the absence of any visual aids, navigation was by radar alone, conducted solely by the master. A system of parallel-indexing was used. The echo-sounder had been turned on and set for digital read-out, with the low-depth underkeel clearance (UKC) alarm set at 3 m.

The OOW was responsible for operating the engine and bow thruster controls, as ordered by the master, for entering the engine movements into the bell book, and for monitoring the rudder indicator.

After all the moorings had been let go, the deck lights remained lit as the crew secured for sea. A look-out was not posted on the forecastle where visibility was not affected by the lights.

Over the next half-hour, various courses were steered and various engine movements, from "dead slow ahead" to "full ahead", were executed.

Initially, port helm was applied to bring the stern clear of the dolphins and the bow thruster used to starboard to bring the ship's head around. The master then ordered a course of 105° True (T) as the stern of the vessel became aligned with the eastern dolphin.

At 0217, with the vessel moving ahead at an estimated speed of between two and three knots, the bow thruster and the helm were set to swing the vessel hard-to-starboard to alter course to 168°(T). Soon after, the engine was ordered to "full ahead".

At this time, the distance from the nearest land echo was reported to have been two cables. However, at 0221, the vessel struck bottom on the forward starboard side and then heeled to port. The engine was put to full astern and, at 0227, the engine control was transferred to the engine-room and maximum revolutions applied.

At 0230, all power aboard the vessel was lost and was not restored until 0255. During this period, the "CSL ATLAS" was reported to have drifted inshore, coming to rest heading 167°(T) in a position 254°(T), 1.3 cables from Pig Point, Pigeon Head.

Internal soundings established that the vessel was holed in the forepeak tank, the bow thruster compartment and the No. 1 double-bottom tank. When power was restored, pumping of the forepeak and No. 1 double-bottom tanks commenced and remained ongoing.

Between 1245 and 1340, unsuccessful attempts were made to refloat the vessel by using her own main engines and with the assistance of the small Canadian tug "POINT VIKING". Further unsuccessful attempts were made between 1504 and 1640 with the CCGS "J.E. BERNIER" also assisting. During the latter efforts, the vessel slewed slightly, coming to rest heading 145°(T).

At 1530, gale force winds were forecast by Environment Canada for the area in which the "CSL ATLAS" was stranded. Because the vessel was in a vulnerable position, the master requested permission to jettison a portion of the cargo to lighten and refloat the vessel. Approval was obtained from the Canadian Coast Guard (CCG), Environment Canada officials and the vessel's owners. Using her own discharging equipment, the vessel commenced jettisoning cargo from the No. 1 hold at 1800.

The "CSL ATLAS" was afloat at 2256 and, under the conduct of a pilot, proceeded to a safe anchorage in St. George's Bay. After receiving a damage report from divers, the vessel was issued an Interim Certificate of Class, allowing her to proceed to her destination and thence to dry-dock for permanent repairs.

1.3 Injuries to Persons

None of the 32 persons on board were injured.

1.4 Damage to the Vessel

Extensive damage was sustained by the forward bottom shell plating. In addition to the three holed compartments, the plating was severely rippled from the centre line to the turn of the bilge, and the forefoot was set up extensively. The damage ran in a fore-and-aft line, on either side of the keel, from the stem to the collision bulkhead.

1.4.1 Environmental Damage

Approximately 5,645 tonnes of limestone pellets, jettisoned during refloating attempts, were discharged into the water, 60 m inshore of the grounded vessel.

1.5 Certification

1.5.1 Vessel

The vessel was certificated, manned and equipped in accordance with existing regulations.

1.5.2 Personnel

Both the master and the OOW held qualifications appropriate for the class of vessel on which they were serving and for the voyage being undertaken.

1.6 Personnel History

1.6.1 Master

The master had served in this capacity since 1984 and had been master of the "CSL ATLAS" for one and a half years. This was his first visit to Lower Cove, although he had conned his vessel in and out of various other isolated ports. He had completed a course on the operation of radar with Automatic Radar Plotting Aid (ARPA) in November 1991.

The master preferred to be on board during cargo operations but not necessarily involved in them. The evening before departure, he retired at 1900 and was awakened at 0100, 18 December. At the time of stand-by, he was absolutely rested.

1.6.2 Officer of the Watch

The additional second officer had sailed in this capacity for two years and aboard the "CSL ATLAS" for three months. He had not previously been to Lower Cove.

During cargo operations, he was on deck from 0600 to 1200 and from 1800 to 2400. He did not consider himself tired at the time of departure, although he had slept only four hours the previous afternoon.

1.7 Environmental Information

1.7.1 Weather

Before and at the time of the occurrence, the sky was partly cloudy and the visibility, where it was not restricted by the deck working lights, was good. It was dark. There was no appreciable wind.

1.7.2 Tidal Current

There was no significant current which may have adversely affected the vessel. High water was at 0210.

1.8 Navigation Equipment

1.8.1 Vessel

There was a full range of navigation equipment on board, adequate for the safe operation of the vessel. At the time of the occurrence, the relevant instruments in use were:

- two Sperry 340 marine radars, each equipped with a Plan Position Indicator (PPI) display. One set is equipped with an ARPA;

- a gyrocompass repeater at the steering position;

- an echo-sounder equipped with paper trace, digital read-out capabilities and an adjustable minimum-depth alarm; and

- a course recorder.

The ARPA radar was equipped with features which provide sophisticated technology to support navigation safety. The echo-sounder was reported to have been in operation during departure, set for digital read-out. The minimum-depth alarm had been set at 3 m (depth under the keel), but no alarm was heard at any time.

A British Admiralty chart of St. George's Bay was on board, but was insufficiently detailed to be of use for entry/departure in the Lower Cove area. Before departure, the ship's agent gave the master Canadian Hydrographic Service survey field sheets Nos. 1000902 and 1000903 which cover the entire Lower Cove area.

When the field sheets on board were examined after the occurrence, there were no tracks which would indicate the planned courses out of the cove nor was there evidence of erasures. The position of the grounding had not been plotted.

1.8.2 Shore

There are no shore navigational aids (navaids) in the Lower Cove area during the winter season. Between June and November, an "isolated danger" buoy is located approximately 3.5 cables south of the Lower Cove berth, indicating the presence of a shoal. This buoy was removed on 23 November 1993, as scheduled, and before the onset of ice.

The berth itself remains lit at night and, in addition to the five dolphins, there are prominent points of land which would provide good radar echoes to the proficient observer.

1.8.3 Publications

The only publication on board with any reference to Lower Cove was the British Admiralty's "Newfoundland Pilot".

1.9 Radio Communications

The master advised the local agent and the Coast Guard Radio Station (CGRS) at Stephenville of the grounding at 0609 and 0649 respectively, by very high frequency radiotelephone. At no time was a MAYDAY declared or an URGENCY situation broadcast. A request for tug and pilot assistance was made by the master through the local agent following the grounding.

1.10 Documentation

The master's account of the grounding appears in abbreviated form in the deck logbook and the master's report.

1.11 Vessel Stability

The vessel had adequate stability at all times.

1.12 Voyage Planning

Although a voyage plan for the passage from Lower Cove to New York had been compiled and approved by the master, it excluded any port plan for either origin or destination. Not familiar with the Lower Cove area, the master had sought and received advice from the agent, who was also a master mariner and tugmaster, on the movements of the vessel from the berth to enable her to clear the shoal area to the south.

This information was not shared with the navigation officers nor were courses marked on the field sheets, then on board.

1.13 Machinery

There was no breakdown or malfunction of the main engine or machinery of the "CSL ATLAS" before the grounding.

1.14 Electrical System

The vessel is equipped with three ship service generators located in the machinery space and one emergency generator located on the boat deck.

When water flooded the bow thruster compartment, there was a current surge in excess of 3,000 amps which caused the breakers of the ship service generator to trip. The bow thruster circuit breaker did not trip. A complete black-out resulted. At this stage, the emergency generator should have cut in and restored limited power, but it did not. The electrician went to the emergency generator room and discovered that the manual/automatic start control switch was in the manual mode. No one could explain why this was the case. Once this control was switched to the automatic mode, the emergency generator started and power was restored to the emergency circuits.

While the vessel was undergoing repairs, it was discovered that the bow thruster breaker had a trip delay exceeding that of the generator breakers. Apparently, this had been the case since the vessel was built but it had gone undetected until this occurrence. It has since been rectified.

1.15 Description of the Approaches to Lower Cove

Lower Cove is exposed to southerly winds. Once a large vessel is inside the cove, there is relatively little room to manoeuvre.

The berth lies in a north-east/south-west direction and consists of five dolphins, spaced approximately 52 m apart, extending 282 m from east to west. Vessels usually pass two cables west of Pigeon Head and berth starboard side to. This approach ensures that the masters of fully laden vessels can take the recognized direct departure route to the south-west. It also facilitates a direct departure from the berth in the event of bad weather.

The distance from the berth to the north-west corner of Pig Point is 1,220 m, from the berth to a shoal area, 580 m, and the width of the channel between the shoal and Pig Point is 808 m.

Fifteen-metre water-depth contours lie 457 m to the south-east and 510 m to the south.

Pilotage for the area is non-compulsory but is readily available as is a small tug for assistance in manoeuvring.

Because of his unfamiliarity with the Lower Cove area, the master had been previously instructed by the vessel's managers to engage the services of a pilot for both arrival and departure.

In addition, the master had been advised that a tug was available. However, the master decided to take the full responsibility of the departure of his vessel.

1.16 Position of Grounding

The master maintained that the "CSL ATLAS" had struck a pinnacle at a distance of two cables (366 m) from Pigeon Head, had heeled to port and then slid off the obstruction. He further maintained that the vessel had then drifted ashore, fetching up 1.3 cables (238 m) from Pigeon Head at 0700.

The master made a radiotelephone call to the local agent at 0309 stating that the vessel was aground 1.1 cables (201 m) from Pigeon Head.

A confirmed position of the vessel when aground was not recorded by the ship's personnel. However, the pilot, who boarded the vessel to assist after the grounding, determined by radar that the vessel was 1.1 cables (201 m) from Pig Point. She was heading 145°(T) and the bow was estimated to be 90 m from the shore. The approximate coordinates were:

Latitude 48°31′02″N

Longitude 059°00′46″W

1.17 Underwater Inspection

An underwater video survey of the vessel showed that she was hard aground across the beam from the bow to the mid-section of the No. 1 double-bottom tank. The forefoot was lifted extensively, the crew in the bow area felt the vessel lift as she made initial contact and heard the sound of tearing metal. The grounding was not felt in the engine-room.

1.18 Confirmation of Water Depth

A detailed hydrographic survey of Lower Cove was completed in May 1993. Field sheets were compiled and completed by the Canadian Hydrographic Service (Atlantic) at the Bedford Institute of Oceanography and were published in October 1993.

Following the master's report that the vessel had struck an uncharted pinnacle, the CCG Newfoundland Region made a vessel available to make two sounding sweeps of the area off Pigeon Head to confirm the depth of water.

At 2034, 24 January 1994, the height of tide was maximum at 0.88 m above chart datum and, with the CCGS "J.E. BERNIER" in a position two cables west of Pigeon Head, the depth of water was recorded as 24 m.

A similar pass was made at low water, which occurred at 0242, 25 January, at which time the depth of water was 0.3 m above chart datum. The depth of water was recorded as 23 m.

No trace of the reported pinnacle was found.

2.0 Analysis

2.1 Introduction

The navigation officers had not been made aware of the proposed manoeuvres for departure. The master adopted an independent command role and there was no discussion of how the departure from the berth was to be accomplished. Without the back-up, monitoring and support of a senior experienced officer and some division of responsibility, the chances of a successful departure were reduced.

The conclusions of the analysis of the physical evidence do not support the version of the sequence of events obtained from interviews with the ship's personnel.

2.2 Damage to the Vessel

An underwater video survey of the damage sustained by the vessel showed that all the damage appeared to run in a fore-and-aft line, on either side of the keel, from the stem to the collision bulkhead.

The forefoot was lifted extensively and the damage ran in a fore-and-aft direction, indicating that the damage resulted from a high impact grounding from directly ahead while the vessel was moving ahead.

The type and extent of the damage incurred by the vessel does not support the master's testimony that the vessel struck a pinnacle while moving ahead, drifted ashore and grounded laterally.

2.3 Reported Underwater Obstruction

Because the master indicated that there was an uncharted pinnacle in the area of the grounding position, sweeps of the area were carried out. No obstruction was found. Given that the sweeps carried out by the CCG were directed to the reported position of the obstruction and that the area had been surveyed by the Canadian Hydrographic Service in May 1993, it is unlikely that such an obstruction exists.

Further, an examination of the video film of the sea bottom and the kelp in the area where the vessel was hard aground did not indicate that the vessel had drifted laterally to her grounded position.

The vessel's echo-sounder trace paper was examined but there was no evidence of a trace. The report that the digital depth read-out was in operation at the time of the grounding cannot be verified. It is not known why the depth alarm did not sound if it was set as reported.

2.4 Decision to Sail at Night

As he had obtained information from knowledgeable persons to assist him in leaving the berth, the master believed that he did not require to engage a pilot for departure, contrary to what he had been instructed to do.

It is evident that the master's local knowledge in the unfamiliar port was insufficient to sail at night. He was under no pressure to do so. The chances of an unassisted successful departure would have been increased by waiting for daylight.

2.5 Reconstruction of the Departure

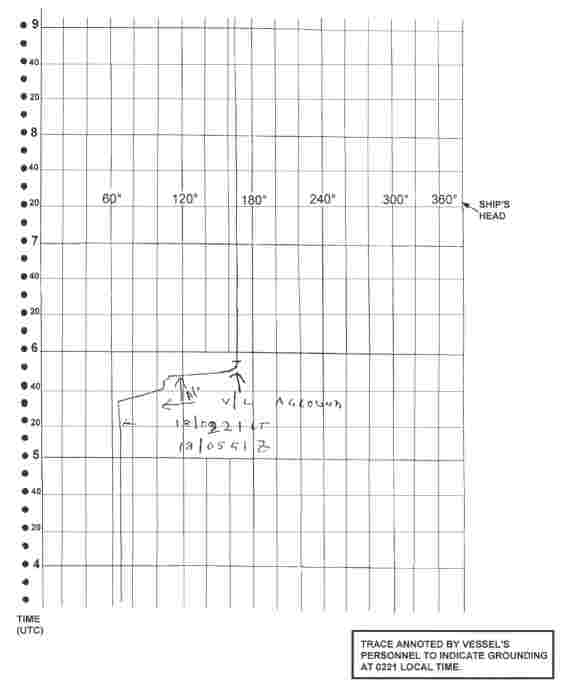

By referring to the engine movements as recorded in the bell book, to the course-recorder trace and to the vessel's manoeuvring data (this information is tabulated in Appendix C), it was possible to reconstruct the approximate movements of the vessel from the berth to the grounding position.

It can be seen from the sketch of the area (see Appendix B) that, at about 0215, the vessel crossed the 15 m contour when vibration was felt. The vessel would have had an UKC of less than 1 m when making the starboard swing to clear Pig Point with engines at "full ahead".

In the shallow water, the vessel's manoeuvrability would have been hampered by squat. As the speed over the ground increased, the vessel's squat would have decreased the UKC and the swing to starboard would have become more laboured due to these hydrodynamic effects. This would also have increased the vessel's advance and transfer, and decreased her turning efficiency.

It is likely that the master became aware of this situation because speed was reduced at 0216. Attempts were made to tighten the vessel's turning circle by the use of the bow thruster at 0217, but the vessel was, at this time, moving ahead at a speed of two to three knots, and the effect of the bow thruster would have been minimal. The engines were not put astern to reduce speed and squat, and to increase bow thruster efficiency. In fact, the engines were not put astern until after the grounding.

Speed was again increased to "full ahead" at 0218 and at 0220, immediately before the vessel went aground. Between these times, however, the vessel's UKC and manoeuvrability were further decreasing in the rapidly shoaling water.

Given the manoeuvres carried out from the time that the vessel crossed the 15 m contour, the vessel's grounding was inevitable.

2.6 Departure Procedure

Given that the vessel had been berthed port side to the dock and considering the physical limitations of the cove, two alternate departure strategies were available to the master. One alternative was to swing the vessel "short-round" off the berth and proceed out of the bay on the south-westerly heading which would be taken by a vessel which had been conventionally secured starboard side to the dock. The second, which the master elected to attempt, was to take the vessel on a southerly heading between the shoal and Pigeon Head, after making a tight turn to starboard immediately on clearing the berth. Either method is feasible if the hazards inherent in the procedure are recognized.

There was adequate water depth near the berth for either manoeuvre to be carried out, and the required turn can be initiated by the use of the vessel's moorings, with or without the assistance of a tug. Once the vessel's bow or stern has cleared the dock, a swing can be induced by alternating the main engine ahead and astern while applying the appropriate helm. The bow thruster can also be used to maximum advantage to assist when the vessel is not making way through the water. The first manoeuvre required that the vessel swing through 180° and the second that the vessel swing through some 90°.

In the present case, the system of parallel indexing employed by the master did not alert him to the fact that the vessel had made too much headway before completing the required 90° change in heading. To be effective, the parallel indexing technique must incorporate a means of monitoring the vessel's progress. Also, in this instance, the capability of the ARPA to provide sophisticated navigational support was not used to supplement the system of parallel indexing employed.

2.7 Visibility from the Bridge

After all the mooring lines had been let go, the crew members were engaged in "clewing up" for sea which necessitated the use of the deck working lights. Although it was deemed necessary for this operation, the deck lighting was detrimental to visibility from the bridge.

Visibility from the bridge was not reported to have been a factor. People on the bridge would not have been able to obtain full night vision. This would also have caused a reduction in situational awareness and of how the vessel was responding to the master's manoeuvres.

Because no look-out was posted on the forecastle head, clear of the deck lighting, there was no possibility of an early warning that the vessel was closing on the land.

3.0 Findings

- The master decided to sail at night from a port with which he was unfamiliar.

- The master did not engage the services of either the pilot or the tug available to assist him.

- The vessel was not turned short-round in the area of the berth to enable her to follow the recognized departure procedure.

- The master's departure plan was known only to him; he did not discuss it with the rest of the bridge team.

- There was no senior officer on the bridge to assist the master during departure, and the officer of the watch (OOW) was assigned too many duties to enable him to assist the master or monitor the vessel's progress.

- The master's departure plan was not laid down on the large-scale survey field sheets of the area which had been provided to him before departure.

- The vessel's working lights were not turned off for night-time departure nor was a look- out posted where these lights would not hamper visibility.

- The only conventional navigational aid in the area, an "isolated danger" buoy marking the shoal to the south of the berth, is seasonal and had been removed for the winter.

- The master relied solely on parallel indexing for navigation despite the presence of various conspicuous radar targets.

- All engine movements before the grounding were in the ahead mode.

- A video film of the vessel aground and of the adjacent sea-bed indicate that the vessel struck the bottom head-on and remained aground; she did not drift laterally to her grounded position.

- The master's testimony and the entries relative to the grounding made in official documents are inconsistent with the visible damage sustained by the vessel.

- When the bow thruster compartment flooded, the breakers of the vessel's service generators tripped because the bow thruster breaker had a trip delay exceeding that of the generator breakers.

- The emergency generator did not start automatically after the electrical black-out because it was not switched to the automatic start position.

3.1 Causes and contributing factors

The "CSL ATLAS" grounded because the master sailed at night from a port with which he was unfamiliar, did not employ the recognized departure procedure, did not establish either a bridge resource management regime or a voyage plan for leaving the berth, and did not engage either the pilot or tug available.

4.0 Safety Action

4.1 Safety Action Taken

4.1.1 Bridge Resource Management (BRM)

The owners of the "CSL ATLAS", CSL International (CSL), have engaged the Centre for Marine Simulation in St. John's, Newfoundland, to develop a course and train their ships' officers in effective Bridge Resource Management (BRM) techniques. The company has indicated that all CSL masters and chief officers will attend the BRM course during 1995.

4.1.2 Passage Planning

To ensure that masters and navigation officers have the necessary skills to effectively develop passage plans for berth-to-berth navigation, CSL has developed a Passage Planning and Navigation Checklist. The procedural documents are submitted to management for audit on a voyage-by-voyage basis.

Further, to improve proficiency in port manoeuvre planning, CSL has also set up a training program for its masters and navigation personnel.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board's investigation into this occurrence. Consequently, the Board, consisting of Chairperson, John W. Stants, and members Zita Brunet and Hugh MacNeil, authorized the release of this report on .

Appendices

Appendix A - Photographs

Showing bottom damage. (Photo courtesy of Newport News Shipbuilding)

Showing bottom damage. (Photo courtesy of Newport News Shipbuilding)

Appendix B - Sketch of St. George's Bay Showing the Reconstructed Track of the Vessel

Appendix C - Table of Times and Events

| Time | Heading by Course Recorder | Event | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0154 | 068 | Clear F & A | Bell book |

| 0202 | 066.5 | Bow swinging to starboard. | Testimony |

| 0204 | 075 | Dead slow ahead, helm to starboard. | Bell book, testimony |

| 0204.5 | 077.5 | Stop engine. | Bell book |

| 0205 | 080 | Dead slow ahead, helm to starboard. | Bell book, testimony |

| 0206 | 085 | Clearing dock. | Testimony |

| 0207 | 090 | Clearing dock. | Testimony |

| 0208 | 100 | Clearing dock. | Testimony |

| 0209 | 103 | Slow ahead, stern abeam east dolphin. | Bell book, testimony |

| 0210 | 104 | Half ahead to clear shoal. | Bell book, testimony |

| 0211 | 104 | ||

| 0212 | 104 | ||

| 0213 | 104 | ||

| 0214 | 104 | Helm hard to starboard. | Testimony |

| 0215 | 108.5 | Full ahead, vibration aft. | Bell book, testimony |

| 0216 | 109 | Half ahead, v/l squatting. | Bell book, testimony |

| 0217 | 120 | Turning to starboard at 10°/min. | |

| 0218 | 130 | Full ahead to increase turn rate. | Bell book, testimony |

| 0219 | 148 | Stop engine. | Bell book |

| 0219.5 | 155 | Slow & half ahead. | Bell book |

| 0220 - 0221 | 163 - 168 | Full ahead, helm hard to starboard, turn rate down, aground, stop, hard aground. | Bell book, testimony |

Appendix D - Course Recorder Track - Enlarged

Appendix E - Glossary

- A

- aft

- advance (for a given alteration of course)

- Is the distance over which the point of observation on the ship moves in the direction of the original line of advance, measured from the point at which the rudder is put over. A component of the vessel's tactical diameter or turning circle.

- ARPA

- Automatic Radar Plotting Aid

- bell book

- A notebook in which engine movements and related events are recorded.

- BRM

- Bridge Resource Management

- cable

- one tenth of a nautical mile

- CCG

- Canadian Coast Guard

- CCGS

- Canadian Coast Guard Ship

- CGRS

- Coast Guard Radio Station

- CSL

- CSL International

- deck lights

- working lights on deck

- F

- forward

- field sheets

- The data obtained from a hydrographic survey, corrected and accurately plotted on a preliminary sheet before incorporation in a chart.

- IMO

- International Maritime Organization

- Interim Issued by a vessel's Classification Society.

- Commonly referred to as a Certificate Certificate of Seaworthiness. This entitles the ship to make a specified of Class voyage pending permanent repairs being effected.

- kW

- kilowatt(s)

- m

- metre(s)

- N

- north

- navaid

- navigational aid

- NST

- Newfoundland standard time

- OOW

- officer of the watch

- PPI

- Plan Position Indicator

- SI

- International System (of units)

- squat

- The bodily sinkage and change of trim which occurs when a vessel is under way; particularly when passing through shallow water or restricted channels.

- T

- True

- transfer (for a given alteration of course)

- Is the distance over which the point of observation on the ship moves at right angles to the original line of advance, measured from the point at which the rudder is put over. A component of the vessel's tactical diameter or turning circle.

- TSB

- Transportation Safety Board of Canada

- UKC

- Underkeel clearance, the depth of water under the keel.

- U.S.A.

- United States of America

- UTC

- Coordinated Universal Time

- v/l

- vessel

- voyage plan

- A pre-determined plan of the actions to be taken to achieve a safe passage.

- W

- West

- °

- degree(s)

- '

- minute(s)

- "

- second(s)