Uncontrolled movement and derailment

Canadian Pacific Railway Company

Cut of cars

Mile 196.7, Belleville Subdivision

Toronto Yard

Toronto, Ontario

The Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB) investigated this occurrence for the purpose of advancing transportation safety. It is not the function of the Board to assign fault or determine civil or criminal liability. This report is not created for use in the context of legal, disciplinary or other proceedings. See Ownership and use of content. Masculine pronouns and position titles may be used to signify all genders to comply with the Canadian Transportation Accident Investigation and Safety Board Act (S.C. 1989, c. 3).

Summary

On 13 March 2022, at about 1300 Eastern Daylight Time, during switching operations at Canadian Pacific Railway Company’s Toronto Yard in Toronto, Ontario, a cut of 103 cars ran uncontrolled for about 3200 feet down the descending grade of track G05, resulting in the derailment of the leading 7 cars, 1 of which came to rest foul of the main track. Three of the derailed cars were loaded with sulphuric acid (UN1830), and 2 were residue tank cars that had last contained sulphuric acid; there were no leaks of dangerous goods. No one was injured.

1.0 Factual information

On 12 March 2022, at about 0900,Footnote 1 Canadian Pacific Railway Company (CP) Footnote 2 freight train 119-12 departed Smiths Falls,Footnote 3 destined for CP’s Toronto Yard in Toronto, travelling westward on the Belleville Subdivision. The train consisted of 2 locomotives—1 at the head end and 1 at position 43—and was hauling 166 freight cars (100 loaded cars with mixed freight and 66 empty cars); it measured about 10 000 feet and weighed about 10 000 tons, including the locomotives.

1.1 Toronto Yard

Toronto Yard is located in the Agincourt neighbourhood of Scarborough, in the Greater Toronto Area. Movements within the yard are conducted under Canadian Rail Operating Rules (CROR) Rule 105, Operation on non-main track.Footnote 4

Operating employees work at Toronto Yard around the clock, 7 days per week, on various shifts. Crews within the yard are responsible for operating a combination of yard assignments, local switching assignments, and main-track freight trains. There are also several CP Mechanical employees who perform supporting roles.

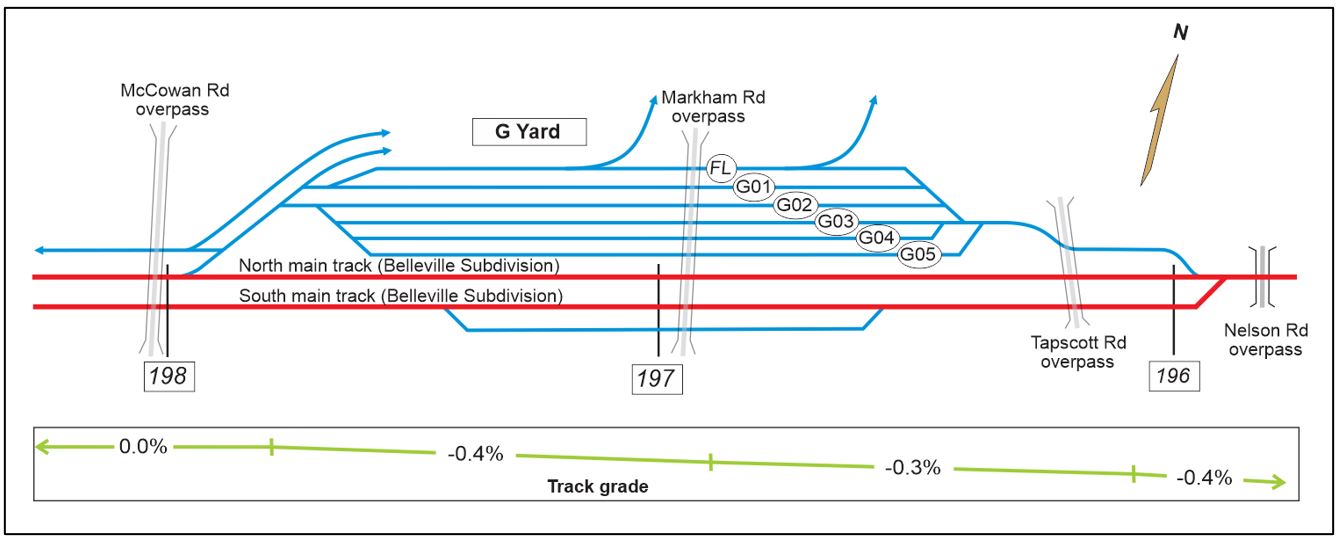

Upon entry into Toronto Yard from the north main track at Mile 196.7 of the Belleville Subdivision, rail traffic is pulled westward and placed into one of 5 tracks in G Yard (Figure 1). Rail traffic is then redistributed into other destination tracks where trains are built in preparation for further handling and departure.

1.2 The occurrence

The train arrived at Toronto Yard at about 1800. The crew was instructed to yard the entire train on track G05. This would leave about 4000 feet of the train’s tail end on the north main track, foul of 2 signal-controlled locations.Footnote 5 The crew expressed concern to the yardmaster about this approach and, after further discussion, it was decided that the crew would separate the train into 2 portions, leaving the tail end on track G05 and doubling overFootnote 6 the head end to track G03.

The train exited the north main track of the Belleville Subdivision and pulled westward into track G05 at Toronto Yard. Aware that a cut of cars would be secured with hand brakes, the locomotive engineer (LE) brought the train to a stop by making a minimum air brake application; he then applied the locomotive independent brake and made a further 2 psi brake pipe pressure reduction. Meanwhile, the conductor detrained from the locomotive at the west switch of track G05 to be in position to separate the 2 portions of the train and secure the cut of cars that would remain on track G05.Footnote 7

The train stopped with the locomotives and the first 63 cars west of the west switch, on level ground, while the remaining 103 cars were on a 0.45% descending grade. In order to separate the train between the 63rd and 64th cars, the LE released the air brakes throughout the train while the conductor applied the hand brake to the first 5 consecutive cars of the cut that was to remain on track G05 (cars in positions 64 to 68).Footnote 8

After applying the hand brake on the 68th car, the conductor was concerned that 5 hand brakes might not have been sufficient. He noticed that the hand brake on the 69th car was easily accessible and applied it as well. Once all 6 hand brakes were applied, he informed the LE that they could begin the hand brake effectiveness test.Footnote 9

To perform the test, the LE released the locomotive independent brake, moved the throttle to position 1, and began reversing to push against the cars; when he judged that he had pushed the cars far enough, he reapplied the independent brake. Meanwhile, the conductor, from his position near the cars with hand brakes applied, observed a small displacement on the car in position 64 (the first car with an applied hand brake) and saw that the cars behind it were not moving; he accordingly judged that the test was successful.

In preparation for uncoupling the cars, the conductor closed the brake pipe angle cock between the cars in positions 63 and 64 and informed the LE that he had done so. The LE then triggered the emergency braking feature on the end-of-train device, which applied the air brakes to the cars in positions 64 to 166.Footnote 10 The conductor, noticing that the 2 coupled knuckles between cars 63 and 64 were still in tension, asked the LE to push back to remove the tension, as he was not able to use the operating lever to open the knuckles to uncouple the cars. The LE made another reverse move, and the conductor then uncoupled the cars.

The crew left the secured cut of cars on track G05. It consisted of 103 cars (51 loaded and 52 empty), measured 6579 feet, and weighed 7979 tons. They then completed the double-over operation and secured the head end of the train, consisting of the locomotives and remaining 63 cars, on track G03. Confident that the 2 cuts of cars were fully secured, the crew members completed their shift and left for the day.

The next morning, at about 1145, in preparation for switching the 103 cars from track G05,Footnote 11 CP Mechanical employees began bleeding the air brake system, including releasing the emergency air brakes on each of the cars, starting from the east and working westward. After the air brakes were exhausted from the last of the 103 cars, the cut of cars began to roll uncontrolled eastward down the grade, with the 6 hand brakes still fully applied.

Employees working within proximity of track G05 broadcast over the designated standby channel that the uncontrolled movement was occurring. Operations management employees from a nearby office building, as well as nearby CP Mechanical employees, responded and attempted to board the rolling cars to apply additional hand brakes. However, this effort was abandoned as the movement accelerated too quickly and entraining the cars became unsafe.

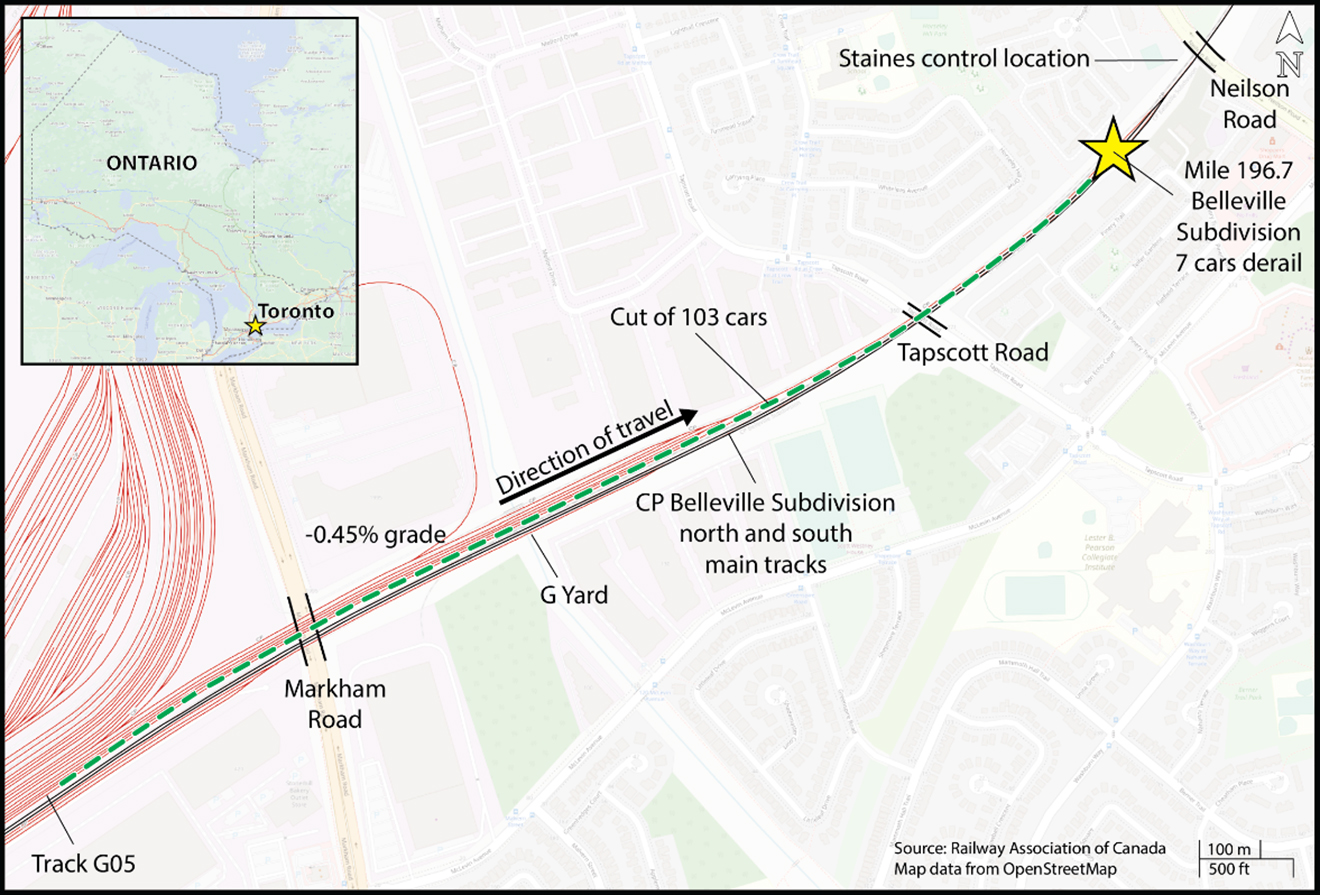

The cut of cars ran uncontrolled for approximately 3200 feet. The cars then encountered a split switch derailFootnote 12 at Mile 196.7 of the Belleville Subdivision and the leading 7 cars derailed (Figure 2).

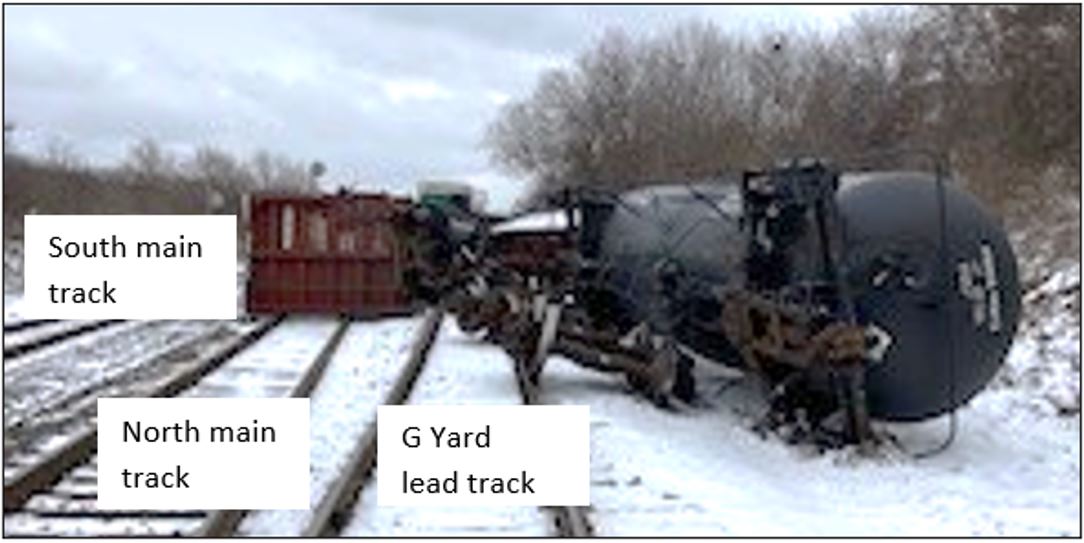

The first car to derail, a tank car loaded with sulphuric acid (UN1830), came to rest on its side. The next car, a box car loaded with drywall, also came to rest on its side, foul of the north main track (Figure 3). The remaining 5 cars—2 tank cars loaded with sulphuric acid, 2 residue cars last carrying sulphuric acid, and 1 car loaded with wood pulp—derailed upright. There were no leaks of dangerous goods, and no one was injured.

At the time of the occurrence, the temperature was −3 °C, and the wind was north-northeast at 20 km/h. The skies were mostly cloudy, but visibility was good.

1.3 Crew information

The train crew consisted of an LE and a conductor. They were both qualified for their positions, met fitness and rest requirements, and were familiar with Toronto Yard, the grade in G Yard, and hand brake requirements for securing equipment. They both had over 30 years of service.

1.4 Subdivision information

The CP Belleville Subdivision extends from Smiths Falls (Mile 0.0) to Leaside (Mile 206.3). Train movements on the Belleville Subdivision are controlled by the centralized traffic control system, as authorized by the CROR, and supervised by a rail traffic controller located in Calgary, Alberta.

1.5 Hand brake requirements

All railway rolling stock is equipped with a hand brake—a mechanical brake independent of the air brake system. Hand brakes are manually applied by either turning a hand brake wheel or by operating a ratchet lever. This causes the brake shoes to press against the wheel tread surface and prevent the wheels from rotating or retard their motion.

The number of hand brakes required to provide the brake retarding force needed to prevent stationary rolling stock from moving depends on several factors, such as the rolling stock tonnage and track grade. Heavier rolling stock and rolling stock on descending grades require a greater retarding force, and hence a higher number of applied hand brakes, to remain stationary. For this reason, the CROR require a minimum number of hand brakes to be applied in certain situations, and the rules are often complemented by company instructions.

1.5.1 Canadian Pacific’s hand brake requirements for non–main-track territory

At CP, as prescribed by and in compliance with the CROR, hand brake requirements are contained in CP’s General Operating Instructions (GOI).

With respect to requirements for non–main-track territory such as yards, the GOI state, in part:

6.1 When cars are left unattended on other than a main track, siding, or at a high risk location, a sufficient number of hand brakes must be applied and tested for effectiveness:

a) one car must be left with one hand brake applied; and

b) two or more cars must be left with a sufficient number of hand brakes applied, at least one, unless a greater number is prescribed.Footnote 13

There is no record that, at the time of the occurrence, there were supplemental instructions prescribing a specific minimum number of applied hand brakes for the tracks in G Yard.

1.5.2 Securement process history for G Yard

Over the years, there were numerous changes to car securement practices in G Yard. Between 2008 and 2012, the practice was to apply a minimum of 5 hand brakes at both the east end and west end of the tracks. A change was made in about 2012 to apply a minimum of 5 hand brakes at only the east end (the bottom of the grade). This was again changed in about 2014 such that, at the time of the occurrence, hand brakes could be applied at either end of the train based on instructions from the west tower. In each case, the change was not made based on considerations for variations in tonnage of rolling stock.

In 2020 and 2021, 2 bulletins were issued regarding car securement processes when switching without air at G Yard:

- On 17 August 2020, CP issued Information Bulletin SI-063-20, which required a second employee to ride on the east end of a movement without air brake securement throughout the rail cars when shoving in an eastward direction into G Yard.Footnote 14 In addition, the bulletin required crews to be in a position to observe the movement when pulling cars in G Yard in a westward direction.Footnote 15

- On 01 March 2021, CP issued Operating Bulletin SO-014-21, which further defined the actions to be taken by the aforementioned second employee. It stated, in part: “For eastward shoving movements without air, the second employee must remain with the railcars until the equipment is properly secured and tested for effectiveness.”Footnote 16 The bulletin also clarified that, for westward movements, the second employee must ride the tail end of the movement (not just observe) or be in position to take effective action, if required.

Beyond the requirements in the GOI and the instructions in these bulletins, at the time of the occurrence, there were no other instructions or requirements for train crews securing cars in G Yard.

1.6 Hand brake effectiveness tests

The effectiveness of a hand brake is directly proportional to the amount of force exerted by the person when applying the hand brake, which can vary widely from one person to another. Hand brake effectiveness can also be reduced due to factors such as service wear and a lower coefficient of friction of the brake shoes from conditions such as the presence of ice or snow. When some of the hand brakes on rolling stock are not fully effective, more hand brakes are needed to achieve the brake retarding force necessary to hold it stationary.

In practice, operators do not know how much retarding force they are applying through the hand brake wheel, as hand brakes are not equipped with the means to provide this information. Nor do operators know the coefficient of friction of the brake shoes or whether a hand brake’s effectiveness is reduced due to service wear. The only available means to determine whether a sufficient number of hand brakes has been applied, therefore, is to perform a hand brake effectiveness test.

Requirements for the hand brake effectiveness test are provided in CROR Rule 112(vi), which states:

(vi) Testing Hand Brake Effectiveness

When testing the effectiveness of hand brakes, ensure all air brakes are released and:

(a) allow the slack to adjust. It must be apparent when slack runs in or out, that the hand brakes are sufficient to prevent the equipment from moving; or

(b) apply sufficient tractive effort to determine that the hand brakes prevent the equipment from moving when tractive effort is terminated.

If the effectiveness of hand brakes is not sufficient to prevent the equipment from moving, apply one or more additional hand brakes and re-test.Footnote 17

CP’s GOI stipulate the same requirements as in the CROR.Footnote 18

1.6.1 Complexities in establishing that a hand brake effectiveness test is successful

Completing a hand brake effectiveness test correctly requires a good understanding of slack action and the factors that affect it during rolling stock securement operations.

Slack action is the amount of movement required before one car transmits its motion to an adjoining coupled car. The amount of slack between cars depends on the type of draft gear on each of the cars. For each draft gear, there can be up to 3 inches of slack when fully compressed, and an additional ½ inch of slack at the knuckle and coupler interface.Footnote 19

Slack action travels along the length of a train in a domino effect: the first car moves, then transmits its motion to the adjoining car, which then moves, and so on. A significant amount of force can be required to fully compress or stretch the slack. Depending on the applied force, rolling resistance, and grade, the cars might not fully compress or stretch the full amount before they start to move.

Topographic track configurations vary significantly in terms of curvature and gradient, both from yard to yard and within the same yard. In addition, the length, weight, and car configurations of the rolling stock to secure vary with each assignment. When performing a hand brake effectiveness test, there is no specific rule on the locomotive tractive effort to be applied to the rolling stock being secured, or on how much time must be allowed to elapse for slack action to travel. The cars must be pushed or pulled the amount necessary so that the combined slack action reaches the cars that have their hand brake applied, and someone on the ground next to those cars can verify that they are not moving. When securing equipment, train crews must rely on their knowledge, experience, and judgment.

1.6.2 Hand brake effectiveness test for the cut of cars on track G05

To gain insight into the steps performed and the slack action that developed during the hand brake effectiveness test in this occurrence, the TSB reviewed data from the locomotive event recorder (LER) and calculated the approximate distance that the train moved during the test (Appendix A).

The LER data review indicated that the lead locomotive pushed 21.7 feet during the reverse movement of the hand brake effectiveness test. Therefore, given that there was slack to be compressed on the head-end 63 cars, the reverse movement compressed some of this slack until the conductor saw what he believed to be the free slack reaching the first car with an applied hand brake. He judged that sufficient reverse movement had been made to test the hand brake effectiveness. After having pushed back 16.5 feet, the LE started to reapply the independent brake on the locomotives before finishing the hand brake effectiveness test.

The LER data also indicated that, when the LE later pushed back on the cars to release the tension in the knuckles to separate the 2 cuts of cars, he pushed a further 9 feet.

1.7 Other recent uncontrolled movements in Toronto Yard

Including this occurrence, 4 significant uncontrolled movements have taken place in Toronto Yard over the past 5 years, including several in G Yard. This prompted the TSB to issue Rail Transportation Safety Advisory Letter 03/23 to Transport Canada (TC) in March 2023.

R18H0039 – On 14 April 2018, a CP yard crew was performing switching operations at Toronto Yard without air brakes, when the locomotive consist and 88 cars rolled uncontrolled on a 0.88% descending grade. The movement continued rolling uncontrolled for about 3 miles and ran through the switch at Signal 1952B that was protecting the main track and displaying a stop indication. There was no derailment or collision and there were no injuries. Footnote 20

R22H0020 – On 20 February 2022, a cut of 85 cars rolled uncontrolled down the descending grade of track G01 in Toronto Yard. The cars travelled about 3200 feet until the 4 leading cars derailed at the split switch derail at Mile 195.9 of the Belleville Subdivision. At the time of the occurrence, there were winds of 70 km/h. Before the occurrence, the cut of cars had been stationary on the track for about 28 hours. The cars had been secured with hand brakes, in accordance with CP policy, and had been left with emergency air brakes applied. The cars rolled uncontrolled, with the hand brakes still applied, after CP personnel released the air brakes on all the cars in preparation for switching operations without air. No one was injured.

R23T0014 – On 15 January 2023 (less than 1 year after this occurrence), 67 cars ran uncontrolled for about 3400 feet on the descending grade of track G05 in Toronto Yard during switching operations, resulting in the derailment of 4 residue tank cars that had last contained dangerous goods. The 4 cars derailed after they had travelled over a recently installed split switch derail located at the end of track G05. Footnote 21 The cars ran uncontrolled, even though 13 hand brakes had been applied. There was no release of product and there were no injuries.

1.8 TSB occurrence statistics for uncontrolled movements

From January 2013 to December 2023, there were 617 occurrences reported to the TSB related to unplanned and uncontrolled movements among all federally regulated railways in Canada (Table 1).

| Type of uncontrolled movements | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss of control | 3 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 20 |

| Switching | 24 | 21 | 22 | 18 | 21 | 27 | 35 | 12 | 16 | 22 | 14 | 232 |

| Securement | 42 | 38 | 37 | 29 | 39 | 34 | 40 | 30 | 32 | 27 | 17 | 365 |

| Total | 69 | 59 | 60 | 51 | 62 | 66 | 77 | 43 | 49 | 49 | 32 | 617 |

Note: The data summarizing the number of unplanned and uncontrolled movements each year have not been adjusted for variations in annual rail traffic volumes.

The TSB has categorized unplanned and uncontrolled movements into 3 types:

- Loss of control: when an LE or a remote control locomotive system operator cannot control a locomotive, a car, a cut of cars, or a train with available locomotive and/or train air brake systems.

- Switching: when a movement is performing switching, and 1 or more cars

- being switched run farther than planned, resulting in a collision or in the limits being exceeded;

- that are attended roll uncontrolled; or

- roll back.

The vast majority of these incidents occur in yards.

- Securement: when a car, a cut of cars, or a train is left unattended and begins to roll away uncontrolled, usually because

- an insufficient number of hand brakes have been applied to a car, a cut of cars, or a train; and/or

- a car (or cars) has faulty or ineffective hand brakes.

Since 2012, in addition to this occurrence, the TSB has investigated 17 occurrences that involved unplanned and uncontrolled movements throughout the industry (Appendix B); 6 of these were also related to securement.

1.9 Previous recommendation and safety concern regarding uncontrolled movements

There is 1 active Board recommendation related to uncontrolled movements resulting from insufficient equipment securement; the Board has also issued 1 safety concern related to uncontrolled movements in general.

On 06 July 2013, a train carrying petroleum crude oil (UN1267), left unattended on a descending grade with insufficient securement, rolled uncontrolled and derailed in the centre of the town of Lac-Mégantic, Quebec, directly causing the death of 47 people and destroying the town’s core and main business area. Footnote 22 As a result of the TSB investigation, the Board recommended that

the Department of Transport require Canadian railways to put in place additional physical defences to prevent runaway equipment.

TSB Recommendation R14-04

In its December 2023 response to this recommendation, TC indicated that addressing the multi-faceted issue of uncontrolled movement of railway equipment remained a priority for the Department, including ensuring that current physical defences are effective. To this end, the Department has not only strengthened its regulatory framework, but has also made substantial strides in researching technology aimed at mitigating the risk associated with uncontrolled movements. TC has also initiated a research study that will assess human factors related to uncontrolled movements in the rail industry.

These actions are complemented by the numerous operating rule changes that have been made to strengthen operating procedures to reduce uncontrolled movements. This includes new rule provisions for the securement of trains stopped on mountain grade, use of hand brakes, and requirements for locomotives that are equipped with roll-away protection.

In its March 2024 assessment of TC’s response, the Board indicated that it was encouraged by the safety action taken to date. The number of occurrences in 2023 is the lowest reported over the last 10 years and is below the 10-year average of 58 reported between 2013 and 2022. While the number of uncontrolled movements has decreased since 2020, the number of occurrences reported in 2020 and 2021 may be due in part to the impact of COVID-19 on the rail industry as well as other disruptions to service. Despite this recent decrease in occurrences, additional data are required to determine whether this is a statistically significant trend and whether the defences that are in place are, in fact, achieving the desired outcome. Notwithstanding this recent decrease in reported occurrences and improvements to administrative defences, the Board believes that additional layers of physical defences are the most effective means to reduce the risk of uncontrolled movements. Therefore, the Board considered TC’s response to Recommendation R14-04 to be Satisfactory in Part. Footnote 23

In March 2016, an uncontrolled movement of equipment travelled from Sutherland Yard in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, onto the main track; there were no injuries and there was no derailment. The TSB investigation into this occurrence determined that, despite TC and industry initiatives, the desired outcome of significantly reducing the number of uncontrolled movements had not yet been achieved. Consequently, the Board issued the following safety concern:

The Board is concerned that the current defences are not sufficient to reduce the number of uncontrolled movements and improve safety.Footnote 24

1.10 Safety management systems

A safety management system (SMS) is an internationally recognized framework that allows companies to identify hazards, manage risks, and make operations safer. An SMS improves safety by building on existing processes, demonstrating corporate due diligence, and growing the overall safety culture.

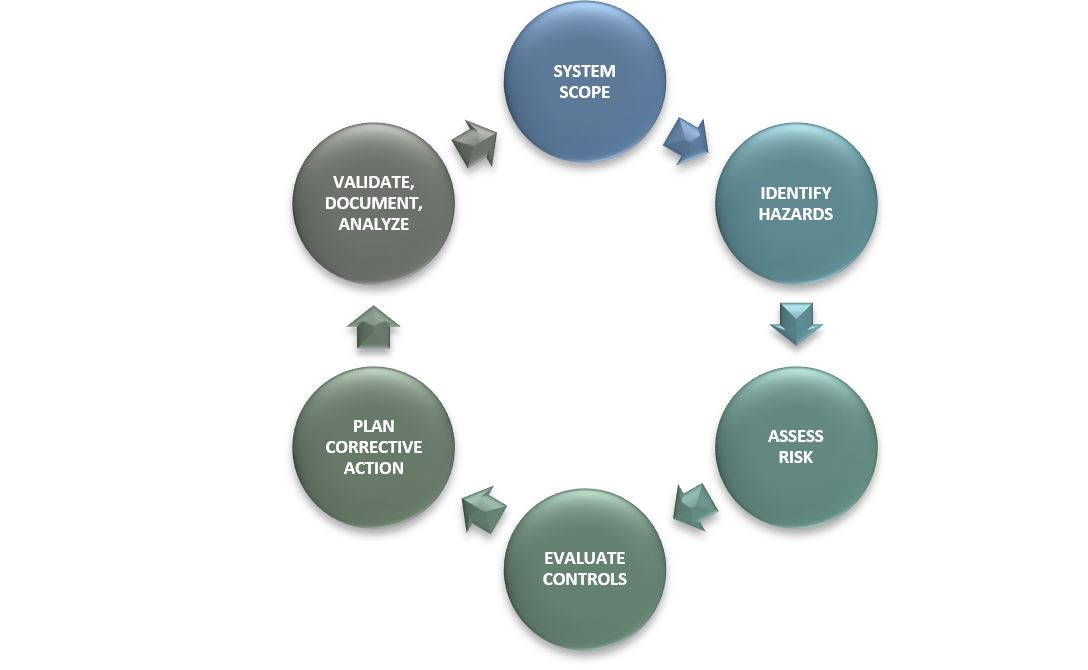

Safety management is a systemic approach to safety—engaging, but not limited to, a continuous safety improvement process (Figure 4). An effective SMS incorporates the 4 pillars of safety management: safety policy and objectives, safety risk management, safety assurance, and safety promotion.

The SMS framework is not new to Canadian railway operations; SMS regulations were introduced in 2001. In 2013, the investigation into the fatal derailment in Lac-MéganticFootnote 25 identified shortcomings in these regulations that led to their revision in 2015. Under the Railway Safety Management System Regulations, 2015 (SMS Regulations), railway companies must develop an SMS that includes processes for identifying safety concerns,Footnote 26 for conducting risk assessments, and for implementing and evaluating remedial (safety) action.Footnote 27,Footnote 28 However, a rules-compliant process does not necessarily ensure an effective SMS.

Safety action taken is one step in the SMS process. Therefore, it is expected that any safety action taken as a result of an occurrence is part of a continuous safety improvement process, where the scope of change is defined, the hazards are identified, the risks are assessed, the safety actions are implemented and evaluated, and the entire process is documented. Consequently, the effectiveness of the safety action taken (its effectiveness in reducing the likelihood or severity of an undesired event) can be objectively measured.

The TSB investigates occurrences to identify safety deficiencies, including those in a company’s SMS, and reports on instances in which the safety system could manage risk more effectively or proactively.

1.10.1 Canadian Pacific’s safety management system

CP, in accordance with the SMS Regulations, has developed and implemented an SMS, which includes a risk assessment policy and procedure. The risk assessment procedure outlines the conditions under which a risk assessment must be conducted. It states, in part:

A confidential risk assessment must be conducted […] whenever:

- A “Safety Concern” (i.e. a hazard or condition that may present a direct safety risk to employees, or pose a threat to safe railway operations) is identified through analysis of safety data;

- A proposed change to CP Operations that could:

- introduce a new hazard to the workplace resulting in adverse effects;

- negatively impact or contravene any existing policy, procedure, rule or work practice used to meet regulatory compliance or any CP requirements or standards;

- create or increase a direct safety risk to employees, railway property, property transported by the railway, the public or property adjacent to the railway; or

- require authority by a regulatory agency to implement.

A risk assessment must be performed as soon as practicable after the identification of a safety concern; prior to the commencement of the work affected or implementation of the proposed changes. […]Footnote 29

The car securement practices in G Yard changed several times over the years. There have also been 4 significant uncontrolled movements in Toronto Yard over the past 5 years. However, CP has no record that, before this occurrence, it conducted a risk assessment in response to these uncontrolled movements or to support the changes to its securement instructions.

1.10.2 Previous recommendation related to Canadian Pacific’s safety management system

Following its investigation of an occurrence on 04 February 2019, in which a CP freight train derailed on a steep descending grade near Field, British Columbia, and the 3 crew members on board were fatally injured,Footnote 30 the TSB determined that some railway companies’ SMSs were not yet effectively identifying hazards and mitigating risks in rail transportation. When hazards are not identified—either through reporting, data trend analysis, or by evaluating the impact of operational changes—and when the risks that they present are not rigorously assessed, gaps in the safety defences can remain unmitigated, increasing the risk of accidents.

The Board also determined that, until CP’s overall corporate safety culture and SMS framework incorporate a means to comprehensively identify hazards, including the review of safety reports and data trend analysis, and assess risks before making operational changes, the effectiveness of CP’s SMS will not be fully realized. Therefore, the Board recommended that

the Department of Transport require Canadian Pacific Railway Company to demonstrate that its safety management system can effectively identify hazards arising from operations using all available information, including employee hazard reports and data trends; assess the associated risks; and implement mitigation measures and validate that they are effective.

TSB Recommendation R22-03

In its December 2023 response to this recommendation, TC indicated that it completed numerous activities over the past 16 months toward assessing the effectiveness of CP’s SMS. In July 2022, TC required periodic SMS filings from CP in order to help assess the efficacy of CP’s processes for hazard identification, identifying safety concerns, and risk assessment. TC also conducted 2 targeted audits of CP’s SMS and, as a result of these audits, it informed CP of its expectations, including the amendment of its process for identifying safety concerns. CP’s amended process was received, and TC is reviewing and assessing it. In addition, TC increased its inspection frequency of CP’s occupational health and safety committees by 7 inspections between fiscal years 2020-2021 and 2021-2022.

In its February 2024 assessment of TC’s response, the Board indicated that it was encouraged that TC conducted targeted audits of CP’s SMS and increased its inspection frequency for occupational health and safety committee monitoring, and that it looked forward to receiving the results of TC’s review and assessment of CP’s amended SMS processes. The Board assessed TC’s response to Recommendation R22-03 to show Satisfactory Intent.Footnote 31

1.11 TSB Watchlist

The TSB Watchlist identifies the key safety issues that need to be addressed to make Canada’s transportation system even safer. This occurrence involves 2 of these issues.

1.11.1 Unplanned/uncontrolled movement of railway equipment

Unplanned/uncontrolled movement of railway equipment is a Watchlist 2022 issue and has been a Watchlist issue since 2020.

Uncontrolled movements are low-probability events but, when they occur, either on or off the main track, they can have catastrophic consequences—particularly if they involve dangerous goods.

Despite significant safety action taken by TC and the railway industry to reduce the number of unplanned and uncontrolled movements of rail equipment, uncontrolled movements continue to occur, posing a significant risk to the rail transportation system.

ACTION REQUIRED: Unplanned/uncontrolled movement of rail equipment Although all 3 types of uncontrolled movements share some common causes, they each require unique strategies either to prevent the occurrences from happening or to reduce the associated risks. TC, the railway companies, and labour unions must collaborate; devise strategies; and implement not just administrative defences, but also physical defences to address each type of uncontrolled movement. For the safety of railway workers, the environment, and the public, the TSB wants to see a downward trend in the number of uncontrolled movements. |

1.11.2 Safety management

Safety management is a Watchlist 2022 issue and has been a Watchlist issue since 2010.

Federally regulated railways have been required to have an SMS since 2001, and regulatory requirements were significantly enhanced in 2015. However, the expected changes in safety culture and safety improvements with the implementation of SMS have not yet been demonstrated by industry. TSB investigations continue to identify hazards that are not always recognized and subsequently risk-assessed by operators so that effective risk mitigations can be taken. As a result, the TSB has determined that railway companies’ SMSs are not yet effectively identifying hazards and mitigating risks in rail transportation.

ACTION REQUIRED: Safety management The issue of safety management in rail transportation will remain on the Watchlist until operators demonstrate to TC that their SMS is effective. |

2.0 Analysis

The analysis will focus on the hand brake effectiveness test performed by the crew to validate that a sufficient number of hand brakes was used to secure the cut of cars on track G05, securement practices of rolling stock in G Yard of Toronto Yard, and the management of the risks associated with the operational changes implemented over the years with respect to the securement of cars in G Yard.

2.1 The occurrence

On 12 March 2022, a Canadian Pacific Railway Company (CP) crew secured 103 cars on track G05 in CP’s Toronto Yard with 6 hand brakes and performed the hand brake effectiveness test. The cars were left with hand brakes and emergency air brakes applied.

About 18 hours later, in preparation for switching the 103 cars from track G05, CP Mechanical personnel released the air brakes on the cut of cars. Once the air brakes were released from all the cars, the 6 applied hand brakes were insufficient to hold the cars, and they began to roll uncontrolled down the 0.45% grade.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

The derailment occurred when a cut of 103 stationary cars, which had been secured for about 18 hours with 6 hand brakes and the emergency air brakes, ran uncontrolled down a 0.45% grade after the air brakes were released.

2.2 Hand brake effectiveness test

In this occurrence, the crew applied a greater number of hand brakes than CP’s practice required and were confident, based on the results of the hand brake effectiveness test, that they had fully secured the cut of cars on track G05.

Both crew members were experienced employees, each having in excess of 30 years of service. They had safely and securely applied hand brakes countless times throughout their careers, including within G Yard; they fully understood the process.

To gain insight into how the hand brake effectiveness test was performed and what led the crew to believe that it was successful, TSB investigators reviewed train-handling data from the locomotive event recorder (LER). The data indicated that the lead locomotive had pushed a distance of 21.7 feet during the reverse movement of the hand brake effectiveness test. Not consistent with Canadian Rail Operating Rules (CROR) Rule 112(vi), after having pushed back 16.5 feet, the locomotive engineer (LE) started to reapply the independent brake on the locomotives before finishing the hand brake effectiveness test, which reduced the force being applied to the rail cars during the test.

The locomotive buff force imparted during the hand brake effectiveness test travels along the length of a train through the first car by compressing the slack in the draft gear that connects the car and transmitting its motion to the adjoining car. This force then continues to propagate to the next car, and so on, until the force reaches the first car with the hand brake applied.

In this occurrence, force was applied by the locomotive until the LE judged that he had pushed the cars far enough, at which point the conductor judged that the test was successful. The fact that the conductor was not successful in opening the operating lever of car 63 to open the knuckle and separate the cut indicates that the knuckles were still in tension and that the force applied by the locomotive to the cars and the distance travelled during the hand brake effectiveness test were not sufficient for all the slack to be compressed. That is why the LE had to push the cars another 9 feet in order to release the tension in the knuckles, so that the operating lever could be used to open the knuckle and separate the cut.

There is no specific rule on how much time must be allowed to elapse for slack in the train to adjust. Trains crews must rely on their knowledge, experience, and judgment when carrying out this task. Their actions and decisions are predicated on their understanding of the many interrelated factors involved in securing rail cars, including track configuration, environmental conditions, equipment tonnage, available slack based on car type, and slack action. In G Yard, the lead to track G05 (west of the west switch) is on level ground, while track G05 is on a descending grade. Consequently, during the hand brake effectiveness test, slack action timing varied on the 2 sections of the train, a fact that might not be considered by train crews, regardless of their experience.

The LER data indicated that the lead locomotive had reversed to a distance where the slack was partially compressed only on the first car with a hand brake applied (car 64). Although the force applied during the hand brake effectiveness test was not sufficient to fully compress all the slack, it was sufficient to cause a small adjustment on car 64. Since the other cars with applied hand brakes did not move, the conductor determined that the hand brakes were providing sufficient force.

After judging the hand brake effectiveness test to be successful, the crew proceeded to separate the cars. The conductor closed the angle cock between cars 63 and 64 and informed the LE that he had done so. Seventeen seconds after the movement came to a complete stop, the LE triggered the emergency feature on the end-of-train device. The emergency brake application immediately halted any further slack adjustment and provided an additional securing force to prevent the cars from moving.

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

The force applied by the locomotive to the movement during the hand brake effectiveness test and the time allowed for the cars to react were insufficient for the slack to fully adjust to the cars being cut off before the LE applied the independent brake. Consequently, the hand brake effectiveness test was incomplete and the crew were unaware that the number of hand brakes used to secure the cars was insufficient for the descending grade.

2.3 Securement practices of rolling stock in G Yard

Securing cars properly in G Yard is a complex task that requires a good grasp of slack action under various conditions, including tonnage and track grade; this can be a challenge even for trained and experienced crews.

At CP, requirements for securing rolling stock on non-main track are contained in the General Operating Instructions (GOI) and in location-specific operating bulletins as applicable. With respect to the number of hand brakes to be applied when securing equipment on non-main track, the GOI state that “two or more cars must be left with a sufficient number of hand brakes applied, at least one, unless a greater number is prescribed.”Footnote 32

Between 2008 and 2012, the practice was to apply a minimum of 5 hand brakes at both the east end and west end of the tracks. A change was made in about 2012 to apply a minimum of 5 hand brakes at only the east end (the bottom of the grade). This was again changed in about 2014 such that, at the time of the occurrence, hand brakes could be applied at either end of the train based on instructions from the west tower.

Operating instructions, such as those in the GOI and in the operating bulletins, indicate to crews what they must do in general. At the time of this report, none of these documents provided detailed guidance to employees on how to complete all phases of the required tasks, such as guidance on the potential differences in slack action when on various combinations of grades (i.e., level, ascending, and descending).

Finding as to causes and contributing factors

The impacts of slack action on various combinations of grades specific to G Yard during the hand brake effectiveness test were not addressed in CP’s instructions to crews and were not fully considered when testing was performed to verify the securement of the cars.

2.4 Safety management systems

Since 2010, the TSB Watchlist has emphasized the need for an operator’s safety management system (SMS) to be implemented effectively, to ensure that hazards are proactively identified and risks are mitigated.

Effective risk management does not completely eliminate risk. Rather, it manages risk to a level as low as reasonably practicable, as defined and communicated throughout the company and to stakeholders. Therefore, when the TSB identifies a hazard that likely contributed to an occurrence or risk of occurrence, it must consider whether the company’s SMS was applied and, if so, whether it was applied effectively.

In this occurrence, despite numerous changes to rolling stock securement practices in G Yard over the years, including changes to the number of hand brakes required to be applied, and at least 2 uncontrolled movements of significant blocks of cars resulting in derailments, CP could not provide any documentation stating that the changes had been analyzed in accordance with CP’s SMS. Specifically, the following were not performed: analyses to identify hazards associated with changes to the securing operations and the associated risk assessments, safety action plans, documentation, and verification of effectiveness. As such, no specific risk mitigation measures were established for the securement of rolling stock in G Yard.

Finding as to risk

If CP’s SMS is not engaged when a change to railway operations occurs, such as changes to car securement procedures, hazards may not be identified and their risks assessed and mitigated, increasing the risk of accidents.

3.0 Findings

3.1 Findings as to causes and contributing factors

These are conditions, acts or safety deficiencies that were found to have caused or contributed to this occurrence.

- The derailment occurred when a cut of 103 stationary cars, which had been secured for about 18 hours with 6 hand brakes and the emergency air brakes, ran uncontrolled down a 0.45% grade after the air brakes were released.

- The force applied by the locomotive to the movement during the hand brake effectiveness test and the time allowed for the cars to react were insufficient for the slack to fully adjust to the cars being cut off before the locomotive engineer applied the independent brake. Consequently, the hand brake effectiveness test was incomplete and the crew were unaware that the number of hand brakes used to secure the cars was insufficient for the descending grade.

- The impacts of slack action on various combinations of grades specific to G Yard during the hand brake effectiveness test were not addressed in Canadian Pacific Railway Company’s instructions to crews and were not fully considered when testing was performed to verify the securement of the cars.

3.2 Findings as to risk

These are conditions, unsafe acts or safety deficiencies that were found not to be a factor in this occurrence but could have adverse consequences in future occurrences.

- If Canadian Pacific Railway Company’s safety management system is not engaged when a change to railway operations occurs, such as changes to car securement procedures, hazards may not be identified and their risks assessed and mitigated, increasing the risk of accidents.

4.0 Safety action

4.1 Safety action taken

4.1.1 Transportation Safety Board of Canada

On 13 March 2023, the TSB issued Rail Transportation Safety Advisory Letter 03/23 “Switching and car securement practices at Canadian Pacific Railway Company’s Toronto Yard” to Transport Canada (TC).

The letter was issued as a result of 3 recent uncontrolled movements within G Yard of Canadian Pacific Railway Company’s (CP’s) Toronto Yard. It indicated that, in each of the uncontrolled movements, the securement of the cuts of cars was inadequate for the circumstances involved and resulted in the cars rolling uncontrolled and the leading cars derailing. In 2 of the 3 occurrences, the hand brake effectiveness test required by Canadian Rail Operating Rules (CROR) Rule 112(vi) was performed incorrectly.

The letter stated that TC might wish to audit CP’s switching and car securement practices for the yard to ensure that adequate procedures are in place to prevent uncontrolled movements.

4.1.2 Transport Canada

On 21 June 2023, TC replied to Rail Transportation Safety Advisory Letter 03/23 indicating that

[f]ollowing the three occurrences, TC conducted inspections and determined that all three uncontrolled movements were the result of non-compliance to CROR Rule 112. The inspection conducted following occurrence R22T0045 also resulted in Transport Canada issuing CP a Notice under Section 31 of the Railway Safety Act. The Notice was issued due to the railway’s “failure to implement effective measures to prevent the uncontrolled movement of equipment in CP’s Toronto Yard.”

The Notice prompted the company to take safety actions; subsequent TC inspections at the yard confirmed the implementation of the safety actions.

TC’s response further stated that, given TC’s commitment to reducing the number of uncontrolled movements of equipment during switching activities, TC planned, for 2023 to 2024, to conduct 8 crew performance inspections at CP’s Toronto Yard and 60 inspections focused specifically on switching/securement activities nationally.

In addition to these planned oversight activities, TC will continue to collect and analyze uncontrolled movement data to inform further oversight activities, including an audit, as appropriate.

4.1.3 Canadian Pacific

Immediately after this occurrence, CP performed simulations in Calgary, Alberta, that were followed with a risk assessment of car-securement procedures in G Yard based on rail-car tonnage and track gradient. The risk assessment established that additional hand brakes were required to adequately secure unattended cars throughout G Yard.

On 15 March 2022, CP performed hand brake effectiveness testing in G Yard to validate these simulations. The testing took into account train consists and weather variables, mathematical verification of the required number of hand brakes (based on brake force and rolling resistance industry calculations), and incorporation of wind effects into the hand brake modelling.

As a result, CP developed a new hand brake table to be used when securing unattended equipment in G Yard. CP accordingly issued Operating Bulletin SO-007-22Footnote 33 containing a new minimum hand brake chart for unattended cars in G Yard. In the new chart, the minimum number of hand brakes for a train with the same tonnage as the occurrence train is 10 hand brakes. The bulletin, which was communicated to all operating employees who worked in the Toronto Yard, also stipulated the following measures:

- a requirement to confirm slack relative to the applied hand brakes (bunched for rail cars secured at the east end and stretched for rail cars secured at the west end of G Yard) and to communicate that information to another crew member or qualified person(s); and

- a requirement for CP Mechanical employees to visually verify the number of hand brakes applied to the rail cars before bleeding the air from rail cars and to obtain confirmation from the appropriate supervisor that the minimum hand brake requirements comply with the chart for G Yard.

On 01 April 2022, CP issued a revision to Operating Bulletin SO-007-22, implementing the following changes to further address and mitigate the possibility of an uncontrolled movement in consideration of the grade at the east end of G Yard:

- Rail cars are not permitted to be left unattended and secured on the west end of the G Yard with hand brakes applied unless the movement, trains, or transfers are connected to a locomotive that

- is equipped with roll-away protection;

- is conditioned correctly for lead position and has had a brake test completed along with the rest of the cars in the train; and

- has distributed air throughout all rail cars included in the movement.

On 03 August 2023, CP issued Operating Bulletin SO-032-23, implementing the use of track skates as a physical defence against uncontrolled movements.

CP has also taken action to further educate employees on securement requirements at G Yard. Examples of specific actions include:

- A job aid provided to all employees that specifies the minimum brake requirements relative to the tonnage of the equipment in the track

- Training for new trainees that was focused directly on securement procedures.

- Safety blitzes:

- A safety blitz conducted from 13 to 26 December 2023 included a review of previous occurrences involving improper securement in Toronto Yard. As part of this safety action, 269 efficiency tests were conducted.

- A safety blitz conducted on 01 January 2024 included a review of procedures for securement of equipment, such as the application of hand brakes and the requirement for verbal confirmation between crew members.

- Efficiency testing: from 01 to 07 January 2024, the local team conducted 195 efficiency tests related to activities that can prevent or mitigate uncontrolled movements

Since this occurrence, local leaders are also performing daily validations of securement in Toronto Yard to identify non-compliance. The findings are discussed with other employees during pre-shift briefings.

This report concludes the Transportation Safety Board of Canada’s investigation into this occurrence. The Board authorized the release of this report on . It was officially released on .

Appendices

Appendix A – Selected train handling events

Table A1 lists selected train handling events in this occurrence, compiled from locomotive event recorder data, as well as calculated run-out distances covered by the train during the hand brake effectiveness test. The calculations took into account the variations in gradient east and west of the G05 switch and the available slack.

In Table A1,

- “EQR (psi)” refers to the pressure, in pounds per square inch, produced by the lead locomotive’s equalizing reservoir.

- “BPP (psi)” refers to the brake pipe pressure, in pounds per square inch, read on the lead locomotive.

- “EOT (psi)” refers to the pressure, in pounds per square inch, measured by the end-of-train device.

- “BCP (psi)” refers to the brake cylinder pressure on the lead locomotive, in pounds per square inch.

| Time (EST) | Speed (mph) | Throttle position | EQR (psi) | BPP (psi) | EOT (psi) | BCP (psi) | Event |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1812:48 | 4.6 | Idle | 89 | 89 | 83 | 0 | The train is slowly pulling westward on track G05 of Toronto Yard after having entered the yard from the north main track at Mile 196.7 of the Belleville Subdivision. |

| 1812:50 | 4.2 | Idle | 82 | 85 and decreasing | 83 | 0 | The locomotive engineer (LE) makes a minimum brake application. |

| 1812:55 | 3.9 | 1 | 82 | 82 | 83 | 0 | With the minimum brake application in effect, the LE starts to throttle up. |

| 1813:12 | 2.8 | 2 | 82 | 81 | 77 | 0 | The brake pipe pressure between the head end and the end-of-train device stabilizes. |

| 1813:30 | 2.5 | 4 | 82 | 81 | 77 | 0 | The LE puts the throttle in position 4 (the maximum throttle position used with the minimum brake application in effect). |

| 1813:51 | 2.8 | 3 | 82 | 81 | 77 | 0 | The LE starts to reduce the throttle to stop the train. |

| 1814:03 | 2.1 | Idle | 82 | 81 | 77 | 0 | The throttle is down to idle. |

| 1814:18 | 0 | Idle | 82 | 81 | 77 | 0 | The train comes to a stop after travelling 312 feet with a minimum brake application. |

| 1814:19 | 0 | Idle | 82 | 81 | 77 | 3 and increasing | The LE starts to apply the independent brake on the locomotives. |

| 1814:23 | 0 | Idle | 82 | 81 | 77 | 71 | The maximum independent brake force is obtained. |

| 1814:26 | 0 | Idle | 80 | 80 and decreasing | 77 | 71 | The LE makes a further brake pipe pressure reduction of 2 psi. |

| 1814:31 | 0 | Idle | 80 | 79 | 77 | 71 | The brake pipe pressure stabilizes; no change in end-of-train pressure. |

| 1814:37 | 0 | Idle | 81 and increasing | 79 | 77 | 71 | The LE releases the automatic brake while the conductor is applying hand brakes. |

| 1818:18 | 0 | Idle | 89 | 89 | 80 | 71 | The maximum pressures are reached. |

| 1818:19 | 0 | 1 | 89 | 89 | 80 | 69 and decreasing | The LE begins the hand brake effectiveness test by releasing the independent brake and moving the throttle to position 1 in reverse. |

| 1818:26 | 0.4 | 1 | 89 | 89 | 80 | 3 | The movement begins reversing. |

| 1818:29 | 0.4 | 1 | 89 | 89 | 80 | 0 | The independent brake is fully released. |

| 1818:43 | 1.1 | Idle | 89 | 89 | 80 | 0 | The LE prepares to stop the movement by placing the throttle to idle. |

| 1818:44 | 1.1 | Idle | 89 | 88 | 80 | 2 and increasing | While the movement is still in motion, the LE starts to apply the independent brake. The lead locomotive has covered a distance of 16.5 feet. |

| 1818:46 | 0.7 | Idle | 89 | 88 | 80 | 52 | The maximum independent brake pressure reaches 52 psi. |

| 1818:47 | 0 | Idle | 89 | 88 | 80 | 44 | The lead locomotive comes to a temporary stop after having covered an additional 4.2 feet; the independent brake pressure is 44 psi. |

| 1818:48 | 0.4 | Idle | 89 | 88 | 80 | 26 | The slack runs out on the head end, which causes a brief surge in speed and the movement covers 1 more foot. |

| 1818:50 | 0 | Idle | 89 | 88 | 80 | 39 and increasing | The lead locomotive comes to a complete stop. The total distance covered during the hand brake effectiveness test is 21.7 feet. |

| 1818:56 | 0 | Idle | 89 | 88 | 80 | 71 | The maximum independent brake pressure reaches 71 psi. |

| 1819:07 | 0 | Idle | 89 | 88 | 0 | 71 | The LE, after being informed by the conductor that the hand brake effectiveness test was successful and that he had closed the angle cock between cars in positions 63 and 64, triggers the end-of-train device. |

| 1819:24 | 0.4 | 1 | 89 | 89 | 0 | 4 and decreasing | The LE, after being asked by the conductor for more slack in order for him to operate the uncoupling lever of the coupler and open one of the knuckles to separate the cars in positions 63 and 64, starts to make a reverse move to provide the requested slack. |

| 1819:37 | 0 | Idle | 89 | 89 | 0 | 65 | The lead locomotive stops after moving about 9 feet. |

| 1819:50 | 0.4 | 2 | 89 | 89 | 0 | 2 and decreasing | The lead locomotive proceeds forward to double over into track G03. |

Appendix B – TSB investigations involving uncontrolled movements

| No. | Occurrence number | Date | Description | Location | Cause |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | R20V0230 | 2020-11-13 | Uncontrolled movement of rolling stock, Canadian National Railway Company (CN), remote control locomotive system (RCLS), yard assignment 1500 North end, Mile 462.4, Chetwynd Subdivision | Prince George, British Columbia | Loss of control |

| 2 | R19C0015 | 2019-02-04 | Uncontrolled movement of rolling stock and main-track train derailment, Canadian Pacific Railway Company (CP), freight train 301-349, Mile 130.6, Laggan Subdivision | Yoho, British Columbia | Loss of control |

| 3 | R18Q0046 | 2018-05-01 | Uncontrolled movement and derailment of rolling stock on non-main track, Quebec North Shore and Labrador Railway (QNS&L), cut of cars, Sept-Îles Yard | Sept-Îles, Quebec | Switching |

| 4 | R18M0037 | 2018-12-04 | Uncontrolled movement of rolling stock and employee fatality, CN yard assignment L57211-04, Mile 1.03, Pelletier Subdivision | Edmundston, New Brunswick | Securement |

| 5 | R18H0039 | 2018-04-14 | Uncontrolled movement of rolling stock, CP RCLS, yard assignment T16-13, Mile 195.5, Belleville Subdivision | Toronto, Ontario | Loss of control |

| 6 | R18E0007 | 2018-01-10 | Uncontrolled movement of rolling stock, CN freight train L76951-10, Mile 0.5, Luscar Industrial Spur | Leyland, Alberta | Loss of control |

| 7 | R17W0267 | 2017-12-22 | Uncontrolled movement and employee fatality, CN RCLS, extra yard assignment Y1XS-01, Melville Yard | Melville, Saskatchewan | Switching |

| 8 | R17V0096 | 2017-04-20 | Non-main track uncontrolled movement, collision, and derailment, Englewood Railway, Western Forest Products Inc., cut of cars | Woss, British Columbia | Switching |

| 9 | R17Q0061 | 2017-07-25 | Uncontrolled movement, QNS&L train PH651, Mile 128.6, Wacouna Subdivision | Mai, Quebec | Securement |

| 10 | R16W0242 | 2016-11-29 | Uncontrolled movement, collision, and derailment, CP ballast train BAL-27 and freight train 293-28, Mile 138.70, Weyburn Subdivision | Estevan, Saskatchewan | Loss of control |

| 11 | R16T0111 | 2016-06-17 | Uncontrolled movement of railway equipment, CN RCLS 2100 west industrial yard assignment, Mile 23.9, York Subdivision, MacMillan Yard | Vaughan, Ontario | Loss of control |

| 12 | R16W0074 | 2016-03-27 | Uncontrolled movement of railway equipment, CP 2300 RCLS training yard assignment, Mile 109.7, Sutherland Subdivision | Saskatoon, Saskatchewan | Switching |

| 13 | R16W0059 | 2016-03-01 | Uncontrolled movement of railway equipment, Cando Rail Services, 2200 Co-op Refinery Complex assignment, Mile 91.10, Quappelle Subdivision | Regina, Saskatchewan | Securement |

| 14 | R15D0103 | 2015-10-29 | Runaway and derailment of cars on non-main track, CP, stored cut of cars, Mile 2.24, Outremont Spur | Montréal, Quebec | Securement |

| 15 | R15T0173 | 2015-07-29 | Non-main-track runaway, collision, and derailment, CN, cut of cars and train A42241-29, Mile 0.0, Halton Subdivision | Concord, Ontario | Switching |

| 16 | R13D0054 | 2013-07-06 | Runaway and main-track derailment, Montreal, Maine & Atlantic Railway, freight train MMA-002, Mile 0.23, Sherbrooke Subdivision | Lac-Mégantic, Quebec | Securement |

| 17 | R12E0004 | 2012-01-18 | Main-track collision, CN, runaway rolling stock and train A45951-16, Mile 44.5, Grande Cache Subdivision | Hanlon, Alberta | Securement |