Bottom contact

Passenger vessel Kawartha Spirit

Halifax, Nova Scotia

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Description of the vessel

The Kawartha Spirit (Figure 1)Footnote 1 is a passenger vessel of steel construction, built in 1964, with a maximum capacity of 200 passengers. It is owned by Murphy Sailing Tours Limited and operated by Ambassatours Gray Line.Footnote 2 The propulsion arrangement consists of 2 diesel engines, twin screw propellers and twin spade rudders. The vessel has a gross tonnage of 85, is 20.18 m in length, and 7.15 m in breadth. The vessel draft at the time of the occurrence was 1.37 m.

The vessel has 2 decks: an enclosed lower deck and an upper deck that has open sides and a retractable roof. The wheelhouse is located on the upper deck and has 1 seat at the wheel. The vessel is equipped with a magnetic compass, a combined display for a radar and chart plotter, an automatic identification system (AIS), 2 very high frequency–digital selective calling (VHF-DSC) radiotelephones, and a depth sounder. However, at the time of the occurrence, only the AIS, chart plotter, and radiotelephones were turned on.

History of the voyage

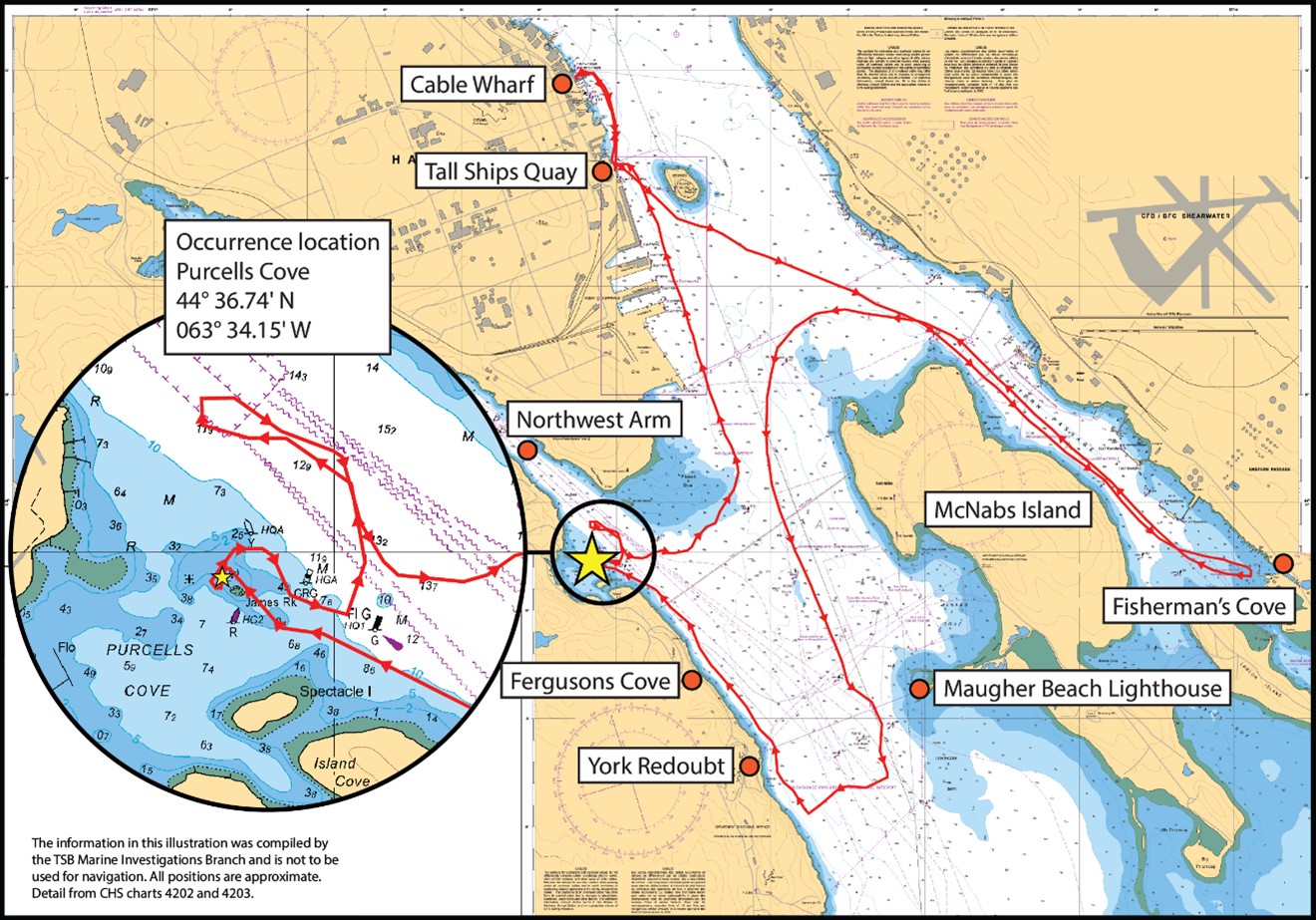

On 26 October 2022, for its first tour of the day, the Kawartha Spirit was scheduled to take passengers from an international cruise ship that was stopped-over in Halifax Harbour. Such tours are a regular business for the Kawartha Spirit; the vessel navigates to Eastern Passage up to Fisherman’s Cove, and then to the western side of McNabs Island. When the vessel reaches the Maugher Beach lighthouse, it may navigate into the Northwest Arm or return to its departure point. Altogether, the tour lasts about 2.5 hours. Figure 2 shows the vessel track on the occurrence voyage.

Before the tour, the master of the Kawartha Spirit and the lead masterFootnote 3 discussed the weather conditions and restricted visibility; the tour then proceeded as scheduled.

At 1100,Footnote 4 the vessel and crew departed from the vessel’s regular docking station at Cable Wharf for a 10-minute transit to Tall Ships Quay, where passengers would board the vessel. Visibility was 2 km with light drizzle, the wind was 5 knots, and the tide was ebbing. At 1130, the Kawartha Spirit departed Tall Ships Quay with 54 passengers, 1 tour guide, and 4 crew members on board. The tour guide gave a passenger safety briefing.

At approximately 1230, while the vessel was transiting the western side of McNabs Island, the mate was alone in the wheelhouse while the master met with passengers throughout the vessel, as was the master’s common practice.

At about 1240, while the vessel was navigating in the vicinity of the Maugher Beach lighthouse, the master returned to the wheelhouse and told the mate to proceed toward York Redoubt. Two minutes later, the mate altered course 80 degrees to starboard as instructed by the master. Moments after the course adjustment, a deckhand brought up a passenger who wanted to be at the wheel. The master welcomed the passenger into the wheelhouse and the passenger took the wheel.Footnote 5 To make room, the mate went just outside the wheelhouse to resume lookout duties. By that time the fog was denser and visibility was approximately 0.4 km; because the view of the shoreline was obscured by the fog, the vessel proceeded closer to shore.

At 1245, when the vessel was approximately 160 m from shore, under the master’s command the course was altered 110 degrees to starboard. The vessel proceeded in the direction of the Northwest Arm, following the shore along York Redoubt and Fergusons Cove, maintaining an average distance of 100 m from shore.

At 1258, just before Purcells Cove, the master sighted a port hand (green) buoy on the starboard side of the Kawartha Spirit. The master looked at the chart plotter to assess the vessel’s position, but could not locate the green buoy on the display. At 1259, the master altered the vessel’s course to starboard in an attempt to position the vessel so that the green buoy was on the port side. However, less than 30 seconds later, the Kawartha Spirit touched bottom at a speed of 7 knots in position 44°36.44′ N 063°34.07′ W (Figure 2) and lost propulsion. At this time, the tide height was 0.8 m.

The passenger who was in the wheelhouse left to rejoin the other passengers and the mate returned inside. At 1301, the master restarted the engines and set the propulsion astern. The 2 deckhands and the tour guide went to the wheelhouse for information about the situation. After providing a briefing, the master ordered the deckhands to verify each compartment for watertight integrity, and the tour guide returned to the passengers to give them an update.

At 1303, the master set the vessel’s course, via magnetic compass, to return to Tall Ships Quay to disembark the passengers. The deckhands regularly monitored vessel compartments for water ingress throughout the return voyage. At 1317, the master informed the lead master via cellphone about the occurrence.

At 1350, the Kawartha Spirit arrived at Tall Ships Quay, and the passengers and tour guide disembarked.

At 1404, with the master and crew on board, the vessel departed for Cable Wharf; 10 minutes later the vessel docked at its destination.

At 1500, the lead master reported the occurrence to Halifax Marine Communication and Traffic Services approximately 2 hours after the occurrence.Footnote 6 A Transport Canada Marine Safety Duty Officer subsequently placed a restriction on the vessel pending repairs, inspection, and clearance to sail.

At approximately 1510, an underwater inspection took place, during which it was confirmed that both propellers were bent, the port shaft had been moved toward the stern, and the port rudder was missing. There were also some scratches along the keel and indents on the port side bottom hull plating.

Voyage planning

Voyage planning provides vessel operators with an opportunity to assess the route and speeds for a vessel’s passage based on the prevailing conditions. It includes consideration of weather, tides, vessel limitations, navigational hazards, and a contingency plan should the need arise. Under the Navigation Safety Regulations, 2020, vessel operators are required to ensure their intended voyage has been planned.Footnote 7

Voyage planning involves 4 distinct stages: gathering all information relevant to the contemplated passage, making a detailed plan of the whole passage from the point of departure to the point of arrival, executing the plan, and monitoring the vessel's progress as the plan is executed.

During their initial training, masters of vessels operated by Ambassatours Gray Line are informed of the general areas of vessel operation and vessel operating limits, as determined by Transport Canada and recorded on each vessel’s inspection certificate.

On the day of the occurrence, the master of the Kawartha Spirit navigated an unplanned passage within the general area of operation, which is limited to Halifax Harbour north of Maugher Beach lighthouse, by coming closer to shore than was normal.

Navigating in restricted visibility and safety management systems

Navigating in restricted visibility requires vessel operators to adapt regular navigation practices to ensure the safe passage of their vessel. For example, the Collision Regulations require operators to have a lookout and adopt a safe speed.Footnote 8 The International Maritime Organization recommends that bridge team members avoid disruptions and distractions in fulfilling their duties when increased vigilance is needed.Footnote 9

To navigate safely, operators must use and manage effectively all resources available to them and continuously monitor their vessel’s position. It is important to configure navigational equipment to optimize the information available to assist with safe navigation and predict a vessel’s track. Cross-checking the position with a second piece of navigational equipment can also help operators maintain awareness of their vessel’s position and identify navigational errors.

A safety management system (SMS) can help ensure that members at all levels of an organization have the knowledge and the tools to manage risk effectively, as well as the necessary information to make sound decisions in all operating conditions, routine and emergency.

Ambassatours Gray Line has a voluntary SMS in place covering some emergency procedures and some standard operating procedures. At the time of the occurrence, the SMS (revised in 2017) did not include requirements for voyage planning, deviation of routes, procedures for the bridge team to follow in restricted visibility, or procedures for visitors to the wheelhouse.

Transport Canada has proposed new regulations intended to expand formal SMS requirements to the majority of Canadian and foreign vessels operating in Canadian waters.Footnote 10 The proposed Marine Safety Management System Regulations will apply to vessels such as the Kawartha Spirit.

Previous occurrences

The TSB has previously investigated other occurrences where issues related to voyage planning, navigating in restricted visibility, and SMS have been identified.Footnote 11 The following occurrences are particularly relevant:

M22P0029 (water taxi C12997BC [Rocky Pass]) – On 25 January 2022, the water taxi known as Rocky Pass ran aground with 5 people on board in Coomes Bank, British Columbia. Emergency services evacuated those on board, including 4 injured passengers, and towed the vessel to Tofino, British Columbia. The investigation highlighted the importance of having a formal voyage plan to help identify navigational hazards and adaptations required by operators in restricted visibility.

The TSB has also previously investigated other occurrences in which the operator’s notification of the occurrence to the Canadian Coast Guard was delayed:

M17C0179 (Island Queen III) – On 08 August 2017, at approximately 1246 Eastern Daylight Time, the passenger vessel Island Queen III, with 279 passengers, 10 crew members, and an entertainer on board, was on a 3-hour cruise in the Thousand Islands area of the St. Lawrence River when it made bottom contact off Kingston, Ontario. The investigation highlighted the importance of alerting search and rescue resources in a timely manner following an occurrence to ensure a timely, effective, and coordinated response.

TSB Watchlist

The Watchlist identifies the key safety issues that need to be addressed to make Canada’s transportation system even safer. Safety management is a Watchlist 2022 issue. As this occurrence demonstrates, even when a company has safety management processes in place, it is not always able to demonstrate that hazards are being identified or that effective risk-mitigation measures are being implemented.

Safety action taken

Following the occurrence, Ambassatours Gray Line created a standard operating procedure for its vessels operating in restricted visibility and added the procedure to its SMS. The company has also modified its training for new operators with a focus on the SMS procedures relating to on-board operations.

Safety messages

It is important that vessel operators, regardless of the size of their vessel, make a careful assessment of their intended route and any deviations by considering potential dangers to navigation, as well as the prevailing weather, visibility, and other relevant factors.

Reliance on a single electronic aid to navigation, especially in restricted visibility, can result in accidents. To navigate safely, cross-checking vessel position using all available means, including visual aids, depth sounder, radar, and chart plotter, can help operators maintain awareness of their vessel’s position and identify navigational errors.

Establishing SMS procedures for navigation in restricted visibility (including watch composition, lookout and navigation practices, and access to the bridge) will help the crew follow regulations and best practices.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s investigation into this occurrence. The Board authorized the release of this report on . It was officially released on .